![]()

1 The Importance of Context in Siting Controversies: The Case of High-Level Nuclear Waste Disposal in the US

Eugene A Rosa and James F Short

INTRODUCTION

That context matters is not only one of sociology’s first principles but an enduring insight into the framing of social processes. Organizational and institutional contexts, representing cultural, economic and political interests, largely determine the course of deliberations and decision-making within which public policies are forged.

Controversies related to the siting of hazardous facilities provide many examples of this principle. Because such facilities entail serious risks, understanding the multiple contexts within which associated risks are presented to stakeholders, and the manner in which they are to be assessed and managed, is critical to successful siting projects.

Cognitive psychology has demonstrated the importance of context in framing individual perceptions and judgements under conditions of uncertainty (Kahneman et al, 1982). Less well understood, although addressed by a growing research literature, are the complex and multifaceted influences of organizational and institutional contexts that frame judgement and decisionmaking under conditions of uncertainty – that is, in short, frame the framing (see, for example, the essays in Erikson, 1994; Cohen, 2000).

Risks associated with the siting of a high-level nuclear waste (HLW) facility and their management could hardly be more complex or more daunting. This chapter examines the multiple contexts within which controversies concerning the siting of a HLW facility in the US have occurred. Our goal is to illustrate the pivotal role played by the intersecting contexts that shape the framing of issues, the definition and engagement of social and institutional actors, and the identity and actions of stakeholders.

We first review the history of US policy with regard to disposal of HLW, beginning with identification of multiple possible sites and the later decision by the US Congress to characterize a single site, located at Yucca Mountain in the state of Nevada. This legislative history is pivotal, for it led to the involvement of major institutional actors at all levels of government (federal, state and local), as well as the involvement of engineers and scientists – increasingly called the ‘fifth branch’ of government – in many disciplines, and of a variety of ‘publics’ and organizations. Social and behavioural scientists also became involved in the controversy in a variety of roles. We discuss the nature and the function of a few of these roles, and some personal experiences with them. Finally, we discuss the ‘trust conundrum’: the importance of trust relationships and involvement among those with technical expertise and the institutions and organizations with the responsibility for managing risks, and the many categories of stakeholders in the assessment and management of risks. We argue that these relationships, and these social contexts, rather than the many technical problems associated with the problem, largely explain the failure of the US to reach a working consensus regarding the disposal of HLW.

THE US CASE: WHAT WENT WRONG?

Management of HLW is one of the most challenging technological and political problems in human history. These wastes are highly lethal for at least 10,000 years, a period of time far exceeding the dynasty of any known civilization. And no nuclear nation anywhere has developed a management programme that approaches complete success.

For more than two decades the US has wrestled with the problem of HLW disposal. Yet, after the expenditure of billions of dollars and extended debate, bitter conflict continues, even though – on 9 July 2002 – Congress overrode the governor of Nevada’s veto of the repository and – on 22 July 2002 – President George W Bush signed into law the bill authorizing Yucca Mountain as the nation’s sole repository. Even in the light of these events, virtually no aspect of the debate has been settled – neither the technical nor the social acceptability of the proposed repository; and controversy is certain to continue. The state of Nevada has been preparing for both legal and technical battles of the Yucca Mountain Project (YMP) for nearly two decades and has already filed a number of lawsuits. State officials expect the nuclear industry to mount a strong lobbying/public relations campaign aimed at undermining those efforts; but they feel confident that the state’s position will be upheld (State of Nevada, 2002). Why such intransigency?

US policy and the Nevada response

The basic premise of the Nuclear Waste Policy Act of 1982 was that HLW disposal should be based on scientific validity, fairness and equity in all of its many phases. The act called for a science-based, competitive process that would assess the suitability of three sites (all in western US states) for deep geological storage of HLW in such a way as to ensure the health and safety of affected parties. In 1987, however, amendments to the act abandoned this scientifically competitive strategy and the assessment effort was directed solely to characterization of a single site located approximately 145 kilometres north of Las Vegas, Nevada, at Yucca Mountain. Responsibility for the effort was vested in the YMP. Subsequently, a large number of institutional actors (official agencies, laboratories and academies, policy-makers and university scientists) became involved in the programme. The 1987 act was pivotal, and these actors have, since that time, spent countless hours and billions of dollars engaging in lively, often contentious, debate related to implementation of the provisions of this legislation. Actors include the Department of Energy (DOE), the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission (USNRC), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the National Academy of Science (NAS) and its research arm, the National Research Council (NRC), various congressional committees and state agencies, most notably the state of Nevada and ‘affected units of local government’ (including Native American Indian tribes), as well as numerous research scholars in several disciplines. Much of this activity has been documented in official, professional and privately sponsored publications. Yucca Mountain Project expenditures, and funds spent on research related to the project, now total nearly US$7 billion. Yet the project remains controversial – scientifically, politically, ethnically and morally, and its success remains very much in question.1

