- 344 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Vegetation and Soils is an introduction to the study of vegetation and soil distribution. In this accessible work, S. R. Eyre describes the distributions of these two important elements in the landscape. The book progresses regionally, and the land areas of the earth are subdivided according to the distribution of their main vegetation and soil types. The author argues that the nature of the soil is not determined by vegetation any more than it is determined by climate, but the nature of the vegetation always has some bearing on the nature of the soil, and vice versa.Eyre studies the ways in which plant communities and soil profiles develop and the complexity of the vegetation-climatic relationship. The middle and high latitudes are examined, as well as the tropical regions. In order to avoid broad generalizations of vast regions, the example of the British Isles is used to show that vegetation and soil maps can be misleading on a continental scale. The book concludes with a series of vegetation maps, which show the distribution of plant formations. Also included are tables providing climatic correlations with vegetation and a glossary of relevant terms.This classic work shows the intimate connection between vegetation development and soil development. For this reason, this book is a major contribution to the study of the physical aspects of geography and will be of particular interest to students of geography, botany, and agriculture.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Vegetation and Soils by S. R. Eyre in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

VEGETATION AND SOIL DEVELOPMENT

CHAPTER I

The Original Landscape and the Hand of Man

IN the first chapter of the Book of Genesis one may read how the dry land emerged from the oceans and became populated with plants and animals and how, ultimately, man appeared on the scene to use the landscape for his own purposes. Although it has now been demonstrated that all this did not take place within the space of a mere seven days, it is clear that the ancients of Babylonia had a clear and almost inspired vision of the general order of world evolution. As the initially hot earth cooled down, one of the gases in its atmospheric envelope began to condense and liquid water accumulated on the lower portions of the surface of the globe; the higher portions remained above water-level. The oceans and continents thus came into existence. The remaining atmosphere continued to circulate around the earth, abstracting water from the oceans and depositing it on the continents as rain. The sun shone between the rains and warmed the land surfaces. In this warm, moist and relatively stable environment, terrestrial plants and animals evolved and multiplied. The plants rooted themselves firmly in the weathered surface of the land and their dead remains supplied it with organic material. True soils thus came into existence.

Because of mountain-building, erosion, sedimentation and other geomorphological processes, the land surfaces increased in complexity. A great variety of rocks made their appearance and the soils which developed in their weathering residues were very different. Mountain ranges formed climatic divides and precipitation and temperature varied greatly from one place to another. In consequence the vegetation of the earth, so dependent upon soil, rainfall and sunshine, evolved very differently in different regions. In turn, the various species of animal, dependent upon different plants for shelter and food, accommodated themselves to this varied vegetation pattern.

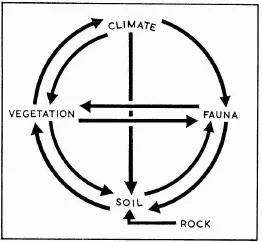

The original untamed landscape thus varied enormously from place to place. Everywhere however it was compounded of the same interdependent components (Fig. 1). Climate exercises a very strict and sometimes direct control on the development and distribution of plants, animals and soils; all species have a specific range of moisture and heat requirements and the rates of weathering, organic decay and leaching in soils are strongly influenced by the same climatic elements. On the other hand, climate itself is profoundly affected by the nature of the vegetation cover; wind speed, temperature regime and atmospheric humidity just above the surface of the ground beneath the shade of dense forest, are remarkably different from those at just the same height above soil level in near-by grassland. Vegetation controls the distribution of animals most rigorously; each animal must remain within reach of the plants upon which it feeds or, in the case of a carnivore, within reach of its prey which, in turn, is controlled in its distribution by vegetation. Conversely, the fauna exerts some effect on vegetation. Large herds of wild ungulates, because of their selective grazing, must favour some plants at the expense of others. Similarly there are reciprocal relationships between soil and vegetation and between soil and fauna.

Fig. 1. The ecosystem or biotic complex.

This complex of interacting phenomena has frequently been referred to as the ‘biotic complex’ or ‘ecosystem’. Any change affecting any single element within it must obviously have repercussions throughout the entire system. For hundreds of millions of years all such changes were due entirely to the operation of the ‘blind forces of nature’; changes in climate occurred from time to time while, now and then, plant and animal evolution produced new species which fundamentally altered the structure and general appearance of the whole complex.

It was into this wild complex that modern man (Homo sapiens) intruded only a relatively short time ago. ‘The Garden of Eden’ awaiting him was thus a good deal wilder and more intransigent than the Scriptures imply. Man wandered in it for a long time with no thought of cultivation; he merely gathered fruits, leaves and roots, and preyed upon other animals. He thus modified his environment but little, probably affecting soil and vegetation no more than many other species of animal. Because of his potentialities for reasoning and intellectual development, however, Homo sapiens gradually changed his habits and increased his power over the other denizens of the primeval environment and over the forest habitat itself.

