eBook - ePub

Transforming Townscapes

From Burh to Borough: the Archaeology of Wallingford, AD 800-1400

- 507 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Transforming Townscapes

From Burh to Borough: the Archaeology of Wallingford, AD 800-1400

About this book

"This monograph details the results of a major archaeological project based on and around the historic town of Wallingford in south Oxfordshire. Founded in the late Saxon period as a key defensive and administrative focus next to the Thames, the settlement also contained a substantial royal castle established shortly after the Norman Conquest. The volume traces the pre-town archaeology of Wallingford and then analyses the town's physical and social evolution, assessing defences, churches, housing, markets, material culture, coinage, communications and hinterland. Core questions running through the volume relate to the roles of the River Thames and of royal power in shaping Wallingford's fortunes and identity and in explaining the town's severe and early decline."

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Transforming Townscapes by Neil Christie,Oliver Creighton,Matt Edgeworth,Helena Hamerow in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Wallingford in Focus

1.1 Introducing the Wallingford Burh to Borough Research Project

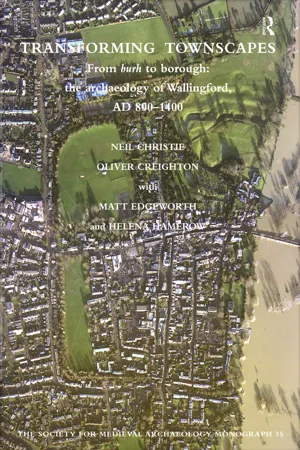

The modestly sized market town of Wallingford, now lying within south Oxfordshire but formerly part of historic Berkshire (until county redefinitions in 1974), can be rightly regarded one of British medieval archaeology’s ‘classic’ sites. The place is best known as a supposedly textbook example of an early medieval burh, or fortified centre, although it was mistakenly identified for many centuries as a former Roman town. Now widely recognised as a de novo fortification of the late 9th century AD established on the north-eastern borders of the Kingdom of Wessex, Wallingford is cited innumerable times in scholarly and popular accounts of the Anglo-Saxon period. Wallingford’s origins are usually understood within the context of the coordinated scheme of defending Wessex that left no settlement east of the Tamar further than 20 miles (30 km) from a fortress, as famously detailed in the Burghal Hidage (Hill and Rumble 1996). Within this pattern, Wallingford was part of a string of burhs spaced along the Thames, with others at Cricklade, Oxford and Sashes (near Cookham, Berkshire). Wallingford marks a signifi-cant royal foundation, part of a planned drive to defend and re-urbanise the kingdom. Aerial views of the town are frequently used to illustrate this key formative period in English urban history (see, for example, Beresford and St Joseph 1979, 195–197); they show the unmistakable rectangular plan of a ditched and embanked defensive burh circuit set against the River Thames and enclosing remnants of a tell-tale gridded street pattern (Figure 1.1).

Wallingford slots apparently neatly into several familiar narratives as an illustrative exemplar of different phases of England’s urban story: its foundation is part and parcel of King Alfred’s defence of Wessex against the Vikings through burh-building; its heyday saw a key role in William the Conqueror’s whirlwind campaigns of 1066 and witnessed the imposition of a characteristically dominant royal castle; and its decline is representative of the widespread waning of urban vitality that afflicted many towns in the later Middle Ages, as evidenced in a supposedly ‘decayed’ town plan punched full of open spaces.

