![]()

Part One

Changing Approaches

![]()

1

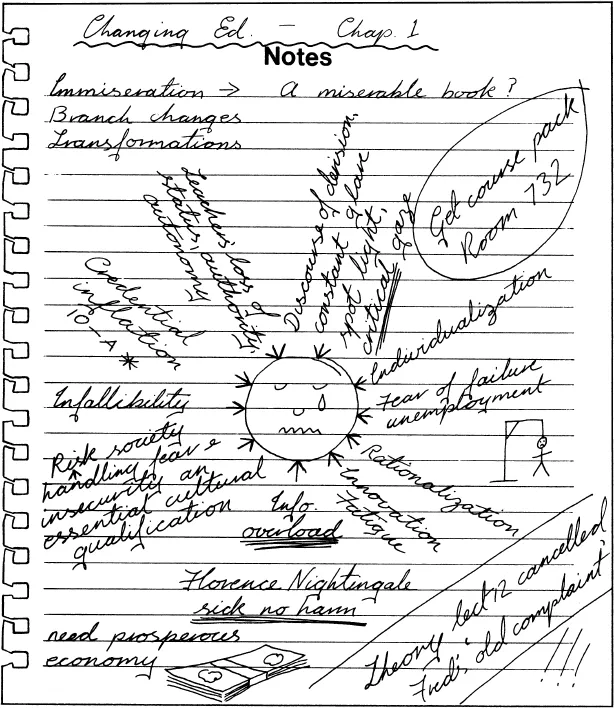

Introduction: The immiseration of education since 1944

My thesis is that in the risk society we are concerned with a type of immiseration which is comparable to that of the working masses in the nineteenth century, and yet not comparable at all.

Beck, 1992, p 51

Why has British education become so miserable? Although sociological studies of educational change involve many perspectives trying to focus on a constantly moving target, one underlying pattern seems to follow behind recent changes in education: the contemporary history of educational change has been associated with a process of gradual immiseration for many of the people concerned. True, it is always possible to cite heartening illustrations of progress and the sheer pleasure of individual educational achievements, but the one feature that stands out from a sociological study of the often confusing images of educational change is the growth of a new type of misery. This is not the misery of the downtrodden masses of the past, or of the children of the elite, who were expected to follow in their parents’ clogs or brogues. Rather it is the misery of constant endeavour to achieve an impossible ideal of perfection, in order to compete against others who are similarly pressed, and to fend off threats of exclusion in an insecure social and economic environment. It is the misery of pupils, students, teachers and workers who know that they will always be regarded as deficient in some way, always have to run in order to keep still and always be aware that unexpected changes may be imposed on them.

This long-term view of changes in education since 1944 shows that social and economic influences have led to new perceptions of what education, and a lack of education, actually signifies for the individual, and genuine fears about personal prospects for the twenty-first century. With its interest in the wider picture, sociology can study the place of education in its changing social context and appreciate how context can influence personal educational experiences. It helps us to appreciate how our personal educational histories belong to a setting in time, place and station.

Despite the many, severe and challenging faults within British education during the 1940s, the spotlight of public debate (discourse) at the time seemed to emit a relatively balmy warmth, based on plans for a new and exciting postwar future in which all children would have greater educational opportunities than ever before. Any changes were likely to be for the better. Yet, by the 1990s, education was wilting after years in the glare of the concentrated and unyielding spotlight of critical discourse, and educationalists faced prospects for the future with a sense of resignation, or even foreboding, based on innovation fatigue. What sociologists called a ‘discourse of derision’ (e.g. Ball, 1990) meant that, no matter what changes took place in education, more changes would follow, demands would never be wholly satisfied and the critical gaze would continue. Yet the role of sociology in this discourse of derision may be seen as ambiguous because, whilst criticizing the critics, sociologists are themselves critics. It is the job of sociologists to make visible problems that were previously invisible and therefore generate their own critical discourse.

Many changes are obviously essential, as progress through learning is based on a critical understanding of what is already known. Yet a basic understanding of behavioural psychology indicates that rewards, or praise, are at least as necessary as threats or criticisms (some theorists would claim even more so) in any effective training programme. In the UK such praise often seems rare and is usually directed at individual actors or schools when they are seen as outstanding within a generally derided system. The educational ‘system’ itself is badly in need of succour and sociology should be able to offer some hope as well as criticism. Because of its analysis of what is common (group behaviour, group cultures and social trends), as well as individual, a sociological approach is able to describe and explain what then becomes all too obvious; in this case that the continual reinforcement of negativity can have adverse consequences.