Technical analyses

Perspectives of the NRC and scientists associated with universities and the national laboratory at Sandia, New Mexico, regarding the technical merits of the YMP are reviewed in the October 1999 issue of Risk Analysis, the major professional journal in the field (see Bonano and Leon, 1999; Budnitz, 1999; Eisenberg et al, 1999; Hechanova and Singh, 1999; Helton and Anderson, 1999; Helton et al, 1999; Pate-Cornell Rechard, 1999; Silva et al, 1999; Thompson, 1999).2

The authors of these articles disagree on the best procedures for conducting performance assessment (PA) of the YMP, but agree that this type of evaluation is appropriate for assessing the adequacy of the site for HLW3 and agree on geological sequestration as the appropriate means of disposal. This view is controversial and vigorously disputed by the state of Nevada, which charges that PA abandons existing standards for radiation exposure that have been set by regulatory agencies and by legislation. That is, PAs look at performance of individual components of the project, as well as total performance (TPA), rather than assessing particular risks – for example, radiation standards via air, water and seismic risks, compared to specific standards for radiation exposure and seismic vulnerability. Moreover, congressionally proposed radiation standards for the YMP are considerably lower than existing standards set or recommended by regulatory agencies and the NRC.

PA defenders are not insensitive to controversy associated with the YMP, including the need to ensure the competence and independence of site and programme evaluators, and to convince the public of safety issues and project acceptability. Staff authors of the USNRC, the key oversight body evaluating the safety of the repository, note, for example, that ‘a fundamental issue in waste system PA is the presentation of results to decision-makers and the public in a way that is understandable and allows one to discern the key elements of the analyses (ie their transparency and clarity)’ (Eisenberg et al, 1999, p873, emphasis added to original). The NRC Advisory Committee on Nuclear Waste (ACNW) ‘believes that exposure of the public to a PA process that is made more transparent could enhance public confidence in the ability of the repository to isolate waste effectively’ (Eisenberg et al, 1999, p873). Garrick and Kaplan, writing from a decision theory perspective, argue that waste disposal should be replaced by a waste management approach because it ‘leaves us in control’ (more about this later) and ‘may break the “paralysis of analysis” syndrome and allow us to move forward in a productive and relatively economical way’ (Garrick and Kaplan, 1999, p912). Precisely how this is to be accomplished is not specified; but they argue that the ‘fill-and-forget’ implication of a disposal perspective (the original rationale for a geological solution) should be abandoned for a waste management philosophy which ‘leaves us in control’, and ‘incremental confirmation and confidence-building of a permanent solution to the high-level waste problem based on science, engineering, and direct monitoring and observation’ should be permitted (Garrick and Kaplan, 1999, pp912–913).4

Nevada responds

A major source of controversy between the state of Nevada, the federal government and the scientists referenced above is precisely the increased reliance on engineered, as opposed to natural, barriers for the isolation of HLW. Engineered barriers are also a fundamental change in the approach that was specified in the 1982 and 1987 Nuclear Waste Power Acts, both of which required that safety should be ensured primarily by the natural barriers inherent in the geology of the site, with engineered barriers as back-up measures only.

The most serious technical weakness of YMP PAs, in the view of the state of Nevada, and ‘the most potentially explosive aspect of the federal programme’, is ‘the reality that tens of thousands of shipments (over 90,000 in all) of deadly spent nuclear fuel and high-level radioactive waste will travel the nations’ highways and railroads – through 43 states and thousands of communities, day after day for upwards of 40 years’ (Nevada Commission on Nuclear Projects, 2000, p4). The state charges that problems associated with the transport of waste to the Yucca Mountain site have been deliberately downplayed and that funding to investigate ‘most transportation activities has been suspended’ and ignored ‘in notices for public hearings on the draft Yucca Mountain EIS [environmental impact statement] in communities outside Nevada where such hearings were held’ (Nevada Commission on Nuclear Projects, 2000, p5).

