Our concern in the present chapter is the arrangement and interpretation of balance-of-payments information for purposes of economic analysis and policy assessment. Balance-of-payments accounting is illustrated briefly in the appendix to this chapter. Those interested in greater detail, especially on matters related to accounting, are advised to consult specialized sources.1

Balance-of-Payments Concepts

It is appropriate to begin by a definition : the balance ofpayments is a summary statement of all economic transactions between the residents of one country and the rest of the world, covering some given period of time.

Like many definitions, this one requires clarification, especially with respect to the coverage and valuation of economic transactions and the criteria for determining residency. The coverage of economic transactions refers to both commercial trade dealings and noncommercial transfers, which may or may not be effected through the foreign exchange markets and which may not be satisfactorily recorded because of inadequacies in the system of data collection. Particularly difficult questions of valuation are posed by noncommercial transactions and by transactions that take place between domestic and foreign-based units of individual corporations. The determination of residency should ordinarily not be difficult, but even here questions may arise concerning the treatment of overseas military forces and embassies, corporate subsidiaries, and international organizations.2

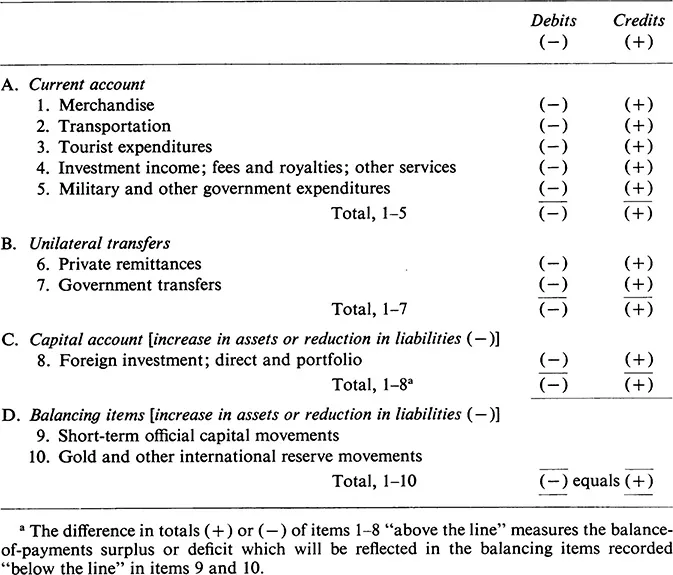

Transactions are recorded in principle on a double-entry bookkeeping basis. Each transaction entered in the accounts as a credit must have a corresponding debit and vice versa. The distributions commonly made in classifying the various accounts can be seen from the schematic balance of payments represented in Table 1.1 and from the illustrative transactions recorded in the appendix to this chapter. There are many possible interrelationships among the various items shown in Table 1.1 that arise from the complexities of the market and nonmarket transactions typically recorded for an individual nation. Thus, the receipts and payments arising from merchandise and service exports and imports shown in the current account may have their counterpart debits or credits recorded in one or more of the remaining accounts.3 The balance of payments must accordingly be looked at as a whole rather than in terms of its individual parts.

It follows from double-entry bookkeeping that the balance of payments must always balance : total debits equal total credits. When we speak therefore of a positive or negative balance or a surplus or deficit, we evidently have in mind some particular group or classification of accounts. For example, a positive balance of trade refers to an excess of merchandise exports over merchandise imports (item 1) and vice versa for a negative balance of trade. Similarly, a current-account surplus or deficit refers to the difference between receipts and payments coming from exports and imports of merchandise and services (items 1-5). As such, it represents the net contribution of foreign trade to national income and expenditure. The balances on current account and on unilateral transfers are frequently added together.4 This balance of items 1-7 constitutes a measure of net foreign investment.5

The nation’s long-term foreign investments, which are assumed to have a maturity in excess of one year, are recorded in item 8. These consist generally of direct investment in tangible physical assets of business firms and of portfolio investment in securities of various kinds. Item 8 may also include private short-term capital movements with maturity of less than one year, which represents changes in foreign- or domestic-currency working balances intended to facilitate the financing of regular commercial transactions or to take advantage of international differences in interest rates. There is some controversy, however, as to whether private short-term capital movements should be recorded in whole or in part in item 9 rather than in item 8. The argument for recording these movements in item 9 is that they may in large part be transitory in nature, and further, that they cannot be distinguished readily from official short-term capital transactions. We shall discuss these matters more fully later in this chapter. Assume for now that all the private short-term capital transactions are recorded in item 8.

This means that items 9 and 10 in Table 1.1 represent the “balancing” or “settlement” items in the balance of payments. These items are applicable in a system in which exchange rates are fixed by virtue of the nation’s monetary authority standing ready to buy and sell foreign exchange in order to keep the exchange rate at some given level or within a specified range. These official transactions may take the form of increases or decreases in short-term capital assets or liabilities or an inflow or outflow of gold or other international monetary reserves. The size of the balancing items can be interpreted consequently as a measure of the foreign exchange authority’s transactions undertaken to maintain exchange-rate stability. This suggests that if we wish in this context to speak of the balance of payments being in “equilibrium,” the sum of the balancing items should be equal to zero. There should, in other words, be no net movement of official short-term capital and of gold and other international reserves. This will be the case when the total debits and credits in items 1-8, commonly referred to as the items “above the line,” are equal. If the total debits and credits above the line are not equal, we can then speak of a positive or negative balance, or more commonly of a balance-of-payments surplus or deficit. This surplus or deficit will be reflected “below the line” with opposite sign in the balancing items 9 and 10.6 Since the sum of these balancing items follows directly from the difference in totals of items 1-8, it should be clear that the cause of a surplus or deficit cannot be inferred directly from particular items above the line.

The transactions recorded in Table 1.1 are sometimes interpreted according to whether they are “autonomous” or “accommodating” in character. Transactions are considered autonomous insofar as they may be assumed to have been undertaken in response to commercial incentives or political considerations that are given independently of the state of the overall balance of payments or of particular accounts. Thus, items 1-8 in Table 1.1 might be treated as autonomous. Accommodating transactions arise accordingly out of the need to fill the gap between total autonomous debits and credits. The filling of the gap by a nation’s foreign exchange authority, as recorded in items 9 and 10, can therefore be considered as accommodating in nature.

Table 1.1 Schematic Balance of Payments

Our discussion of the balance of payments has focused on the transactions recorded for some given period in the past and the resultant deficit or surplus. We have thus been considering an ex post conception of what has been called the “actual” balance-of-payments deficit or surplus.7 It is also possible to conceive of the balance of payments in an ex ante sense of transactions that would be carried out in given market conditions. The criterion of balance-of-payments “equilibrium” in this ex ante sense is again no net movement of short-term capital and of gold and other international reserves, but the qualification must be added that this equilibrium be sustainable for the given market period. This corresponds to what Machlup (1950) has called the “market” balance of payments.8

It is instructive to compare Machlup’s market balance with another ex ante concept, the “true” or “potential” balance, which is identified with Nurkse (1945) and Meade (1951). Both Nurkse and Meade posited that equilibrium should be defined subject to two conditions: (1) given some reference point in the past, the authorities have not imposed additional trade or payments restrictions in order to reach equilibrium; and (2) equilibrium is not attained unless there is a simultaneous attainment of full employment without price inflation. What is noteworthy about these conditions, as Johnson (1951) and Machlup (1950) have emphasized, is that they result in a definition of equilibrium that depends on political value judgments concerning the use of restrictions and the desirable level of employment. Prohibiting the use of restrictions overlooks their possible welfare benefits under certain circumstances and creates a perhaps unwarranted bias in favor of general price adjustments as a means of restoring equilibrium. This latter “ideological” point applies also to the full-employment condition, which as Machlup (1950; 1964, p. 124) has noted, amounts to “infusing a political philosophy or programme into the concept of equilibrium.”

This is not to say that value judgments have no place in economic analysis. The point is that these judgments should not be used in defining analytical concepts, but rather should furnish criteria in evaluating the workings of particular measures of economic policy. The Nurkse-Meade equilibrium concept might thus be more properly labelled as the “full-employment balance.”9 This would then make it a variant of what Machlup (1950; 1964, p. 78) has called the “programme balance,” which reflects the desires of the authorities to achieve certain specified national goals such as full employment or some particular rate of economic growth.

The question of specifying balance-of-payments equilibrium subject to the aforementioned conditions is not merely terminological in nature. For once it is granted that the authorities will carry our various policies to achieve certain national goals,10 it may no longer be possible to retain the aforementioned distinction between autonomous and accommodating transactions and therefore to talk unambiguously about a certain sized surplus or deficit in the balance of payments. There is a continuous interaction between transactions and changes in policies. Transactions may be undertaken as a consequence of particular changes in policy at home and abroad. And by the same token, changes in policy may be introduced in order to offset the effects of particular transactions that may contribute to balance-of-payments disequilibrium. There is, in other words, a shifting of cause and effect that makes it difficult to distinguish autonomous from accommodating transactions, and vice versa. The consequence is that full-employment balance-of-payments equilibrium cannot be determined precisely in an ex ante sense.

There is no unambiguous way in an actual, ex post statement of the balance of payments for any given time period to separate the autonomous from the accommodating items. It is possible, of course, to arrange the balance-of-payments accounts in a variety of manners for purposes of analysis. But it should remain clear that insofar as any arrangement hinges on imputing specific motivations of an autonomous or accommodating nature to particular classes of transactions, it is bound to involve some degree of arbitrariness.

In most countries great importance has not been attached to different possible arrangements of the balance of payments. In the United States, however, and to a lesser extent in the United Kingdom, these matters have provoked extended discussion and controversy. This has been the case especially in view of the change in the U.S. balance-of-payments position after 1958 and the special role that the dollar plays in financing world trade and in serving as a reserve currency. We turn next, therefore, to the major issues involved in the various alternative measurements of the U.S. balance of payments.

Alternative Measurements of the U.S. Balance of Payments

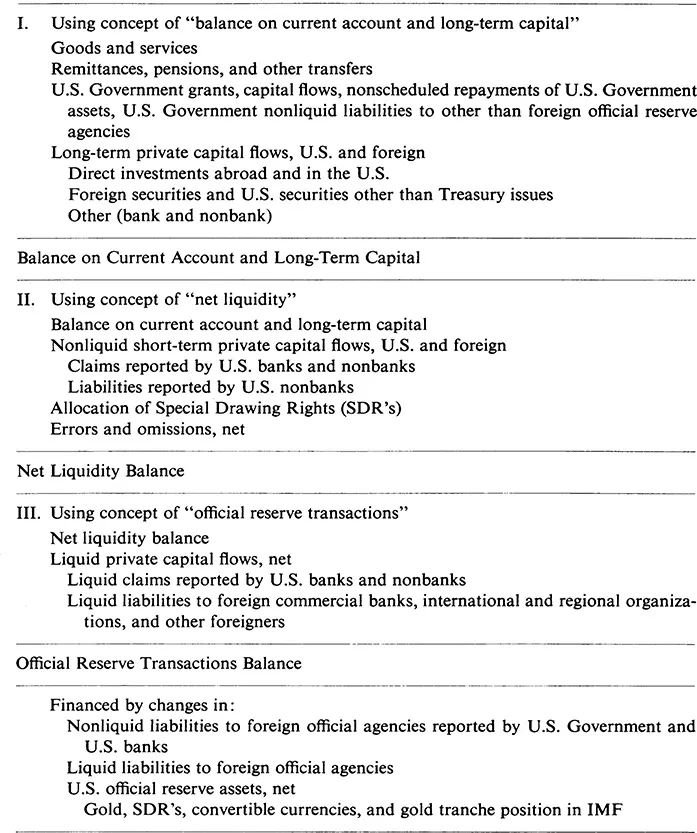

The schematic balance of payments in Table 1.1 was intentionally oversimplified in order to focus attention on the differences in various concepts. It would thus be expected that the actual balance of payments for a given country would normally contain a greater amount of detail particularly in the capital account and in the balancing items. Some flavor of such detail can be had from Table 1.2, which indicates the three main groupings of accounts that are presently (1971) in use by the U.S.,11 and from the illustrative transactions recorded and summarized in the appendix to this chapter. The actual balances corresponding to Table 1.2 are shown with minor modification for 1968-71 in Table 1.3. It is evident in reading down these tables that the two balances differ according to whether particular accounts are placed below or above the line.

The balance on goods and services indicated in Table 1.3 is equal to net exports in the U.S. national income and product accounts. It corresponds to items 1-5 in Table 1.1. The balance on current account in Table 1.3 is equal to net foreign investment in the U.S. national income and product accounts. It corresponds to items 1-7 in Table 1.1.

Table 1.2 Three Kinds of Summary Groupings of U.S. International Transactions

SOURCE: Adapted from U.S. Department of Commerce, Office of Business Economics, Survey of Current Business, 51 (June 1971), 30.

The rationale of the “balance on current account and long-term capital” is to distinguish those items above the line that are essentially more stable over time and that evolve regularly and predictably from underlying commercial and political considerations.12 The items below the line are supposed, in contrast, to be more volatile and transitory. Separation of these latter items has been further justified by Lary (1963, pp. 142-54), for example, on ...