Surely British education must have improved since 1944! It certainly has, and the many radical improvements will be charted throughout this book. Yet, whilst many major and minor problems in education have been tackled effectively, and in some cases apparently eliminated, there was little room for self-congratulation when lingering problems immediately replaced the ones that had been tackled. If the hopes of the 1940s now seem too optimistic, the realism of more recent decades can be experienced as too depressing. In the 1940s it was widely assumed that the new education system would create opportunities for greater social mobility; the working-class child would be able to use education as a way of ‘getting on’ in life. Passing the 11+ and/or acquiring any qualifications at school-leaving age were regarded as major achievements. Yet a shortage of workers meant that even school leavers without qualifications could find jobs and sometimes choose from a variety of employment options. Despite occasional pressure from parents and teachers, young people knew that school leavers without qualifications were the norm and that they did not have to succeed in education in order to succeed in life. Once employed, promotion in ‘jobs for life’ often resulted from practical experience and longevity, rather than academic credentials. Competitiveness could be balanced by the sense of mutual dependence emerging from wartime experiences. The late 1940s was not a ‘golden age’ in which to experience education, but it was an age of relative optimism about the nature of post-war society. Just as we are currently engaged in exciting debates about the prospects for a new millennium, policy-makers and public alike were then fascinated by the prospects for life in a new society fit for heroes and built upon the experience of wartime comradeship. Public discourse about education was generally positive and optimistic and, given the scarce educational opportunities that existed before 1944, it was quite realistic to assume that anything would be an improvement.

Teachers too experienced a relatively comfortable educational environment, with high status in communities that respected them as autonomous professionals and had faith in their ability to determine the ‘secret garden’ of the curriculum. High wages, self-regulation, short hours, long holidays (when compared to the long hours and short holidays of other workers at the time) and a confident sense of authority meant that teaching came to be regarded as a relatively easy life. Although this positive image conceals a mass of educational problems, education was under a warm and pleasant spotlight, rather than the heat and glare experienced in recent years.

Many, significant, improvements have taken place during the past 60 years, but there is a sense of something not right, a feeling that British education is failing the country and that we are not developing the skills needed in order to compete with other countries in a global community. We are experiencing a never-ending search for perfection and those involved in educational institutions (as students and staff) are subject to increasing surveillance, without serious attention being paid to their emotional well-being. Along the way we may have lost an appreciation that the subjects of this critical gaze are thinking, feeling and emotional humans. Their inputs, processes and outputs are continually monitored as we would monitor those of any factory, and although some interest is shown in educational welfare (e.g. attendance, discipline and so on), happiness in the educational workplace is not a priority or a major issue for public debate.

Individualization, rationalization, mass unemployment and stiff competition for jobs have created a competitive and highly critical culture in which we are all being constantly evaluated. A competitive environment gives rise to a fear of failure, our experience of continuous criticism creates severe anxieties, and we may sense feelings of alienation from the education system itself. Moreover, whilst monetary inflation is the prime concern of most governments, the toll of credential inflation has been ignored. School leavers must now acquire as many qualifications (credentials) as possible; so much so that the highest aspirations of a child in the 1940s could be seen as failure in the child of today. A suggestion that, like monetary inflation, credential inflation could be tackled by limiting the credentials in circulation, would be met by gasps of horror for its educational barbarism. We must aim for the highest possible standards, but such standards can include unreasonable expectations of infallibility, and result in the failure of many individuals who would have been regarded as socially and economically useful citizens in the 1940s. Perceptions of success or failure change according to the criteria against which they are measured. Thus, at one extreme, the most obvious failures are leaving school with literacy and numeracy problems, no hope of a rewarding job and the prospect of social exclusion. Yet sociologists can show (see ‘Frank’s problems’ in this book) that even a lack of apparently essential skills could be balanced by other personal qualities. At the other extreme, those apparent successes who are acquiring advanced technological and other skills (of the sort that would have been regarded as science fiction in the 1940s) may not have developed the reflexive attitude needed in order to effectively utilize, evaluate and monitor that knowledge. There may be little interest in acquiring knowledge for its own sake when students work hard out of fear of the consequences of failure in an increasingly competitive and insecure society.

