- 182 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Perspectives On Psychology

About this book

This is a title in the modular "Principles in Psychology Series", designed for A-level and other introductory courses, aiming to provide students embarking on psychology courses with the necessary background and context. One aspect of this is to consider contemporary psychology in the light of its historical development. Another aspect is to examine some of the major controversies which have dominated psychology over the centuries. Yet another aspect is to consider some of the major areas of psychology eg social, developmental, cognitive in terms of what they have to offer in the quest for an understanding of human behaviour.; The book also addresses key issues which need to be considered as psychology matures into a fully fledged experimental and scientific discipline. For example, how much do laboratory experiments tell us about how people behave in the real world? And how far is it ethically permissable for psychologists to go in their pursuit of knowledge?

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Perspectives On Psychology by Michael W. Eysenck in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Cognitive Psychology & Cognition. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

What is psychology?

A useful starting point for this book is to consider what is meant by psychology. Most people have some idea what psychology is about, but they are often confused by the distinction between psychology and psychiatry. In fact, it is easier to define "psychiatry" than "psychology": psychiatry is concerned with the study and treatment of mental disorders, and psychiatrists have medical degrees. The definition of psychology has changed over the centuries, so it will be useful to adopt a historical approach.

The background

The word "psychology" means different things to different people. It derives from the Greek words psyche, meaning mind or soul, and logos, meaning study. Therefore, at least at one time, psychology was regarded as the study of the mind.

For many centuries it was generally believed that human beings had minds, but no other species did. As a consequence, psychology was almost entirely concerned with the study of the human mind. The easiest and most obvious way of investigating the human mind is by means of introspection (defined in the Oxford English Dictionary as "examination or observation of one's own mental processes"), and we shall be looking at this in Chapter 3.

The greatest challenge to the view that psychology is the study of the mind came from Charles Darwin in the nineteenth century, with his theory of evolution (see Chapter 2). If the human species has evolved from other species, it is a little difficult (although not impossible) to see how we could have minds when these other species do not. So, as psychologists reacted to the Darwinian revolution, their views of the nature of psychology began to change.

In the early twentieth century, the behaviourists in America argued that neither humans nor any other species possessed minds. This argument obviously makes sense if we have evolved from species that don't have minds. However, if minds don't exist, this poses some problems for the

notion that psychology is the study of the mind! Instead, the behaviourists argued, psychology is (or should be) the science of behaviour.

As we will see in Chapter 2, the behaviourist revolution not only changed the emphasis of psychology from the study of the mind to the study of behaviour; it also altered the methods regarded as suitable for psychology. The emphasis began to shift from introspection to the experimental method, in which observations of behaviour were made under carefully controlled laboratory conditions. What is more, if psychology is the science of behaviour, there is no good reason for studying only humans. It is relatively straightforward to measure the behaviour of other species under controlled conditions, and evolution means that one might expect to find some important similarities across species.

Current viewpoints

What is the contemporary view of the nature of psychology? Most textbooks still define psychology as the science of behaviour, but this doesn't mean psychologists agree with all the beliefs of behaviourists.

One of the differences is that most psychologists nowadays are willing to regard introspective reports of experience and thoughts as valid forms of behaviour, whereas the behaviourists were not. Another difference is that behaviourists tended to be interested in behaviour itself, but contemporary psychologists usually regard behaviour as of interest mainly because it sheds light on internal processes. In other words, behaviour is used to draw inferences about those internal processes.

We have seen how psychologists were initially concerned solely with the mind, and then more recently denied its existence altogether, so what is the current view of the mind's relevance to psychology? Many contemporary psychologists would subscribe to an "iceberg" theory of the mind, with the conscious mind corresponding to the visible tip of the iceberg. There is probably a natural human tendency to exaggerate the importance of the conscious mind, because we don't have direct access to the much larger non-conscious mind. However, a couple of examples will perhaps help to convince you that much human behaviour relies remarkably little on the conscious mind.

There are several different and complex skills involved in riding a bicycle, and yet most cyclists have almost no conscious awareness of any of the knowledge they possess about cycling. More strikingly, imagine running down a spiral staircase. If you started thinking about where to place each foot, you would greatly enhance the chances of ending up in a heap at the bottom of the stairs! In this case, use of the conscious mind would actually be disruptive rather than helpful.

There have clearly been substantial changes in psychologists' views of the nature of psychology over the centuries, although only some of the important ones have been mentioned. It is essential to realise that even current psychologists differ among themselves about the appropriate definition of psychology. The majority believe psychology should be based on the scientific study of behaviour, but that the conscious mind forms an important part of its subject matter. However, there are alternative contemporary views of the nature of psychology, and some of them are dealt with later in this book.