Yet despite Wallingford’s high profile in Anglo-Saxon and urban studies there are surprisingly few hard published archaeological data to support and sustain these well-known stories. While the town is widely known, it remains, we would argue, little understood—or at least until recently. Brief summaries of the known state of the town’s archaeology have been published at various points in time (see, for example, Airs et al 1975, 155–162; Booth et al 2007, 136–139), but an overall account of Wallingford’s growth and decline is absent, as is any appreciation of its potential to contribute to wider urban debates. The Wallingford Burh to Borough Research Project has aimed to rectify this through a concerted programme of archaeological and historical research focused on the town and its suburbs, its built heritage and its historic landscape setting. Our project, its archaeologies and methodologies, combined with the fruits of local documentary analysis, are intended to give voice to the structures and peoples of historic Wallingford. It was formulated not only to unravel the town’s development, but also to produce a case study of urban transformation over the medieval centuries that can inform our growing understanding of the dynamics of urban growth and decline, primarily in Britain but with implications further afield, particularly in north-west Europe. While the aims, work and early results of the project have been duly reported through interim publications, conferences and webpages (as detailed below in ‘Research strategy’), this volume is the project’s principal research outcome. This first chapter highlights the special potential of a case study of Wallingford to contribute to far wider debates in early medieval and medieval archaeology and urban studies, and introduces the project, its geographical and methodological scope and its academic and intellectual rationale.

1.2 Framing the Burh to Borough Research Project

It is Wallingford’s remarkable archaeological potential in several different ways that singles the town out as a site demanding a coordinated programme of fieldwork, excavation and related research. In short, the quality, integrity and preservation of the town’s above- and below-ground archaeology mean that Wallingford arguably represents one of our very best chances of understanding not only the structure and dynamics of late Saxon urbanism generally but also the transition of these early medieval centres into the Norman period and onward into the later medieval centuries. There are three principal reasons for the town’s suitability as a case study: the high quality (or potential) of archaeological survivals and the availability of tracts of undeveloped urban and suburban space; a backlog of important but largely unpublished excavations; and the existence of a vibrant and active network of local volunteers and specialists. These factors are dealt with in turn below.

FIGURE 1.1 Aerial view of Wallingford, showing the River Thames in flood in January 2003. The sub-rectangular line of the town defences can be clearly made out, with the castle earthworks in the bottom right-hand (north-east) corner, the large open space known as the Bullcroft in the north-west angle and the smaller Kinecroft to the south-west. (Image courtesy of the Environment Agency) (see PLATE 1)

Archaeological survivals and visibilities

Perhaps the core reason for the high potential of Wallingford to address and illuminate the structures and processes of medieval urbanism relates, paradoxically, to the place’s post-medieval history. Unlike its neighbouring rivals as medieval commercial centres, namely Abingdon, Oxford and Reading, Wallingford did not emerge out of the Middle Ages as a thriving town. On the national stage also, the town’s fall from grace was dramatic: while in the late 11th century it was one of England’s top twenty towns in terms of population size, by the early 16th century it lay outside the top 300 (see Section 8.2). Intensive industrialisation and 20th-century urban development to a large extent bypassed the town, preserving an authentic historic core with a large market place at its heart. Today, sizeable sectors of the town do not have a recognisably ‘urban’ character at all: indeed, large parts of Wallingford’s modern town plan are punctuated by substantial green open spaces that existed in this form at least as far back as the later Middle Ages and quite probably earlier. Substantial swathes of space within the line of the former town defences are open land—gardens (both public and private), parks, sports fields and rough grazing—meaning that a notable proportion of the medieval urban zone is amenable to archaeological scrutiny. Three open areas in particular are relevant here (Figure 1.2): the Bullcroft, taking up the entire north-west quarter; the Kinecroft, occupying a long thin rectangular space in the south-west of the town; and the Castle Meadows and Castle Gardens, in the north-east. Of the total area enclosed by Wallingford’s ramparts, comprising 430,000 square metres or 43 hectares, a little over 32% is taken up by these three open areas (the Bullcroft comprising 5.4 hectares or 12.5%, the Kinecroft 2.1 hectares or 5%, and the Castle Meadows 6.4 hectares or 15%).

FIGURE 1.2 Wallingford: location map (above) and plan of the historic centre (below), showing principal earthworks, street names, locations of extant and lost medieval churches, and Scheduled Ancient Monuments

Further large open spaces survive along the east and west banks of the Thames, including (on the west, town, side) the Queen’s Arbour and King’s Meadow, and (on the east side) the Riverside Meadows. The only modern suburb of any scale is west of the former burghal defences; that to the south is modest and probably extends little further than it did at the town’s medieval peak, while the settlement of Crowmarsh, on the opposite (east) bank of the Thames, retains the character and scale of a village. To the north of town, the area known as Clapcot is also relatively free of development, with agricultural fields running up to the castle earthworks and Wallingford School Playing Fields taking up other areas of extramural space.

Open zones within the town plan constitute the most important reservoirs of Wallingford’s archaeology. In all of these, earthwork survey combined especially with sub-surface investigation through geophysical prospection and excavation hold considerable potential to reveal ‘lost’ features such as buildings, roads, property boundaries and other elements of pre-modern urban topography. It is a welcome coincidence that most of these open areas are owned or managed by parties with a direct interest in promoting engagement with Wallingford’s past, namely Wallingford Town Council, South Oxfordshire District Council and EarthTrust (formerly The Northmoor Trust, an Oxfordshire-based trust dedicated to landscape heritage), meaning that access to these zones for the purposes of fieldwork is relatively unproblematic. Further, somewhere between a third and a half of the historic core of the town is legally protected by designation of various component parts as Scheduled Ancient Monuments (principally the castle, bridge, ramparts, and the Bullcroft and Kinecroft), protected by the State, meaning that close liaison with English Heritage has been crucial for archaeological investigation of these zones.

Conditions of earthwork survival within these and other areas are excellent, presenting high potential to recover other elements of Wallingford’s medieval townscape through detailed analytical survey. This is particularly true in the case of the town bank and ditch (Figure 1.3). Still girding most of the historic town plan on three sides, this monument has a strong claim to represent the most important extant Anglo-Saxon town defences in England (Creighton and Higham 2005, 223), these elsewhere otherwise either surviving in vestigial form or rebuilt — the enormous banks of Wareham (Dorset), for example, were adapted as Second World War anti-tank defences. Nonetheless, it is a mistake to see Wallingford’s defences as pristine survivals of an early period of the town’s history. We should also recognise that the town defences have survived because they have been kept relatively free of development and have probably been maintained with lots of investment of labour throughout the Middle Ages and probably the earlier post-medieval period too. In this sense the town defences are as much a medieval and post-medieval monument as they are an Anglo-Saxon earthwork.

FIGURE 1.3 Wallingford’s town bank and ditch on the north side of the Kinecroft. (Photograph by Oliver Creighton)

The plan of the Norman and later castle is also intelligible and amenable to archaeological investigation, despite the paucity of upstanding masonry, as a complex and extensive suite of impressive banks and ditches and other earthwork features (Figure 1.4). This is another unusual survival, as the sites of urban castles are invariably far more disturbed, disrupted and developed. Again, however, it would be wrong to portray the castle’s complex earthworks as immaculate medieval survivals, as this zone has seen important later transformations, in particular through its adaptation as a post-medieval designed landscape of gardens, parkland and water features that may have drawn consciously on the imagery of the area’s medieval past. Whether this represented a re-casting of a medieval setting which could itself be characterised as a designed landscape is an important consideration discussed in detail elsewhere (Section 5.3). In terms of built heritage, the survival of a good stock of medieval church buildings (the town had eleven parish churches at its peak) and vernacular townhouses is a further reason why Wallingford represents such a superb testing ground for wider debates on urbanism, while the town also boasts an excellent array of medieval and later documents whose analysis is crucial to unravelling the place’s evolution. Foremost among these are the surviving rolls of the borough court, a remarkable and detailed survival that the Burh to Borough Research Project and local historians have been able to explore, building on important earlier work by Herbert (1969; 1971). Held in the Berkshire Record Office, the rolls document the activities of the medieval borough court which met on Thursdays, usually every week, had jurisdiction over a wide variety of pleas, and oversaw a range of other administrative business. These documents are particularly rich for the 13th century and are an indispensible means of adding colour and life to any account of the historic town (see Section 8.2). Nonetheless, while this project has been founded on the principle that interdisciplinary study is the most profitable way of engaging with complex questions of urban evolution, it can in no way do full justice to the rich documentary history of the town in all its forms; indeed it is recognised that a separate and extended dedicated scrutiny and analysis is required to exploit fully the court rolls and other documentary materials for both castle and town. It should be emphasised that it is accordingly the potential of the full range of documentary evidence that is considered and this volume makes no attempt at its definitive publication; but our own project, we hope, will help frame any future historical assessments.