Ultimately, as his numbers increased and his technical skill became greater, man was able to sweep away much of the wild vegetation. In its place he planted orderly patches of those species which he had come to esteem most highly as food. More than that, he also changed the vegetation over even vaster areas by spreading fires and by pasturing those few species of grazing animal which he had domesticated. Only those plant species which could withstand firing and grazing were able to survive in these pastures. Directly and indirectly man also transformed the soil as well as the vegetation; he plied his spade and his plough in order to plant crops, thus destroying many of the natural features of the soil at one fell swoop. Furthermore, by gradually altering the vegetation on the grazing lands, he automatically, but more gradually, changed the soil over these wider areas.

During the very latest stage of his social evolution, man has wrought even more drastic changes in his environment. Over large areas, not only has the vegetation been almost completely eliminated, the soil also has disappeared beneath a veneer of asphalt, concrete, brick and tile. Here, the descendants of the hunters and gatherers of the primeval forest have continued to develop their skills as thinkers and toolmakers. In their millions they now pass their working days as mechanics, clerks and teachers, the majority of which never have occasion to think about the natural complex in which mankind evolved. On the other hand, many further millions are still engaged in using what remains of the original natural environment as the sole source of food and clothing for the whole of our species.

It is obvious that the evolution of human societies and the evolution of vegetation and soil over the past few thousand years must have been closely inter-related in many areas. The present landscape can be regarded as the product of two sets of forces; on the one hand there are the natural physical and biotic processes1 and, on the other, the activities of human communities. One of the most rewarding approaches to geography is to view it as the study of the ways in which the present landscape has been produced by the interaction between these two sets of forces. Unfortunately the nature of the interaction has frequently been gravely oversimplified; it has too often been assumed that the physical aspects of geography can be regarded as an almost static framework within which the human drama has been enacted. This has led to many misconceptions. The point has already been made that, quite apart from the effects of changes in the macroclimate, man’s removal or modification of the original vegetation must have affected all the other elements in the biotic complex. Soil, microclimate and water-availability have all been modified enormously; even the relief of the surface has sometimes been significantly changed by accelerated soil erosion. One should therefore never assume that the natural attributes of the landscape are just the same today as they were before man’s intervention; they may have changed out of all recognition. If one seeks to interpret the distribution of long-established human settlement in terms of the physical potentialities of the environment, the task is therefore far from easy. It is first necessary to reconstruct an image of the physical basis as it was at the time of the founding of the settlement. In subsequent chapters some attempt has been made to effect this reconstruction for those parts of the earth’s surface where human interference has occurred

Note

1 The biotic complex with its geological foundations has often been referred to as ‘the physical basis of geography’.

CHAPTER II

Vegetation Development

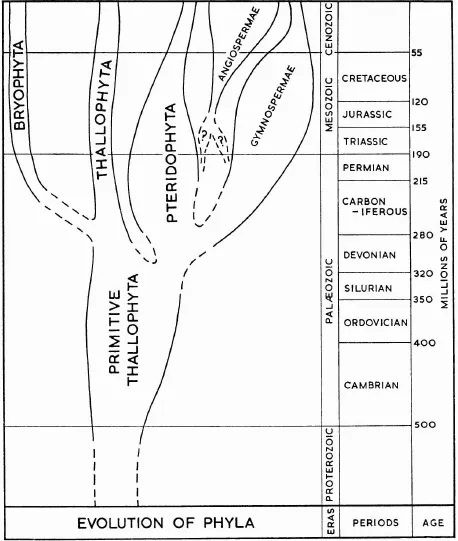

IT is probably some 400 or 500 million years since the ancestors of all the land plants which now inhabit the earth emerged from the oceans. They must have evolved from simple marine organisms similar in some ways to some of the present-day Algae. Before this time, for many hundreds of millions of years, plant-life must have been evolving, but it had probably been almost exclusively marine. The direct ancestors of all the most primitive classes of plants—the Algae, Fungi and Bacteria—probably evolved in the primeval oceans. These relatively simple plants are usually grouped together as one major phylum of the plant kingdom known as the Thallophyta. It seems likely that some primitive Algae invaded the land some time during the Cambrian or Ordovician Periods and that from them evolved the original ancestors of all the ferns, horsetails and club-mosses (Fig. 2). These more complex, spore-bearing plants, known collectively as the Pteridophyta, gradually gained ascendancy until they dominated the vegetation of all the land areas. By the end of the Carboniferous Period great forests of tree ferns, giant horsetails and tall club-mosses covered vast areas (Plate Ia). The coal seams of Carboniferous age are composed almost entirely of their remains. Some time during the Palaeozoic Era the original ancestors of all the mosses and liverworts—the Bryophyta—must also have sprung independently from thallophytic stock but the time and mode of their doing so is still quite obscure. Fossil remains of the Bryophyta are rare but sufficient have been found to show that both mosses and liverworts were in existence before the end of Carboniferous times. Unlike the pteridophytes, however, these plants appear never to have been important in the gross structure of most of the vegetation communities of the earth.