“Psychology is just common sense”

One of the peculiar features of psychology is the way everyone is to a greater or lesser extent a psychologist. We all observe the behaviour of other people and ourselves, and everyone has access to their own conscious thoughts and feelings.

This "everyman" factor is relevant to us, because one of the tasks of psychologists is to predict behaviour, and the prediction of behaviour is important in everyday life. The better we are able to anticipate how other people will react in any given situation, the more contented and rewarding our social interactions are likely to be.

But the fact that everyone is a psychologist has led many sceptics to belittle the achievements of scientific psychology. This is often accomplished by putting professional psychologists in a "catch-22" situation, which some find rather irritating. If the findings of scientific psychology are in accord with common sense, the sceptic argues they tell us nothing we didn't know already. On the other hand, if the findings do not accord with common sense, the sceptic's reaction is, "I don't believe it!".

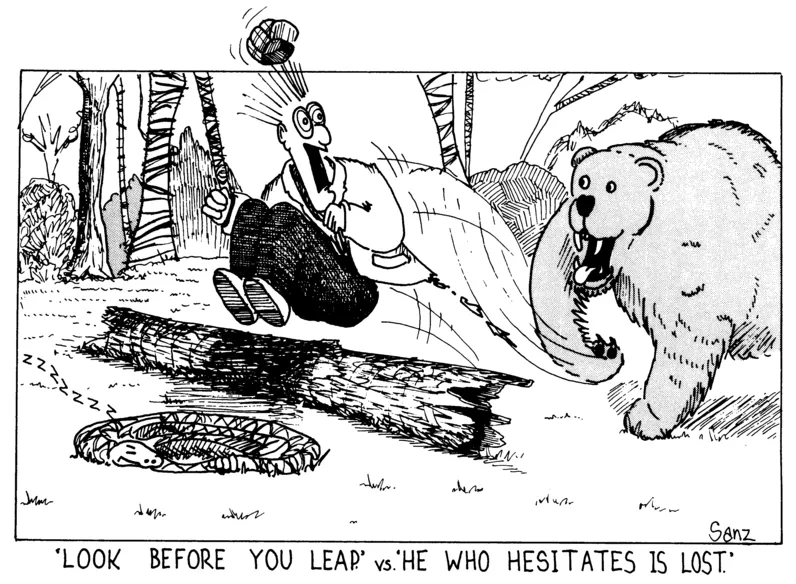

There are numerous deficiencies in the view that scientific psychology does not represent an advance on common sense, and we can look at two of the main ones. In the first place, it is misleading to assume that common sense forms a coherent set of assertions about behaviour. This can readily be seen if we regard proverbs as illustrative of commonsensical views. A girl parted from her lover may be saddened if she thinks of the proverb "Out of sight, out of mind", but she will presumably be cheered up if she tells herself that "Absence makes the heart grow fonder". There are several other pairs of proverbs which express opposite meanings—for example, "Look before you leap" can be contrasted with "He who hesitates is lost",

and "Many hands make light work" is the opposite of "Too many cooks spoil the broth". As common sense involves such inconsistent views of human behaviour, it obviously can't be used as the basis for explaining that behaviour.

The notion that psychology is just common sense can also be refuted by considering psychological experiments in which the results were very different from those most people would have anticipated.

One of the most famous examples is the work of Stanley Milgram (1974). An experimenter divided his subjects into pairs to play the roles of teacher and pupil in a simple learning test. The teacher was asked to administer electric shocks to the pupil every time the wrong answer was given, and to increase the shock intensity each time. At 180 volts, the learner yelled "I can't stand the pain", and by 270 volts the response had become an agonised scream. If the "teacher" showed a reluctance to administer the shocks, the experimenter (a professor of psychology) urged him or her to continue.

Do you think you would be willing to administer the maximum (and potentially lethal) 450-volt shock in this experiment? What percentage of other people do you think would be prepared to do it? Milgram discovered that everyone denied that they personally would do any such thing; and psychiatrists at a leading medical school predicted only one person in a thousand would go on to the 450-volt stage. In fact, approximately 50% of Milgram's subjects gave the maximum shock—which is 500 times as many people as the expert psychiatrists had predicted! In other words, people are more conformist and obedient to authority than they realise. More specifically, there is a strong tendency to go along with the decisions of someone (such as a professor of psychology) who is apparently a competent authority figure. (In case you are wondering about the fate of the unfortunate "learner" in this experimental situation, it should be pointed out that he was a "stooge" and didn't actually receive any shocks at all.)

In sum, we can see common sense isn't much use in understanding and predicting human behaviour. According to most psychologists, the best way of achieving these goals is to investigate behaviour under controlled conditions, by means of the experimental and other methods available to the psychological researcher. These methods are discussed in detail in Chapter 5.