FIGURE 1.4 Wallingford castle: earthworks and a standing fragment of the curtain wall. (Photograph by Oliver Creighton) (see PLATE 2)

Past excavations in the town and suburbs

The second key reason for Wallingford’s outstanding archaeological potential relates to a series of important and large-scale, but largely unpublished, excavations within and around the town that took place chiefly in the 1960s and 70s. These interventions highlighted the likelihood of excellent stratigraphic preservation, especially for the late Anglo-Saxon and later medieval periods, at various points around the urban area. Four sets of past excavations are relevant here. Perhaps of greatest importance are the multi-season excavations conducted by Nicholas Brooks in the mid- and later 1960s on the area around Wallingford’s former North Gate (Brooks 1965a; 1965b; 1966; 1968) (see Sections 4.3 and 4.4). These not only confirmed beyond reasonable doubt an early medieval date for the town’s earthen defences, but also revealed part of the original main road into the burh, together with related buildings and industrial activity on the street frontage, demonstrating a transforming townscape from late Saxon through to medieval times. The remarkable discovery and excavation by Robert Carr of a cob-built structure within the middle bailey of the castle in the 1970s identified the survival of part of the castle complex that was completely unknown, and recovered a sizeable animal bone assemblage (Carr 1973a; 1973b) (Section 5.5). Third, the investigation of an early Anglo-Saxon cemetery just outside the ramparts on the south-west side of Wallingford took place in the more distant past, being first discovered in the late 19th century and then being excavated by the well-known Anglo-Saxon scholar E T Leeds and others in the 1930s (Leeds 1938; see also Hamerow and Westlake 2009) (see Section 3.4). Fourth, a late Saxon half-cellared building was excavated on the Regal Cinema site in the town’s centre in 1979–80, giving us our clearest glimpse of housing and industry in this critical period of Wallingford’s urban formation (see Section 4.4). While aspects of the findings of all these excavations are known through summary publications, newspaper reports, oral accounts and archives deposited in museums and record offices, none has been fully published. Crucially, therefore, the Burh to Borough Research Project and this volume bring these four excavations to publication and contextualise them with the results of our new investigations.

The picture of Wallingford’s complex past hinted at by these major set-piece excavations, which were all to greater or lesser extents research-driven, is augmented by a proliferation of smaller-scale archaeological interventions within and around the town. These have taken place at different times, but in particular since 1990, which effectively saw the advent of ‘developer-funded’ archaeology in British towns. Within the historic core of Wallingford, evaluations, watching-briefs and trial trenches at various locations have shown stratigraphy often to be relatively undamaged by later intrusions, at least in places, meaning that analysis of even small-scale excavations can be extremely informative (see Preston 2012 for a recent compilation of such work by one archaeological unit). Furthermore, while Wallingford’...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

- List of Figures

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- Summaries

- Abbreviations

- 1 Wallingford in focus

- 2 Investigating the townscape and hinterland: methods and sources

- 3 Wallingford before the burh

- 4 The emergent burh: early medieval Wallingford

- 5 Structures of power: the castle

- 6 Approaching Wallingford castle and town

- 7 Religious landscapes: spaces, structures and status

- 8 Living, working and trading in medieval Wallingford

- 9 Provisioning burh and borough: mint, markets and landscape

- 10 Situating Wallingford

- Appendices

- Bibliography

- Index

- Plates