eBook - ePub

Voices from the Forest

Integrating Indigenous Knowledge into Sustainable Upland Farming

- 826 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Voices from the Forest

Integrating Indigenous Knowledge into Sustainable Upland Farming

About this book

This handbook of locally based agricultural practices brings together the best of science and farmer experimentation, vividly illustrating the enormous diversity of shifting cultivation systems as well as the power of human ingenuity. Environmentalists have tended to disparage shifting cultivation (sometimes called 'swidden cultivation' or 'slash-and-burn agriculture') as unsustainable due to its supposed role in deforestation and land degradation. However, a growing body of evidence indicates that such indigenous practices, as they have evolved over time, can be highly adaptive to land and ecology. In contrast, 'scientific' agricultural solutions imposed from outside can be far more damaging to the environment. Moreover, these external solutions often fail to recognize the extent to which an agricultural system supports a way of life along with a society's food needs. They do not recognize the degree to which the sustainability of a culture is intimately associated with the sustainability and continuity of its agricultural system. Unprecedented in ambition and scope, Voices from the Forest focuses on successful agricultural strategies of upland farmers. More than 100 scholars from 19 countries--including agricultural economists, ecologists, and anthropologists--collaborated in the analysis of different fallow management typologies, working in conjunction with hundreds of indigenous farmers of different cultures and a broad range of climates, crops, and soil conditions. By sharing this knowledge--and combining it with new scientific and technical advances--the authors hope to make indigenous practices and experience more widely accessible and better understood, not only by researchers and development practitioners, but by other communities of farmers around the world.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Voices from the Forest by Malcolm Cairns in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Ecology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Introduction

A Matigsalug villager in Mindanao, the Philippines.

Chapter 1

Challenges for Research and Development on Improving Shifting Cultivation Systems

The many contributors to this volume seek to explore and interpret, perhaps in a more determined manner than ever before, the most successful strategies developed by farmers and communities throughout Asia and the Pacific to sustain threatened shifting cultivation systems. From that exploration, we aim to develop a set of methods to put that knowledge to work for the benefit of the many communities facing a crisis of livelihood and declining natural resource quality.

In a region of dynamic economic growth, it is inequitable that upland farming people are not benefiting adequately. Those who make their living through shifting cultivation are resourceful and hard working, and they usually husband their resources carefully. But due to circumstances beyond their control, their efforts are being rewarded with a declining resource base that traps them in poverty. In many cases, they are becoming poorer. Outsiders usually misunderstand them and their farming systems, particularly the very people in their own governments who are charged with helping them to overcome their livelihood challenges with dignity. Consequently, solutions proposed and imposed from the outside usually do not address their needs constructively, and often make matters worse.

It is time to examine the ways of the more successful upland farmers and to understand the systems they have developed to enable them to farm sustainably and intensify their fallow management systems (Sanchez 1999). Many ingenious practices exist, developed through closeness to the land and an awareness of local ecology. What if these practices, these solutions, were really understood, refined for wider dissemination, combined with new scientific knowledge and technical advances, and spread to a vastly larger population of farmers and communities? And how much good might come for the upland peoples, through this sharing of their knowledge?

This volume reviews, classifies, and characterizes outstanding solutions—developed by indigenous upland people—to the challenges of improving fallow management. Our objective must be to collaborate and maintain networks to ensure that, when all is said and done, we will see the impact of these practices upon a much broader population of farm families and communities in Asia.

My own institution, the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF), is deeply committed to this mission. Along with many countries and organizations, it is a partner in the Alternatives to Slash-and-Burn (ASB) program. We are trying to identify and highlight best bet alternative land-use systems in tropical countries around the world and to pinpoint the policies that have enabled them to flourish (Buresh and Cooper 1999). We are part of a concerted scientific effort to develop more sustainable and intensive systems of fallow rotation, or shifting cultivation.

Researching and Developing Indigenous Fallow Systems

My concern for volumes like this is that a hundred points of light will shine, but, in the end, they will have no focus. I fear that we could conclude with an outstanding collection of studies that are merely anthropological curiosities. You will note, however, that the vast majority of the exemplary systems documented herein are practiced only on a very limited area. This could mean that they have no extrapolation potential—that there are constraints to their spread that may be subtle and unrecognized. But it could also mean that modest efforts to extend these techniques to wider areas might have great impact. We must not be satisfied to simply report on them and leave them as curiosities. We must ensure that knowledge of the really useful practices is shared widely.

There are many aspects to consider when conducting research on indigenous fallow innovations with the aim of benefiting a wider population of upland people. Special care must be taken to develop research methods specifically for the unique conditions of shifting cultivation. Let me outline some of these issues, with special attention to some of the pitfalls into which we may fall.

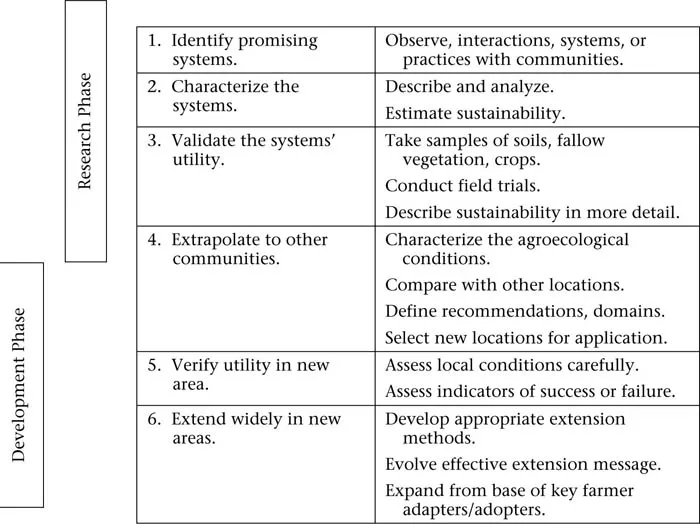

The research and development process for improved fallow management systems is a continuum of tasks. These stages are illustrated in Figure 1-1. The process begins with the identification of a promising system or practice. Limited observation indicates that the system has elements that may be of real value elsewhere and the returns to investment in research look positive. This should lead to a characterization of the system and a more thorough description and analysis based on rapid or participatory appraisal methods, perhaps complemented by more in-depth surveys. An indicative analysis of the pros and cons of the system and the nature of its contribution to sustainability should follow.

Figure 1-1. The Process of Research and Development of Indigenous Fallow Management Systems

Source: Cairns and Garrity 1999.

If, at this point, the system still appears to have development and extrapolation potential, it is time to validate this assumption by sampling soils and fallow vegetation more thoroughly and studying crop performance. This might be done by comparing fields in which the practice is employed with fields in which it is not. However, it may be difficult to achieve valid comparisons using this approach because of site factors that may confound the interpretation. It will often be necessary to conduct new field trials, particularly to test additional management variations. If the innovation still shows promise of wider application, then a dissemination process is next.

To extrapolate the innovation to other communities, one must select new locations where the agroecological and social factors are not too dissimilar. The degree to which the innovation’s success may be affected by specific biophysical conditions such as soils, rainfall, and elevation, as well as culture and land tenure, must be kept in mind. When new locations are selected, it is tempting to barge ahead with an extension program in the hope of seeing rapid impact. But it is best to verify the practice with a few key farmers before embarking on wholesale dissemination. This provides the chance to adapt the innovation to the realities of its new environment and possibly avoid a serious failure. As the success of the key farmers becomes evident, it is time to develop an effective extension program that expands adoption widely. The key farmers become the foundation for the diffusion process. Let us now examine some of these issues in more depth.

The Critical Assessment

Assessing the utility of an improved fallow innovation is a complex business. There are many snags that researchers and extension workers may find along the way:

• Analyses may show that the innovation has better returns per hectare but ignore the labor requirements. Shifting cultivation is, by definition, a system where labor is a dominant constraint. Increasing the returns to labor is usually much more important than merely increasing the yield. Thus, realistically estimating labor requirements and comparing them against other options is crucial.

• There may be a failure to examine the benefits and costs over the entire fallow rotation cycle. The effects of an innovation must be considered over the whole cycle, and not just for one or two crop seasons. Actual observations should continue even in cases where the entire rotation may extend for several years or even decades. Even if the benefits and costs have to be estimated hypothetically, it is critical to consider the entire cycle.

• Invalid or inconclusive sampling of soils and crop performance can be deceptive. It is difficult to detect unambiguous improvements in soil fertility during a period of a few years’ fallow. Many soil scientists believe that conventional soil analyses are simply not precise enough or do not measure the really important parameters. Also, the results of samples analyzed in successive years may be badly confounded by variations caused by changes at the laboratory itself. This can muffle or negate the modest changes expected in the bulk soil properties. The fertility benefit of an innovation may derive from the litter, rather than from changes in the actual fertility of the soil during the fallow period. Alternatively, the nutrients accumulated in the biomass of the fallow vegetation may provide the dominant effect.

• Attempts to compare the performance of an innovation by sampling fields where it is practiced, and comparing the results with nearby fields where it is not practiced, are often fraught with problems. Soils, slopes, cropping history, and many other farm-to-farm management differences confound such comparisons and may easily overwhelm the effects of the innovation. Or they may falsely suggest that the innovation is better than it is. Comparisons based on such sampling methods must be designed very carefully. Even in the best of cases, such results are only indicative and are tricky to interpret. This is why it is often necessary to install new trials that are designed specifically to make valid comparisons. The simplest approach is to conduct paired-plot trials. These compare the innovation with the conventional fallow system side by side on either half of a field. Replication is done across a number of farms.

The above advice directs attention to the serious challenges of conducting research in indigenous innovations. Collecting valid results is the fundamental first step. Subjecting them to a critical analysis that takes into account the shifting cultivator’s decision framework is the second step. This sustainability analysis itself must be validated and enriched with local opinions.

At this point, let us assume that we have solid evidence that our innovation is widely useful and deserves to be disseminated widely.

Facing the Constraints to Extension

There are perhaps four major constraints in conducting extension among shifting communities:

• They are usually remote from roads and market infrastructure. This means that they are constrained in participating in the market economy and may be limited in their livelihood options. It also means that extension agencies have little presence in these areas.

• There may be problems with extension agency jurisdiction. Shifting cultivation communities often live on land that is classified as forest and claimed by the state. Agricultural extension agencies are often not permitted to work with farmers on state forest land. As well, these agencies are usually understaffed.

• Land tenure uncertainty plays an important role in household land-use decisions. There is often a conflict between the claims of the state and the realities of the local land tenure system. These may be exacerbated by land conflicts within the community. Adoption of fallow management innovations will be very sensitive to these realities.

• Land use in shifting cultivation communities is often transitional. Land-use intensification is an almost universal, historical process. It typically proceeds from long-cycle fallows to continuous annual farming. Any particular improved fallow management system may be relevant to a farm or community at only one time period in this evolutionary process, but not at others. Successfully introducing innovations in fallow management is, therefore, shooting at a moving target.

Conclusions

There are many unique challenges for research and development on improved shifting cultivation systems. If this volume provides a springboard for a vigorous new international initiative on indigenous strategies for their improvement, then we can take pride that this work has truly come of age and will make a real difference in the lives of upland communities.

References

Buresh, R.J., and P.J.M. Cooper. 1999. The Science and Practice of Short-Term Improved Fallows. Selected papers from an International Symposium, Li...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- PART I. Introduction

- PART II. Retention or Promotion of Volunteer Species with Economic or Ecological Value

- PART III. Shrub-based Accelerated Fallows

- PART IV. Herbaceous Legume Fallows

- PART V. Dispersed Tree-based Fallows

- PART VI. Perennial-Annual Crop Rotations

- PART VII. Agroforests

- PART VIII. Across Systems and Typologies

- PART IX. Themes: Property Rights, Markets, and Institutions

- PART X. Conclusions

- Botanical Index

- Ethnic Group Index

- Subject Index