![]()

PART I

Encoding, Storage, and Retrieval in Prospective Memory

![]()

1

Prospective Memory or the Realization of Delayed Intentions: A Conceptual Framework for Research

Judi Ellis

University of Reading

As Neisser observed, ordinary language employs the word remember to reflect at least two different temporal perspectives: “remembering what we must do” or our future plans and “remembering what we have done” or events from the past (Neisser, 1982, p. 327). The former is termed prospective, and the latter, retrospective remembering, following Meacham and Leiman (1976).

The use of the term prospective remembering, or prospective memory, often carries an implicit assumption that one might be dealing with a distinct form of memory. Indeed, it is often contrasted with research on more extensively studied memory tasks described as examining retrospective memory, such as the free recall or recognition of previously learned word lists. In this chapter, however, I suggest that the term prospective memory may be a misleading or inadequate description of research on the formation, retention, and retrieval of intended actions or activities that cannot, for whatever reason, be realized at the time of initial encoding. Successful prospective remembering can be described, therefore, as processing that supports the realization of delayed intentions and their associated actions. As such, it is intimately associated with the control and coordination of future actions and activities.

The primary aim of this chapter is to develop this analysis of prospective memory tasks into a broad conceptual framework. It draws from research on a variety of cognitive processes and places prospective memory at the interface between memory, attention, and action processes. For this reason the description, realizing delayed intentions, is used here whenever it is appropriate to do so, in preference to the term, prospective memory. The final section briefly examines the implications of this framework for future research questions and methodologies.

PHASES OF A PROSPECTIVE MEMORY TASK

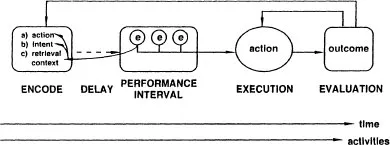

The realization of a delayed intention and its associated action is described in terms of the following general phases,1 illustrated in Fig. 1.1:

A. Formation and encoding of intention and action.

B. Retention Interval.

C. Performance Interval.

D. Initiation and Execution of Intended Action.

E. Evaluation of Outcome.

Phase A is concerned primarily with the retention of the content of a delayed intention. More precisely, it is concerned with the retention of an action (what you want to do), an intent (that you have decided to do something) and a retrieval context that describes the criteria for recall (when you should retrieve the intent and the action and initiate them). For example, the different elements of an intention to telephone a friend this afternoon may be encoded as follows: “I will” (that-element) “telephone Jane” (what-element) “this afternoon” (when-element). It is highly probable that planning and motivational operations that occur during this phase will influence the encoding and thus the eventual representation of the delayed intention.

Phase B refers to the delay between encoding and the start of a potential performance interval, whereas phase C refers to the performance interval or period when the intended action should be retrieved.2 This distinction between retention and performance intervals is illustrated by the following example. An intention to visit a friend tomorrow morning may have been encoded 2 days ago. It would have, therefore, a retention interval of approximately 2 days and a performance interval of approximately 3 hours (9:00 a.m.–12:00 p.m.). The duration of retention and performance intervals will vary considerably and a delayed intention may be remembered at any point during either of these two phases. The successful realization of an intention, however, requires that it be retrieved on at least one occasion during a performance interval and on the occurrence of the following events. First, an appropriate situation must be recognized as an occasion that is (a) a retrieval context and (b) associated with a particular intention to do something: retrieval of the when- and that-elements. Second, the action that was encoded with these elements must be retrieved—recall of the what element. Phases D and E are concerned with the initiation and execution of an intended action, and the evaluation of the resultant outcome, respectively. Moreover, some form of record of an outcome is necessary either to avoid an unnecessary repetition of a previously satisfied delayed intention or to ensure the future success of a postponed or failed delayed intention.

FIG. 1.1. Schematized view of the phases involved in the realization of a delayed intention. Note. e = event, and so forth, to signal retrieval context.

