- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Water Resources and Agricultural Development in the Tropics

About this book

First published in 1988. There are many excellent texts on water supply and irrigation engineering, irrigation economics, agricultural development and the problems which often plague such efforts. Few syntheses of such writings have been made, despite a clear need for them from people interested in water resources and agricultural development: students of geography, economics, development studies and agricultural management, administrators, planners and aid agency staff. This book attempts to provide a broad interdisciplinary introduction for such people.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Water Resources and Agricultural Development in the Tropics by Christopher J. Barrow in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Human Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

WATER RESOURCES AND AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT: BACKGROUND AND PRINCIPLES

Chapter 1

Factors affecting tropical agricultural development

Introduction

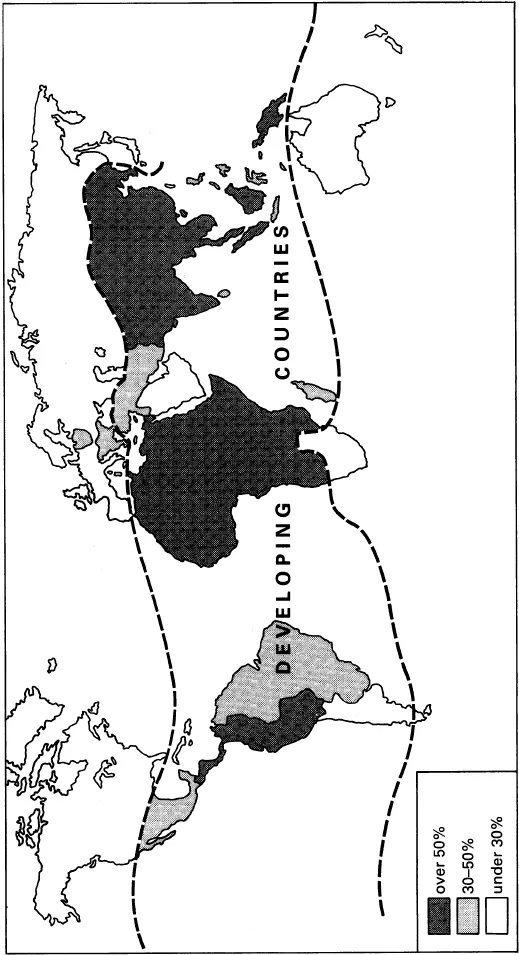

Roughly three-quarters of the world’s population live in some 160 countries collectively referred to as the South, the Third World, less-developed countries, underdeveloped or developing countries. About two-thirds of the total population of these countries depend directly or indirectly upon agriculture for livelihood, often merely to subsist, sometimes barely to survive (Fig. 1.1) (OECD 1982: 11; World Bank 1982: 39).

Agricultural development, although still concerned with the opening-up of virgin land in a few countries, more often involves the improvement and, increasingly, the rehabilitation of existing traditional agriculture and sometimes of failed development efforts. Traditional agricultural strategies are deteriorating in many regions as a result of a range of ‘development pressures’, some generated within developing countries, some from outside. These include population growth, the adoption of inappropriate agricultural strategies and/or unsuitable techniques, new tastes or attitudes, or the failure to modify outmoded, harmful local ways (Mabogunje 1980; Todaro 1981: 50–80; Dickenson et al. 1983).

The degeneration of agricultural systems, whether traditional or recently introduced, has frequently caused serious environmental and socio-economic impacts. From the early 1970s ecologists and environmentalists studying development-related problems in the tropics have called for ‘ecodevelopment’, that is, environmentally informed development (Dasmann et al. 1973; Eckholm 1976; Ehrlich et al. 1977; Glaeser 1984). Realization that difficulties exist comes much swifter than the information, expertise, trained personnel, funding and changes in people’s attitudes that are needed to avoid or mitigate such problems (Independent Commission on International Development Issues 1980: 20, 47; IUCN, UNEP, and WWF 1980; Brandt Commission 1983). The environmental degradation in developing countries so clearly linked with agricultural production has become so obvious that many writers refer to the ‘South’s environmental crisis’ (Riddell 1981; Redclift (1984). Combatting environmental deterioration and improving agricultural production are very important closely related issues and often a key factor in achieving either is sound water resources management.

Fig. 1.1 The Developing Countries – Difine By The Approximate Percentage Of People in Agriculture Employement

Source: Price G (1983) Patterns of Development: Population and Food Resources in the Developing World, Edward Arnold, London, p. 9 (Fig. 9).

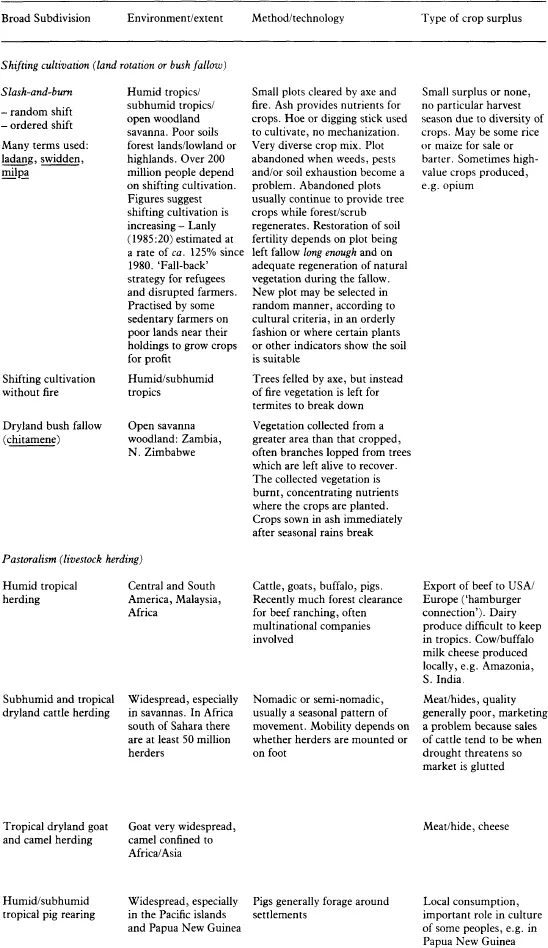

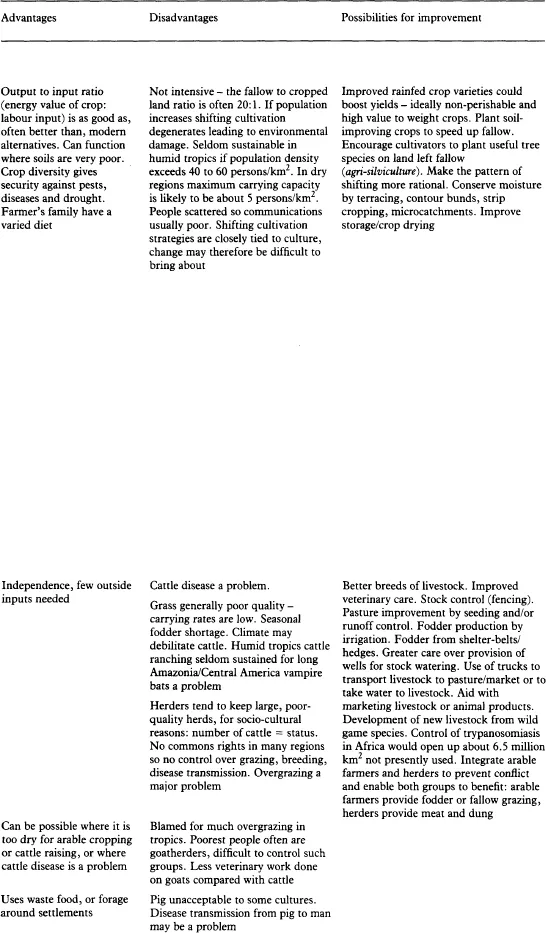

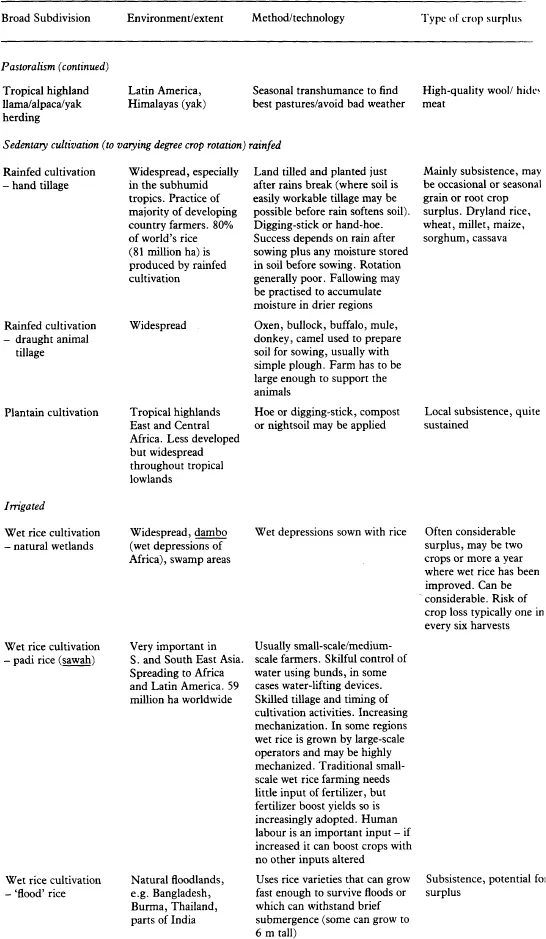

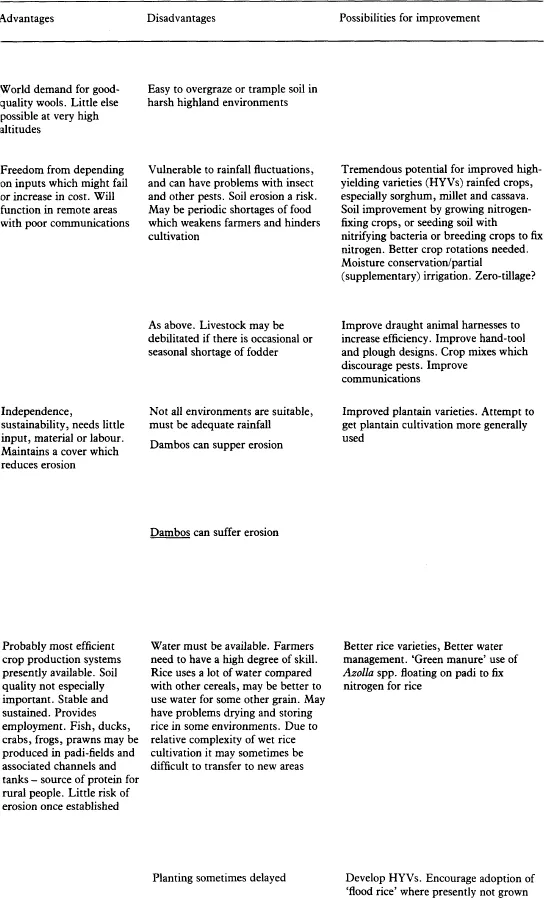

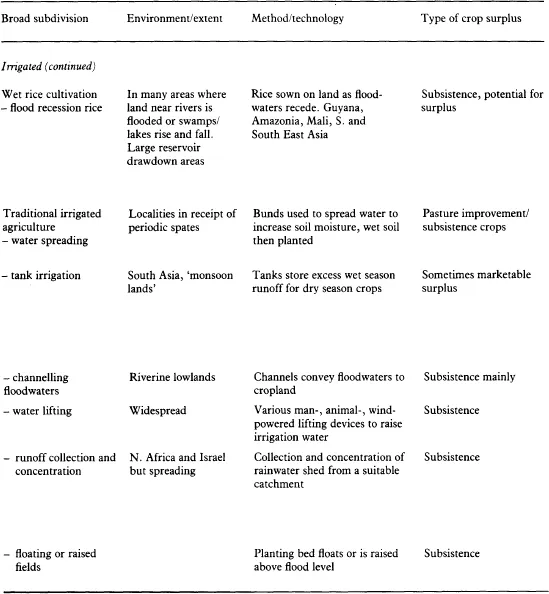

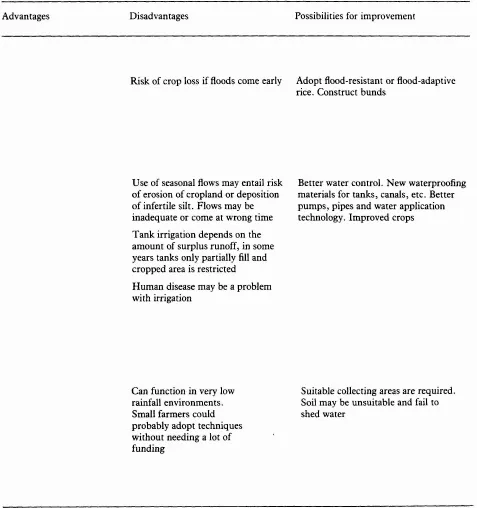

Although there may be broad similarities between developing countries, there are nevertheless tremendous differences in environmental conditions and agricultural practices from locality to locality (Golley & Medina 1975). Traditional agricultural systems in the tropics are outlined in Table 1.1.

Socio-economic and socio-political factors affecting tropical agriculture

Traditional farmers and herders

Although well over half the population of developing countries depends upon small-scale, mainly subsistence agriculture, until relatively recently investors, researchers and planners paid pitifully little attention to this sector. In contrast massive investment, research and development support has been given to large-scale, mainly commercial production by state-run agricultural organizations or multinational corporations of crops for export or to feed urban populations. Also, a disproportionate amount of research has been done to improve commercial crops like: rubber or coffee. Much less has been done to improve subsistence crops and the farming methods of small-scale producers (Richards 1985: 19).

The dramatic gains in agricultural production which should be possible when large-scale irrigation schemes are established has led the governments of many developing countries and funding agencies to favour this form of development. Unfortunately the employment opportunities and profits (if any) generated by such developments frequently do little to help those who practise small-scale rainfed cultivation, small-scale irrigation or pastoralism, often in relatively remote locations (the majority of farmers in developing countries) (Redclift 1984: 31). Some countries which invested in large-scale, often irrigated, production of export crops like cotton have seen their returns cut by falling world market prices beyond their control and have found it difficult to pay for agricultural infrastructure, the inputs it requires and other necessary imports.

Although highly variable, available figures show that small farmers work about 40 per cent of the world’s total cultivated land, some practising shifting cultivation, and some sedentary farming (Arnon 1981: 1). Few small farmers own their land; most are tenants who sometimes pay exorbitant rents, or are sharecroppers or even serfs bound to feudal masters, and in some countries farmers work land which is communally owned. Such farmers have little incentive to invest effort or money in improving production for fear it may benefit others rather than themselves or their families (George 1977: 34; Redclift 1984: 33).

Table 1.1 Traditional agricultural systems

Sources:

Shifting cultivation: Nye & Greenland 1960; Conklin 1961; Allan 1965, Spencer 1966; Janzen 1973; Grandstaff 1978; 1981; Hunter & Kwakuntiri 1978; Ruthenberg 1980; Rambo 1982; Lanly 1985.

Pastoralism: Johnson 1969; Box 1971; Swift 1977a; McCown et al. 1979; Walker 1979; Shaffer 1980; Heathcote 1983; Manassah & Briskey 1981; von Maydell & Spatz 1981; Sandford 1983. Sedentary Cultivation: Bayliss-Smith, 1982; Grist 1959; Geertz 1963; Grigg 1970; Gourou 1980; Spencer 1974, Fernando 1980a; Wrigley 1981; Byres et al. 1983; Swaminathan 1984.

Most developing country farmers work plots of less than 5 ha and many cultivate less than 2 ha. Given irrigation. and good soil, 1 ha in the tropics could support a typical smallholder family. However, circumstances are seldom that favourable and a 1 or even a 2 ha plot under rainfed cultivation is likely to provide a livelihood well below the World Bank absolute poverty line (meaning an existence somewhere between a barely adequate diet and starvation). While small farmers frequently have miserable life-styles, there are some who are even less fortunate – the landless agricultural labourers who comprise as much as one-third of the rural population in some regions. Although not necessarily precluding agricultural improvement, small farm size usually means the farmer is poor and poverty is a major retardant on development (Schultz 1964: 105).

The small farmer’s predicament is difficult not only because he/she is poor and lacks secure access to sufficient land, but because the people who control financial aid, pass legislation, administer taxation, decide agricultural research priorities and who control the national market prices for farm produce, indeed those who determine almost everything that can help or hinder small farmers, are likely to be based in cities and seldom have an adequate understanding of the problems faced by rural people; they may regard them as ‘backward’ and ‘inefficient’ (Lipton 1977; Harriss 1982: 94). It is not unusual for farm prices to be held artificially low, exacerbating rural poverty in order to ensure cheap food supplies so as to avoid unrest in cities and demands for increased wages in industry. Without equitable domestic terms of trade there will be little reinvestment in small-scale agriculture and through that long-term development (Bunting 1970). Unfortunately, when developing country decision-makers do show concern for rural peoples they often do so because of tribal or kinship ties or political motives, rather than true concern for the well-being of countryfolk (Falkenmark & Lindh 1976: 177; Todaro 1981: 482).

Expatriate or expatriate-trained personnel concerned with agricultural development have commonly associated ordered, neat planting with good husbandry, even where such practices are inappropriate. Small farmers with irregularly spaced crops, who are reluctant to waste effort on non-essential activity get dismissed as ‘lazy’. Generations of experience have been accumulated by small farmers and herders, but it is passed on by word of mouth and often missed by those setting out to develop tropical agriculture. This experience is, according to Richards (1985: 40): ‘… the single largest knowledge resource not yet mobilized in the development enterprise.’

It is true that those practising traditional agriculture are sometimes slow to adopt new ways, but this may often be because they have little or nothing with which to pay for inputs. They have no security against failed experimentation, and advice is seldom available to them. Sometimes it may be to the advantage of the traditional farmer to keep a ‘low profile’ because the image of a ‘subsistence backwater’ is ‘… as good as any to fend off the tax gatherer and others interested in taking a share of what may be a thriving trade in basic foodstuffs’ (Richards 1985: 111).

Given adequate support, new crops and techniques which are seen to work and which are affordable are usually adopted sooner or later. Indeed, in Africa, and very likely elsewhere, traditional farmers have a history of inventive self-reliance. Nevertheless, there are practices and attitudes which hinder development, and there may be no relatively fast ‘technological fix’ for these. For example some peoples scorn arable cultivation. Taboos and tastes may preclude the raising of otherwise suitable crops or livestock. The importance of women in traditional agriculture has been neglected by those charged with developing agriculture. The Independent Commission on International Development Issues (1980: 60) noted that: ‘Africa’s food producers – the women–continue largely to be ignored.’ Agricultural funding or education directed towards menfolk can therefore be largely wasted.

The attraction of wage labour in mines or cities can deplete rural areas of their strongest, most able males, leaving a less dynamic, often elderly and conservative workforce which hinders any development of agriculture. The replacement of a subsistence economy with a cash economy is fraught with danger, for those with little experience of handling money can easily get into debt and lose their crops or land.

Population increase and the breakdown of traditional agricultural practices

In many developing countries population growth is such that increases in food production have little impact on per capita food consumption. In some regions population growth is doing far more damage by causing the degeneration of traditional agriculture. The problem is particularly marked in tropical drylands where recent estimates suggest population rose by roughly two-thirds between 1960 and 1974 (Harris 1980: vi).

Once-stable crop and livestock production systems break down when a population increases enough to cause a reduction of fallow periods or overstocking. Land rotation farming systems (shifting cultivation) and pastoralism are especially vulnerable and their vulnerability increases where soils are poor and/or there are periods with so little rainfall that vegetation is under stress. Once degeneration starts things tend to go from bad to worse; poor yields from the land means that it is put under further pressure and so suffers more. The incidence of poverty, malnutrition and poor health increases; people’s morale deteriorates – and in a short time they can do little to rehabilitate the land and boost agricultural output unaided. This scenario may be found in large parts of Bangladesh, Thailand, Vietnam, North-East Brazil, Malagasy, South Yemen and Bolivia; but in Africa the situation seems especially desperate. Clearly there are tremendous difficulties in the Sahel, the Sudan and Ethiopia, but much greater parts of the continent seem destined to join the suffering. According to Higgins et al. (1981), all parts of Africa with less than a 149–day growing season were already carrying over twice the population that can be sustained with the techniques and inputs traditionally used (Table 1.2; Fig. 1.2). More recent studies reinforce these warnings (...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Part I WATER RESOURCES AND AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT: BACKGROUND AND PRINCIPLES

- Part II WATER RESOURCES AND AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT: TECHNOLOGY AND PRACTICE

- References

- Index