![]()

Chapter One

Applied Generalizability Theory Models

George A. Marcoulides

California State University, Fullerton

Generalizability (G) theory is a statistical theory about the dependability of behavioral measurements (Shavelson & Webb, 1991). Although many psychometricians can be credited with paving the way for G theory (e.g., Burt, 1936, 1947; Hoyt, 1941; Lindquist, 1953), it was formally introduced by Cronbach and his associates (Cronbach, Gleser, Nanda, & Rajaratnam, 1972; Cronbach, Rajaratnam, & Gleser, 1963; Gleser, Cronbach, & Rajaratnam, 1965) as an extension of classical reliability theory. Since the major publication by Cronbach et al. (1972), G theory has gained increasing attention, as evidenced by the growing number of studies in the literature that apply it (Shavelson, Webb, & Burstein, 1986). The diversity of measurement problems that G theory can solve has developed concurrently with the frequency of its application (Marcoulides, 1989a). Some researchers have gone so far as to consider G theory “the most broadly defined psychometric model currently in existence” (Brennan, 1983, p. xiii). Clearly, the greatest contribution of G theory lies in its ability to model a remarkably wide array of measurement conditions through which a wealth of psychometric information can be obtained (Marcoulides, 1989c).

The purpose of this chapter is to review the major concepts in G theory and illustrate its use as a comprehensive method for designing, assessing, and improving the dependability of behavioral measurements. To gain a perspective from which to view the application of this measurement procedure and to provide a frame of reference, G theory is compared with the more traditionally used classical reliability theory. It is hoped, by providing a clear and understandable picture of G theory, that the practical applications of this technique will be adopted in business and management research. Generalizability theory most certainly deserves the serious attention of all researchers involved in measurement studies.

Overview of Classical Reliability Theory

Classical theory is the earliest theory of measurement and the foundation for many modern methods of reliability estimation (Cardinet, Tourneur, & Allai, 1976). Despite the development of the more comprehensive G theory, classical theory continues to have a strong influence among measurement practitioners today (Suen, 1990). In fact, many tests currently in existence provide psychometric information based on the classical approach. Classical theory assumes that when a test is administered to an individual the observed score is comprised of two components. The first component is the true underlying ability of the examinee, which is the intended target of the measurement procedure. The second component is some combination of unsystematic error in the measurement, which somehow clouds the estimate of the examinee’s true ability. This relationship can be symbolized as:

Observed score (X) = True score (T) + Error (E)

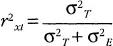

The better a test is at providing an accurate indication of an examinee’s ability, the more accurate the T component will be and the smaller the E component. Classical theory also provides a reliability coefficient that permits the estimation of the degree to which the T component is present in a measurement. The reliability coefficient is expressed as the ratio of the variance of true scores to the variance of observed scores and as the error variance decreases the reliability coefficient increases. Mathematically this relationship is expressed as:

or

The evaluation of the reliability of a measurement procedure is basically a question of determining how much of the variation in a set of observed scores is a result of the systematic differences among individuals and how much is the result of other sources of variation. Test–retest reliability estimates provide an indication of how consistently a test ranks examinees over time. This type of reliability requires administering a test on two different occasions and examining the correlation between the two test occasions to determine stability over time. Internal consistency is another method for estimating reliability and measures the degree to which individual items within a given test provide similar and consistent results about an examinee. Another method of estimating reliability involves administering two “parallel” forms of the same test at different times and examining the correlation between the forms.

The preceding methods for estimating reliabilities of measurements suggest that it is unclear which interpretation of error is the most appropriate. Obviously, the error variance estimates will vary according to the measurement designs used (i.e., test–retest, internal consistency, parallel forms), as will the estimates of reliability. Unfortunately, because classical theory provides only one definition of error, it is unclear how one should choose between these reliability estimates. Thus, in classical theory one often faces the uncomfortable fact that data obtained from the administration of the same test to the same individuals may yield three different reliability coefficients.

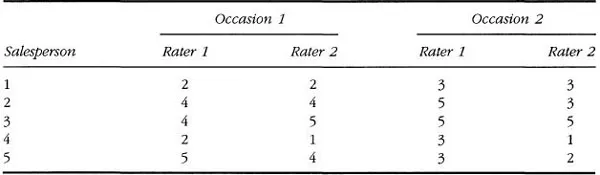

To make this discussion concrete, an example is in order. A personnel manager wishes to measure the job performance of five salespersons by using a simple rating form. The rating form covers such things as effective communication, effectiveness under stress, meeting deadlines, work judgments, planning and organization, and initiative. Two supervisors independently rate the salespersons in terms of their overall perfomance using the rating form on two occasions, with ratings from “not satisfactory” to “superior.” The ratings comprised a 5-point scale. Table 1.1 presents data from the hypothetical example.

Table 1.1 Data From Hypothetical Job Performance Example

Using the preceding data, how might classical theory calculate the reliability of these jobs performance measures? Obviously, with performance measurements taken on two different occasions, a test–retest reliability can be calculated. A test–retest reliability coefficient is calculated by correlating the salespersons’ scores from Occasion 1 with the scores from Occasion 2, after summing over all other information in the table. This value is approximately 0.73. Of course, an internal consistency reliability can also be calculated. This value is approximately 0.87. Thus, it appears that not only are the estimates of reliability in classical theory different, but they are not even estimates of the same quantity (Webb, Rowley, & Shavelson, 1988). Although classical test theory defines reliability as the ratio of the variance of true scores to the variance of observed scores, as evidenced by the earlier example, one is confronted with changing definitions of what constitutes true and error variance. For example, if one computes a test–retest reliability coefficient, then the day-to-day variation in the salespersons’ performance is counted as error, but the variation due to the sampling of items is not. On the other hand, if one computes an internal consistency reliability coefficient, the variation due to the sampling of dif...