Einstein and McDaniel (1990) proposed that we can usefully discriminate between two components of a prospective memory task. The first retrospective memory component refers to the retention of the action and “target event” or retrieval context. The second prospective memory component refers to the retrieval of the action “at the appropriate time or in response to the appropriate event” (p. 725). These two components correspond broadly to operations postulated to occur during phases A and C, respectively (see Fig. 1.1). To facilitate a more comprehensive and componentially neutral analysis of the task of realizing a delayed intention, these components are referred to here as retrospective (phase A) and prospective (phases Β through to E). The exclusion of the term memory is a deliberate step designed to avoid a potential bias toward only considering “pure” memory processes.

TOWARD A CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK: COMPONENTS AND PROCESSES

The Retrospective Component

This consists of the what- (action), that- (intent), and when- (retrieval context) elements that together form the content of a delayed intention. These elements are considered briefly here and examined in more detail at a later point.

The action or what-element will vary with respect to its overall complexity and the origin of this complexity. It may describe, for example, a physical or mental activity that varies from the relatively routine or well-learned to the relatively nonroutine or novel.3 The less routine the action, or part of that action is, the more likely it becomes that planning processes, concerned with how the action is to be performed (what-realization), will be required (see also, Ellis & Shallice, 1993). The application of these planning processes is likely to result in a more detailed encoding of constituent action components for a non-routine action (see, e.g., Kolodner, 1983; Schank, 1982).

Complexity may be also derived from a requirement to either carry out several relatively independent enabling actions prior to the intended action, or execute several constituent actions in the pursuit of a particular extended activity. For example, in order to carry out an action such as photocopying a journal article, you may need to carry out enabling actions such as discovering the library that stocks that journal and/or completing an interlibrary request form. Alternatively, photocopying may describe an activity that requires the performance of more than one action, such as making more than one type of copy of the article (e.g., a double-sided version and a reduced-size copy). In general, as the number of these enabling and/or constituent actions increases, the demands of that action in terms of encoding and retention will also increase. However, these demands will be mediated by the temporal or causal connections either between constituent actions or between enabling actions and the initially intended action (see, e.g., Schank, 1982). Finally, the action may require the transmission of information. Here, as before, the number of items to be relayed or requested, the degree to which they have been learned previously, their semantic relations, and so on, will all exert an influence on encoding demands (see, e.g., Mandler, 1967; Tulving, 1962).

The intentional status of a delayed intention (or that-element) refers to a decision or readiness to act—the notion of “something to do” at a future moment (see, for further discussion, Kvavilashvili & Ellis, this volume). It incorporates motivational forces that reflect one’s degree of commitment to the realization of that intention. The intentional status of an intention may vary from a wish or want to a must, ought, or will (see, for further discussion, Kuhl, 1985). This “strength” of an intention may reflect not only its personal importance, but also the potential benefits of realizing it as well as the costs of failure. Although these three dimensions (personal importance, benefits, and consequences) are highly correlated in naturally occurring intentions (Ellis, 1988a, 1988b) there are occasions on which they appear to be in conflict. For example, a personally important intention, such as buying a new item of clothing, may confer a high degree of personal benefit but relatively low consequences if one fails to satisfy it. The strength of a delayed intention, moreover, is likely to be influenced further by (a) its origin or primary source (oneself or another person), (b) its primary direction or beneficiary (self or other), and (c) the status, in relation to oneself, of a relevant other person (for further discussion, see Meacham, 1988). For example, an intention to buy flowers for a visitor’s room may have low personal importance—unless the visitor happens to be your mother-in-law! In summary, it is clear that the intentional status or strength of a delayed intention will be strongly affected by the relations between that intention and other, longer term intentions, aims, and personal themes (see, e.g., Barsalou, 1988; Conway, 1992; Ortony, Clore, & Collins, 1988).

TABLE 1.1.

Examples of general (categorized) and specific retrieval contexts.