The controversy has generated a good deal of bitterness and invective, including the charge that ‘science has given way to raw politics’ in the YMP:

What began in 1983 as a noble piece of federal legislation that sought to place science ahead of politics, and fairness, equity and openness above congressional parochialism has degenerated into a technical and ethical quagmire, where facts are routinely twisted to serve predetermined ends and where ‘might makes right’ has replaced ‘consultation, concurrence and cooperation’ as the federal mantra for the programme

(Nevada Commission on Nuclear Projects, 2000; see also, Treichel, 2000).

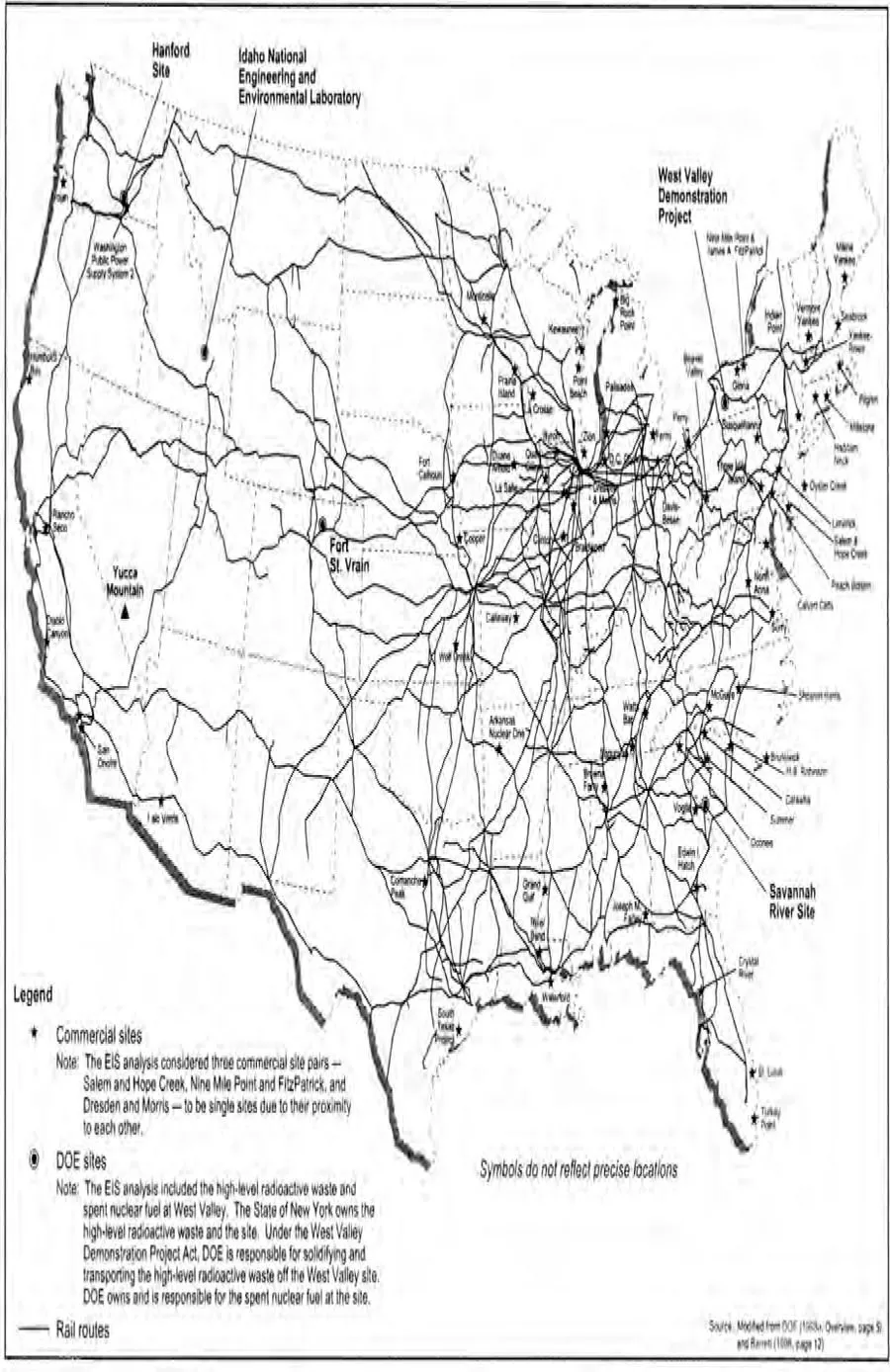

These charges reflect geographical as well as equity concerns. A key feature of the proposed repository is its location in relation to states operating nuclear power plants and its location within the state of Nevada (including its proximity to Las Vegas and to the state capital at Carson City). These features are presented in Figures 1.1 and 1.2.

Figure 1.1 Location of commercial and DOE sites and Yucca Mountain

Source: State of Nevada Office for Nuclear Projects

Figure 1.2 Yucca Mountain location

Source: State of Nevada Office for Nuclear Projects

Note that the state of Nevada has no commercial nuclear facilities. As a result, lacking the benefits of nuclear electricity but being asked to sequester nuclear waste challenged the spirit of the equity and fairness principles contained in the original act.

Another controversy, as noted above, centres on the transportation of nuclear waste from the 131 storage locations in 39 states around the country to Yucca Mountain. The transportation routes, whether by truck or rail (the only two modes of transportation anticipated), span long distances and cross numerous communities throughout the nation. Nevadans are deeply concerned about accidents in the transportation of HLW. Once transportation routes are finalized there is also the potential for the many communities along those routes to become equally concerned.

The necessary initial condition for meeting the criteria and the spirit of both the 1982 and 1987 Nuclear Waste Policy Acts was that technical and social domains of HLW disposal should be properly monitored. This required the collection and analysis of appropriate empirical data. To this end, the state of Nevada sought funds from the federal government to develop a two-pronged approach to the YMP:

1 technical monitoring of the site and the programme, including transportation; and

2 development of a comprehensive on-line data system that would serve as a baseline of the economic, demographic, social, health and cultural state of affairs in Nevada, against which to measure and project economic and social change.