Teachers too are withering under the pressure to achieve perfection. Their relative reduction in wages, loss of autonomy (with the introduction of the National Curriculum, auditing, monitoring and league tables), long hours and shorter holidays (the leisure time of the past being filled by paperwork and training programmes), loss of status and authority within a changing local community, and severe discipline problems now make teaching a particularly stressful occupation (see Dunham, 1992).

By the end of the century public discourse about the behaviour of young people (e.g. drugs, alcohol, violence and various other criminal activities) was habitually critical of schools and schooling, whilst the potential for immiseration within education tended to be overlooked. Golman therefore created a best-seller (1996) when he suggested that educationalists should concern themselves just as much with emotional intelligence as with academic credentials. It was an idea many educationalists could immediately identify with. Yet the problem is not simply about how education can be used to treat or prevent existing and/or external social problems, as another, overriding problem may be about the pressure on education of social expectations. Just as Florence Nightingale observed that ‘It may seem a strange principle to enunciate as the very first requirement in a hospital that it should do the sick no harm’ (1863), it is reasonable to observe that the first requirement of an educational establishment is that it does its students no harm. Perhaps a generous spirit could add that it should also do the staff no harm, since we need to feel confident that the work they do will benefit the students.

How and when did the shift from the optimism of the 1940s to the misery of the 1990s take place? In general, although an effective education system is often seen as essential for a prosperous economy, the reverse is very rarely appreciated: a prosperous economy is essential for a thriving education system. There were certainly traces of a growing critical discourse during the 1960s but a turning point can be seen in the economic crises of the 1970s. The global oil crisis affected economies and impacted on social systems in various ways and it was difficult for the governments of Western democracies to explain to the public the apparent failure of their economic policies. It was much easier to shift the blame to education systems for not providing the necessary skilled workforce and to subsequently generate the pressure of credential inflation. Education in general, and schools in particular, could easily be treated as what A.H. Halsey et al. (1980) called ‘the wastebasket of society’ or, as Andy Hargreaves described them (1994, p 3), ‘policy receptacles into which society’s unsolved and unsolvable problems are unceremoniously deposited’. Education provided a neat and simplistic focus for otherwise disparate and complex discontents. Social trends such as mass unemployment, aging populations and changes to the traditional family meant that governments were also becoming overburdened by their responsibilities for social welfare. This provided a supportive environment for the monetarist policies of the New Right (involving cuts in educational spending) and its associated moral underclass discourse (failure in education being discussed in terms of personal inadequacies rather than unequal life chances; see Levitas, 1998). A focus on the never-ending search for better academic qualifications and infallibility in the workplace could easily ignore other, more fundamental needs.

In the risk society, therefore, handling fear and insecurity becomes an essential cultural qualification, and the cultivation of the abilities demanded for it becomes an essential mission of pedagogical institutions.

Beck, 1992, p 76

At the start of the twenty-first century the problems associated with credential inflation, information overload and infallibility are still largely unacknowledged and education is still immiserated by what has become an ingrained critical discourse. Indeed, in many ways it seems that claims that there has been a shift from old- to new-style politics (involving a shift from concerns about emancipation from oppression to concerns about reflexivity and self-actualization) do not fit comfortably with current educational discourse. The arrival of a Labour government in 1997, with its ‘Third Way’ agenda (Giddens, 1998) as an alternative to the individualist agenda of the New Right, has so far had little impact on the pressures within the education system.

This book will show that, by the 1990s, educational experiences pre-1979 had become what one informant (in the Labourville and Torytown studies) called ‘… a different culture’. In 1990 Stephen Ball described general changes in educational discourse and what he called a ‘discourse of derision’.

Some aspects of the once unproblematic consensus are now beyond the pale, and policies which might have seemed like economic barbarism twenty years ago now seem right and proper.

Ball, 1990, p 38

The focus in this book will therefore be on how such changes took place and what can be learned from them as we consider prospects for the future. We are not only looking at relatively minor branch changes (see David Hargreaves and Hopkins, 1991), associated with changes in educational practice which may be adopted, adapted or resisted, but also at more fundamental root changes (Andy Hargreaves, 1994), those deeper transformations affecting how education is socially organized and experienced; such as the increasing emphasis on market values. We are not looking...