Type of Retrieval Context | General | Specific |

Event | A leisure period at work | The first coffee break |

Activity | Domestic work | Cleaning the bathroom |

Person | A secretary | Your personal secretary |

Object | A postbox | Your local postbox |

Time | In the morning | At 10:00 a.m. |

Location | A garage | The garage next to your office |

Finally, the retrieval context (or when-element) describes some characteristics of a future occasion that should prompt the retrieval of a delayed intention. Several potentially distinct types of context can be identified—events, activities, times, persons, objects, or locations (see, e.g., Einstein & McDaniel, 1990; Harris, 1984). The relationships between these retrieval context types are examined by Kvavilashvili and Ellis (this volume). A retrieval context that is defined in terms of only one of the above types is described as a pure retrieval context (e.g., telephone John at 10:00 a.m. [pure, time] or telephone Mary when you are in your office [pure, location]). A pure retrieval context may be either relatively general or categorized (e.g., a set of possible events or time period) or relatively specific (e.g., a particular event or particular time). Examples of both specific and general, pure retrieval contexts are provided in Table 1.1. Frequently however, for naturally occurring intentions at least, a retrieval context may be described in terms of more than one context type (e.g., an intention to see John at 10:00 a.m. before you go to a meeting refers to both a time and an event). These multiple-type or combined retrieval contexts can vary from the general to the specific.

Both pure and combined retrieval contexts may differ with respect to their opportuneness. This refers to the frequency with which a context occurs within a given performance interval (e.g., give Mary a message this morning when Mary usually enters your room several times during the morning), or number of performance intervals (e.g., give John a message this week when John comes into work on three mornings). The generality of a retrieval context may reflect, in some instances, the potential number of opportunities for performing an intended action. For example, an intention to telephone someone today may have a general retrieval context because one anticipates, at encoding, several potentially appropriate occasions during the day when a telephone will be readily available. Similarly, a specific retrieval context may reflect a restricted set of opportunities (e.g., you have several meetings that day). It is also possible, however, that multiple opportunities will be encoded in the form of separate specific retrieval contexts rather than a general one (Einstein, personal communication, February 18, 1995). The implications of these different distinctions for the outcome of a delayed intention are considered later in the discussion on retrieval.

Representation of Retrospective Component

Clearly the various elements outlined above, which together constitute the content of a delayed intended action, are not necessarily independent of one another. For example, the application of planning processes that are directed towards action- or what-realization may increase the strength of an intention, whereas the latter may influence the specificity of a retrieval context. How, though, are these elements related and represented within a cognitive system? In an action-trigger-schema (ATS) framework, developed by Norman (1981) and Norman and Shallice (1986) and extended by Rumelhart and Norman (1982), actions are represented by action schemas that at any given time have a level of activation together with trigger conditions. A schema is selected once its activation level exceeds a certain threshold and initiated once its trigger conditions have been satisfied. The activation value is important primarily in the selection of an action, and the extent of the match between existing conditions and an action’s trigger conditions influences the amount of activation received by that action. For example, Rumelhart and Norman suggested that a well-learned action sequence such as typing a word can be represented by a set of schemas. The occurrence of a perceptual event (e.g., the handwritten word), and processing of this event (by, e.g., a parser) activates the schema for that word which in turn activates subschemas for particular key presses. The perceptual event, together with other more specific conditions as appropriate, provides the trigger conditions for the initiation of the schema and the selection of the appropriate motor movements (see Rumelhart & Norman, 1982, for further details).

The retrieval context of a delayed intention can be seen as providing the trigger conditions for the future retrieval of its encoded action whereas its intentional status or strength might be expected to exert an influence on the activation level of that action. Activation (and inhibition) can spread to other related action + goal structures (schemas) which, in turn, may influence the intentional status and thus the activation level of the initial encoded action. Activation levels, however, are temporary and short-lived, and thus unlikely to reflect the more durable and pervasive aspects of many motivational states. It is suggested, therefore, that variations in intentional status are likely to be reflected in the threshold value associated with a particular action schema. This means of representing delayed intentions forms the basis of the conceptual framework that is elaborated in the following discussion.

The Prospective Component

This includes the elements described in phases Β through to E, described previously and illustrated in Fig. 1.1. It includes also other relevant events, such as recollections, that occur during either retention or performance intervals. The term reco...