The beginnings of psychology

The history of psychology spans a period of over 2000 years, from the ancient Greeks through to the present day. Most of the advances in psychology have happened over the past 150 years or so, but it is well worth having a brief look at some of the earlier theoretical contributions of the great philosophers and thinkers. Their views are of interest in themselves, and also provide a context within which later theory and research can be understood more readily.

Ancient Greeks

Intellectual activity flourished astonishingly in ancient Greece in the fifth and fourth centuries BC. Before that time, nearly all thinking had been either severely practical or devoted to the world of the imagination; but Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, and others introduced an abstract, critical way of thinking about people and the world. This new thinking was known as philosophy—seeking after wisdom or knowledge. The key characteristics of their approach involved a sceptical questioning of conventional beliefs.

Socrates, who lived between 470 and 399 BC, was an influential philosopher whose ideas have come down to us largely through the writings of his pupil Plato (427-347 BC). In turn, Aristotle (384-322 BC) became the pupil of Plato, and for a while was also the tutor of Alexander the Great. Although Socrates influenced Plato, and Plato influenced Aristotle, there were nevertheless major intellectual differences among them, especially between Plato and Aristotle.

Plato argued for a sharp distinction between the body and the soul. According to him, science was nothing but "a game and a recreation"; it was a "presumptious prying of man into the divine order of nature". The evidence of one's senses provided unreliable information; true knowledge could be attained only through thought.

In spite of Plato's scepticism about the value of science, he nevertheless had much to say that is relevant to psychology. For example, he made it clear in his writings that he believed in the importance of individual differences, and that such differences could have their basis in what was inherited. He compared memory with fixing impressions in wax, and suggested that individuals differ in the receptivity of "the wax in their souls". In his political writings, he compared different groups in society with different metals, with one group being likened to gold, another to silver, and a third to iron and copper. The metal of which they were formed determined their standing in society. Plato also played a major role in developing the notion of "mental health", and believed the body and the mind were both important factors. The body needed gymnastic training, whereas the mind needed a training of the emotions through the arts, and of the intellect through mathematics, Dhilosoohv. and science.

It is well known that Plato distinguished between the soul and the body, but less so that he developed a reasonably complex hierarchical theory of the soul. In essence, he argued that the soul is simply the principle of life at its lowest level, whereas the emotions are at the intermediate or desiring level. Finally, at the top level, there is the rational and intelligent part of the mind, which has the least connection with the body. There are tantalising similarities between this theory of the soul and Freud's division of the mind into the id (seat of motivational instincts), ego (rational mind), and superego (conscience).

In contrast to Plato, Aristotle argued that there was a close relationship between the body and the soul. The soul, or "psyche", was defined simply as the functioning of the active processes of the body: "It is better not to speak of the soul as feeling pity or as learning or thinking, but rather the man as doing this through the soul". The logic of Aristotle's position is that psychology should be regarded as an extension of biology—a view that is still perfectly reasonable today.

Aristotle thought scientific research was of great value in understanding human behaviour. Indeed, there are grounds for claiming that he was the first systematic scientific researcher. He believed science should proceed by making observations to establish the facts, and should then attempt to provide an explanation of those facts. Aristotle's views on the proper relationship between theory and observation have a very modern ring about them. Consider, for example, this quotation from his discussion of animal movement: "And we must grasp this not only generally in theory, but also by reference to individuals in the world of sense, for with these in view we seek general theories, and with these we believe that general theories ought to harmonise"

The popular view of Aristotle is primarily of a philosopher and a logician. However, we've already seen that he was also interested in science, and he did in fact make numerous significant contributions in this field. For example, he studied the development of the embryos in hens' eggs, which were opened at various points during incubation, and his observations made him the founder of embryology. It is particularly relevant to note his strong claims as the first psychologist, in the sense of someone committed to using theory and research to understand human behaviour. Whether or not these claims are accepted, it is indisputable that Aristotle devoted much of his attention to psychological issues.

One of the problems with evaluating Aristotle's views on psychology is that, for the most part, we have a large collection of lecture notes rather than his own written works. Nevertheless, we do know he believed that some important differences between individuals are produced by heredity, whereas others stem from habitual patterns of responding which are established early in life. This acknowledgement of the combined influences of heredity and environment on individual differences in behaviour is very much in line with contemporary thinking (see Chapter 3).

Aristotle's views on emotion also have a contemporary feel. He proposed that emotions have three essential components: the first is associated with the body; the second is the experience of ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Current approaches and historical roots

- 3. Major issues in psychology

- 4. Motivation and emotion

- 5. Research methods

- 6. The conduct of research

- References

- Glossary

- Author Index

- Subject Index