Even during the period of pteridophyte supremacy seed-bearing plants had already come into existence [58]. Seed-bearing plants as a whole are of two distinct types, the more primitive of which are called the Gymnospermae and the more advanced, the Angiospermae. The only large surviving group of gymnosperms today are the conifers (Coniferales). Conifers had made their appearance before the end of Carboniferous times and, although they must have originated in some way from pteridophyte stock, fossil evidence of their early evolution is incomplete. They remained quantitatively unimportant until the end of the Palaeozoic Era but, along with other primitive seed-bearing plants [58] they gained predominance over the woody pteridophytes with almost startling rapidity at the beginning of Mesozoic times, about 180 million years ago. They maintained this predominance throughout Triassic and Jurassic times (Plate Ib). Some time during early Mesozoic or even late Palaeozoic times however, the angios- permae made their appearance. It is by no means a foregone conclusion that they evolved from gymnosperm stock; they may have arisen quite independently from one of the pteridophyte groups. During the Cretaceous Period the angiosperms rapidly gained ground, mainly at the expense of the gymnosperms, until, by Eocene times, the former had become the predominant group of land plants. Some genera of conifers have remained important however.

Fig. 2. Evolution of the plant kingdom.

Angiosperm and coniferous trees similar to or almost identical with those which now dominate the earth’s vegetation have thus maintained their supremacy for 50 or 60 million years. Evolution, once started, has never stopped but it is clear that communities of plants can persist for millions of years with only slight changes in their floristic composition; as old individuals die they tend to be replaced by young ones of the same species so that changes in the composition of the community as a whole are negligible. From time to time species have become extinct and new ones have made their appearance but a significant percentage of the tree species which are common in our forests today are plentifully represented by almost identical ones in the fossil floras of the Cainozoic Era. Thus the thick beds of Miocene lignite near Cologne in Germany are found to be composed in very great part of the remains of cedars and redwoods (Sequoia spp.) which appear to have been identical with those still living in California.

Provided no catastrophic environmental change takes place, the vegetation of a particular area may therefore remain of almost constant composition over unimaginably long periods of time. Only occurrences like climatic changes and volcanic eruptions will cause wholesale changes in vegetation, some permanent and some only temporary. Nevertheless, every single square yard of the present land areas of the earth was, at one time, fresh and untenanted. All land areas began as upraised sea floors, lava flows, silted lake basins, abandoned ice-fields and the like. In some cases it is millions of years since the original invasion by vegetation took place, in others this occurred relatively recently. Not many thousands of years ago the whole of north-western Europe was covered by an ice cap which had advanced from the north and swept away almost every vestige of the former vegetation and soil. When the ice again retreated it left a completely inorganic surface—partly bare rock, partly smooth boulder clay plains and partly uneven surfaces of moraine or fluvio-glacial sand and gravel. The whole natural drainage system had also been disrupted by glaciation so that much of the area was ill-drained and studded with lakes. The whole of the present vegetation of north-western Europe is therefore of recent provenance having only just established itself on this relatively new surface. On the other hand vast areas of tropical rain forest in the Congo and Amazon basins have occupied their present positions for millions of years without interruption.

When a new surface is exposed it has no soil upon it and yet, when we examine the vegetation existing on the earth today, we discover that most types—forest, grassland and scrub—are rooted in quite a deep and complex soil. Furthermore, particular classes of vegetation seem to be associated with certain types of soil and vice versa. It is difficult to see how a dense forest could establish itself on a bare rocky surface and, on the other hand, how a brown forest soil could come into existence if the forest did not precede it. The dilemma is similar to the familiar one concerning the chicken and the egg and the answer even more complicated. In fact, within an area where the climate is quite suitable for the existence of a particular type of forest with its characteristic associated soils, neither the forest nor the soil will appear immediately upon a fres...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- PREFACE

- PART I. VEGETATION AND SOIL DEVELOPMENT

- PART II VEGETATION AND SOILS OUTSIDE THE TROPICS

- PART III. THE BRITISH ISLES

- PART IV. TROPICAL REGIONS

- CONCLUSION

- APPENDIX I. VEGETATION MAPS OF THE CONTINENTS

- APPENDIX II. CLIMATIC CORRELATIONS WITH VEGETATION

- APPENDIX III. GLOSSARY OF TECHNICAL TERMS

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX