- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Marion Milner

About this book

In this series, Emma Letley has worked with the Marion Milner estate to re-contextualisesix classic volumes by arranging for experts to provide new scholarly introductions to each book.

Thissix volume pack comprises:

- The Hands of the Living God

- On Not being Able to Paint

- Eternity's Sunrise

- A Life of One's Own

- An Experiment in Leisure.

- Bothered by Alligators

These volumes will be useful and relevant to seasoned analysts as well as those new to Milner's work, making them attractive to a whole new generation of readers from both inside and outside of the psychotherapy profession.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

I

The emergence of the free drawings

(Firing of the imagination)

1

What the eye likes

‘O, down in the meadows the other day,

A -gath ’ring flowers, both fine and gay,

A -gath ’ring flowers, both red and blue,

I little thought what love could do ‘

Folk Song

I had tried various obvious ways of learning how to paint, such as special painting lessons at school, evening classes in life drawing, sketching during holidays and visiting Art Galleries in the lunch hour and on Saturdays. But both the life drawings and the sketches were vaguely disappointing, they gave no sense of being new creations in their own right, they seemed to be only tolerably good imitations of something else; in fact, to be counterfeits.

Then I had begun to read books about the nature of the painter’s problems. All the years previously I had painted blindly and instinctively, it was only discontent with the results that was the spur to trying to discover something about the technical problems the painter was trying to solve.

At first the books on how to paint seemed likely to provide help. They talked about the need for a sense of pattern in the arrangement of lines and masses, of darks and lights, about colour contrasts and harmonies, matters I had never deliberately thought about before. But the result of trying to put this new-found knowledge into practice was that anything done according to the learnt rules still had a counterfeit quality.

One of the books, however, said that the aim of painting was that the eye should find out what it liked. This seemed a useful idea, for it coincided with something I had already discovered about living many years since; a new world had then revealed itself as the result of an attempt, by keeping a diary, to find out what had seemed most important in each day’s happenings. But as applied to drawing it was not so easy. One could see a tree that looked lovely, but in beginning to draw the sense of what the eye liked about it could disappear; indeed it often seemed not worth risking the attempt to draw, if with the first few lines the sense of the loveliness might so vanish away. But one thing was quite clear. There was no doubt that drawings which were a fairly accurate copy of an object could produce an almost despairing boredom; so I was forced to the conclusion that copies of appearances were not what my eye liked, even though what it did like was not at all clear.

In another book I read that the essential of a good drawing was that the lines should be a genuine expression of a mood. Here was no reference to the object one was drawing, so it seemed a hopeful approach, it offered a possible way of breaking through this barrier of appearances. But when it came to the point of actually expressing a mood in lines and shapes it was a different matter. For instance, the books said that upright lines expressed dignity and power, horizontal lines restfulness, an upward curve exuberance, a sharp angle quick movement, a blunt angle slow movement. However true this might be it did not seem to help the expression of my own mood, there seemed to be no connection between moods as lived and anything that appeared on paper.

It was a long time before it occurred to me that one of the difficulties here might be something to do with a very careful selection of the moods to be depicted, an attempt to find expression for quiet and ‘beautiful’ ones only. This did not become apparent until after making my first surprising discovery.

Just as having once found that writing down whatever came into one’s head, however apparently nonsensical, could reveal a meaning and pattern that one would never have guessed at, so I had now thought that drawing without any conscious intention to draw ‘something’ might also be interesting. The first attempts had not seemed to mean much and had no value as drawings. But one day, when filled with anger over a quarrel, I had turned to such free drawing in a desperate attempt to relieve the mood of furious frustration. Here is a note, made afterwards from memory, of what ideas had accompanied the actual process of drawing:

Fig. 1: ‘I’ll have a large sheet of paper this time and charcoal, yes, it makes a good thick line … now… that’s only a scribble, what’s the good of that? It looks like a snake, now it’s a serpent coiled round a tree, yes, like the serpent in the Garden of Eden, but I don’t want to draw that, oh, it’s turning into a head, goodness, what a horrid creature it is, a sort of Mrs. Punch, or the Duchess in Alice. How hateful she is with that hunched back and deformed hand and all that swank of jewelry.’

Figure 1

When the drawing was finished the original anger had all vanished. The anger had apparently gone into the drawing. So it seemed that here at least was an expression of a mood, even though it was not an original expression, but an unconscious adaptation of the Duchess in Lewis Carroll’s famous book.*

This experience provided a first hint that some of the difficulties of achieving a genuine expression of mood might be due to the kind of mood seeking expression. One day, several years later, I saw a girl in an underground train, her toes turned in and a rapt, brooding expression which at once caught my attention. In herself she showed some of that inner intensity of living that always stirred the impulse to draw and I had read somewhere that one should always try to get at least something down on paper when such feelings occurred. On reaching home I had begun a sketch in charcoal, feeling that the mood to be expressed was a real aesthetic pleasure in beauty of form, to be embodied in a serious drawing of artistic worth. Instead, Figure 2 appeared.

Figure 2

Figure 3

Thinking over all this it occurred to me that preconceived ideas about beauty in drawing might have a limiting effect on one’s freedom of expression, beauty might be like happiness, something which a too direct striving after destroys. But nearly all my drawings so far had been determined by a wish to represent beauty. I decided that the next time such a feeling occurred it would be worth trying some experiments. So, when sitting in a buttercup field one Sunday morning in June, watching the Downs emerging from the mist, I checked the impulse to make a water-colour sketch which was certain to be a failure. Instead, I concentrated on the mood of the scene, the peace and softness of the colouring, the gentle curves of the Downs, and began to scribble in charcoal, letting hand and eye do what they liked. Gradually a definite form had emerged and there, instead of the peaceful summer landscape, was a blazing heath fire, its roaring flames leaping from the earth in a funnel of fire, its black smoke blotting out the sky (Fig. 3). This was certainly surprising, in fact it was so surprising it was hard to believe that what had happened was not pure accident, perhaps due to the fact that random drawing in charcoal easily suggests smoke. But the following week-end I was again urged to draw something beautiful, when sitting under beech trees on another perfect June morning and longing to be able to represent their calm stateliness. Once again I had tried the experiment of concentrating on the mood and letting my hand draw as it liked. After absent-mindedly covering the whole page with light and dark shadings I suddenly saw what it was I had drawn (Fig. 4). Instead of the over-arching beeches spreading protecting arms in the still summer air, there were two stunted bushes on a snowy crag, blasted by a raging storm.

This, coupled with the heath fire drawing, suggested that the problem of expression of mood, so cheerfully disposed of in the instructions, was not so simple as it sounded; for it seemed very odd that thoughts of fire and tempest could be, without one’s knowing it, so close beneath the surface in what appeared to be moment of greatest peace.

Figure 4

After this I found it was often possible to make drawings by the free method, even without the stimulus of strong conscious feeling about some external object. It was enough to sit down and begin to scribble and the scribble would gradually become a drawing of something. It was usually something rather phantastic, but not always; sometimes it was a single object, sometimes a dramatic scene, sometimes a surrealist conglomeration of bits. Occasionally it would remain just a scribble.

Also, although the drawings were actually made in an absent-minded mood, as soon as one was finished there was usually a definite ‘story’ in my mind of what it was about. Most often these stories had been written down at once but even when not so noted I could remember their exact details years after, they seemed to be quite fixed and definite, having none of the elusive quality of dreams. But I could not at this stage bring myself to face the implications of the fact, though recognising it intellectually, that the heath fire and blasted beeches and girl in the train drawings all expressed the opposite of the moods and ideas intended.

Note

* Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland with John Tenniel’s illustrations had been one of the most familiar books of my childhood.

2

Being separate and being together

‘The water is wide,

I cannot get o’er,

And neither have I wings to fly.

Give me a boat that will carry two,

And both shall row, my love and I.’

Folk Song

Instead of trying to puzzle out the meaning of the free drawings I went on trying to study the painter’s task from books. Up to now I had assumed that all the painter’s practical problems to do with representing distance, solidity, the grouping of objects, differences of light and shade and so on were matters for common sense, combined with careful study. But when I tried to begin such careful study there seemed some unknown force interfering. Of course I was already familiar with the idea that one’s common sense mind is not all there is, and that when it is difficult to do something that the common sense mind says is straightforward and should be done, then one must expect the imaginative mind to have quite other views on the matter. But I had not up to now thought of applying this to painting. When I did, it was clear that the imaginative mind could have strong private views of its own on the meanings of light, distance, darkness and so on. For instance, I began to find that it had some very definite ideas of its own about the subject of perspective and that these ideas were in fact being illustrated in some of the drawings.

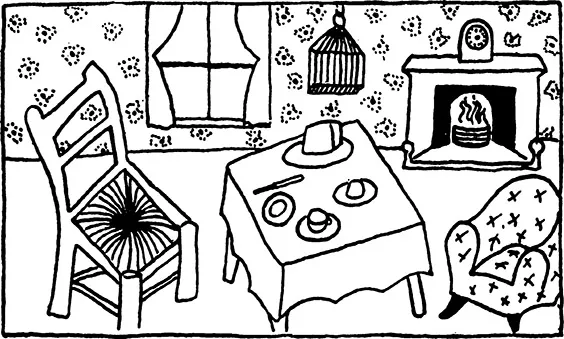

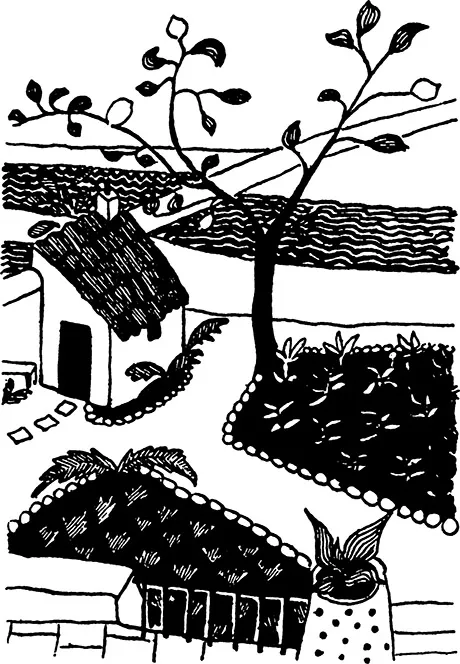

In spite of having been taught, long ago at school, the rules of perspective, I had recently found that whenever a drawing showed more or less correct perspective, as in drawing a room for instance, the result seemed not worth the effort. But one day I had tried drawing an imaginary room (Fig. 5) and after a struggle, had managed to avoid showing the furniture in correct perspective. The drawing had been more satisfying than any earlier ones, though I had no notion why. Now it occurred to me that it all depended upon what aspects of objects one was most concerned with. The top of a table, for instance, could be considered as a supporting squareness on which to lay the breakfast, not as a flattened shape with side-lines fading off to a vanishing point, as it seems to the contemplative eye when one sits down to make a sketch of it. And so with chairs, the important thing about a chair seemed to be that it is below one, ready to support one’s weight; and that was how I wanted to draw it. Gardens introduced a similar question of view-point; I found I wanted to draw a garden looking down on it from above, so that one was, as it were, more nearly inside it and surrounded by it (Fig. 6). It was as if one’s mind could want to express the feelings that come from the sense of touch and muscular movement rather than from the sense of sight.

Figure 5

In fact it was almost as if one might not want to be concerned, in drawing, with those facts of detachment and separation that are introduced when an observing eye is perched upon a sketching stool, with all the attendant facts of a single viewpoint and fixed eye-level and horizontal lines that vanish. It seemed one might want some kind of relation to objects in which one was much more mixed up with them than that.

Figure 6

At first I thought that such an unwillingness to face the visual facts of space and distance must be a cowardly attitude, a retreat from the responsibilities of being a separate person. But it did not feel entirely like a retreat, it felt more like a search, a going backwards perhaps, but a going back to look for something, something which could have real value for adult life if only it could be recovered. It almost seemed like a way of looking at the world which the current, ‘reasonable’, common sense way had perhaps repudiated, but a way which might have potentialities of its own at the appropriate time and place, a kind of uncommon sense that one needed.

Somewhere in the books it was stated that painting is concerned with the feelings conveyed by space. This was surprising at first, up to now I had taken space for granted and never reflected upon what it might mean in terms of feeling. But as soon as I did begin to think about it, it was clear that very intense feelings might be stirred. If one saw it as the primary reality to be manipulated for the satisfaction of all one’s basic needs, beginning with the babyhood problem of reaching for one’s mother’s arms, leading through all the separation from what one loves that the business of living brings, then it was not so surprising that it should be the main preoccupation of the painter. And when I began to feel about it as well as think about it then even the whole sensory foundation of the common sense world seemed to be threatened. For instance, I remembered a kind of half-waking spatial nightmare of being surrounded by an infinitude of ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Note to second edition

- New introduction

- PART I The emergence of the free drawings (Firing of the imagination)

- PART II The content of the free drawings (Crucifying the imagination)

- PART III The method of the free drawings (Incarnating the imagination)

- PART IV The use of the free drawings (The image as mediator)

- PART V The use of painting

- APPENDIX

- Bibliography to first edition

- Bibliography to second edition

- Description of original drawings

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Marion Milner by Marion Milner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Mental Health in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.