Creating Critical Classrooms

Reading and Writing with an Edge

- 286 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Creating Critical Classrooms

Reading and Writing with an Edge

About this book

This popular text articulates a powerful theory of critical literacy—in all its complexity. Critical literacy practices encourage students to use language to question the everyday world, interrogate the relationship between language and power, analyze popular culture and media, understand how power relationships are socially constructed, and consider actions that can be taken to promote social justice. By providing both a model for critical literacy instruction and many examples of how critical practices can be enacted in daily school life in elementary and middle school classrooms, Creating Critical Classrooms meets a huge need for a practical, theoretically based text on this topic.

Pedagogical features in each chapter

• Teacher-researcher Vignette

• Theories that Inform Practice

• Critical Literacy Chart

• Thought Piece

• Invitations for Disruption

• Lingering Questions

New in the Second Edition

• End-of-chapter "Voices from the Field"

• More upper elementary-grade examples

• New text sets drawn from "Classroom Resources"

• Streamlined, restructured, revised, and updated throughout

• Expanded Companion Website now includes annotated Classroom Resources; Text Sets; Resources by Chapter; Invitations for Students; Literacy Strategies; Additional Resources

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Chapter 1

Overview

Vignette

Research Questions

- What causes food throwing? Is this a problem? What causes “no trash-backs?”

- What happens when people save seats? How many people save seats?

- What makes the lunchroom loud? What is too loud?

- How does a chain reaction happen? What is a chain reaction?

- What do people like about the lunchroom?

- What do people not like about this space?

What Is Critical Literacy?

| Personally Responsible Citizen | Participatory Citizen Description | Justice-Oriented Citizen |

|

|

|

| Sample Action | ||

| Contributes food to a food drive | Helps to organize a food drive | Explores why people are hungry and acts to solve root causes |

| Core Assumptions | ||

| To solve social problems and improve society, citizens must have good character; they must be honest, responsible, and law abiding members of the community. | To solve social problems and improve society, citizens must actively participate and take leadership positions within established systems and community structures. | To solve social problems and improve society, citizens must question, debate, and change established systems and structures when they reproduce patterns of injustice over time. |

The Role of Theory in Critical Practice

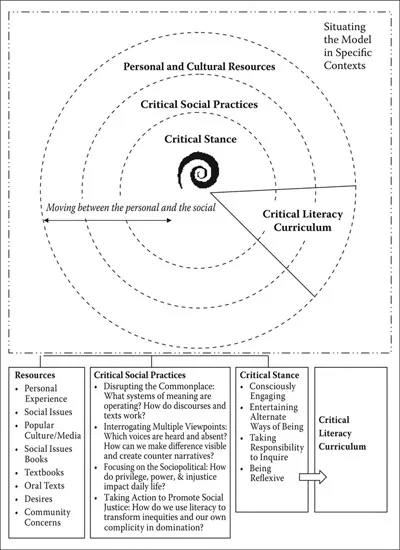

A Model of Critical Literacy Instruction

Personal and Cultural Resources

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Brief Contents

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword / Linda Christensen

- Introduction

- Chapter One / Overview: Why Do We Need an Instructional Theory of Critical Literacy?

- Chapter Two / Personal and Cultural Resources: Using Life Experiences as an Entrée into Critical Literacy

- Chapter Three / Cultural Resources: Using Popular Culture to Promote Critical Practice

- Chapter Four / Cultural Resources: Using Children’s and Young Adult Literature to Get Started with Critical Literacy

- Chapter Five / Critical Social Practices: Disrupting the Commonplace Through Critical Language Study

- Chapter Six / Critical Social Practices: Interrogating Multiple Perspectives

- Chapter Seven / Critical Social Practices: Focusing on the Sociopolitical

- Chapter Eight / Critical Social Practices: Taking Action to Promote Social Justice

- Chapter Nine / Taking a Critical Stance: Outgrowing Ourselves

- Chapter Ten / Invitations for Students

- Classroom Resources: Children’s Books, Videos, Songs, and Websites

- Appendix: Creating Critical Classrooms Companion Website Contents

- About the Authors

- References

- Index