When available funds proved to be inadequate for the latter purpose, the Nevada Agency for Nuclear Projects chose to focus on emergency management and transportation risks, and to devote particular attention to so-called ‘special effects’ – that is, effects on special populations (urban, rural, retirees, native tribes, local governments) and economies (property values, tourism, gaming) in Nevada due to the siting of the repository. The latter studies focused on such matters as risk perceptions and stigma attached to HLW and the YMP, and their impacts on property values, the tourist industry, state and local governmental agencies and other aspects of Nevada life, including public acceptability of a repository.

The primary strategy of the state relied on in-house funding of transportation studies and technical monitoring, while assigning the task of conducting special effects research to a ‘study team’ of outside social scientists. This strategy yielded more than 300 reports, presentations, articles, books and chapters (Flynn et al, 1995, pxi), many of them pioneering studies of risk perceptions, possible stigma effects, the role of public trust in the acceptability of the YMP, variations in and contingencies associated with public acceptance, as well as studies of transportation and economic implications of the project.

Figure 1.3 Commercial and DOE sites and Yucca Mountain in relation to the US interstate highway system

Source: State of Nevada Office for Nuclear Projects

Figure 1.4 Commercial and DOE sites and Yucca Mountain in relation to the US railroad system

Source: State of Nevada Office for Nuclear Projects

The response of Clark County

Nevada counties followed quite different strategies from the state. Clark County, where the state’s largest city and one of the most rapidly growing cities in the US (Las Vegas) is located, mounted by far the most ambitious effort.5 The Clark County Nuclear Waste Division (NWD) was established as the official agency of the county for coordinating local efforts related to the proposed repository. Initially, the division relied largely on consultants and independent research contractors to guide a programme that was focused primarily on database development and management (such as demographic and economic characteristics, and transportation and emergency response systems) and on modelling the impacts of the YMP. Studies of social impacts were added somewhat later. At first, responsibility for most of these systems and for economic modelling, database management, emergency management, technical/environmental impacts, transportation, systems development, and socio-economic and socio-cultural areas was assigned to private contractors. As time went on, however, the NWD increasingly used the US DOE pass-through funds to build inhouse staff capability in all of these functions except for the socio-economic and cultural areas – the very areas that the growing literatu...