- 252 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"The controversial works of Brazilian authors Silviano Santiago(1936-) and Caio Fernando Abreu (1948-96) offer distinctive but complementary explorations of male homosexual subjectivities formulated through displacement, exile and the abject. Posso examines the innovative ways in which these writers stage-manage Western poststructuralist thought to critique heterosexist exclusion in Brazil and in globalized popular and folk culture, and he explains how they draw on diverse cultural productions and art works to extend a general undermining of oppositional logic and psychoanalytic theory."

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Artful Seduction by Karl Posso in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Languages. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Ambiguous Art of Vanishing: Abjection and Undecidable Homosexuality in Stella Manhattan

Being, when questioned, slips into indecisiveness, turns into interference, splits apart—like laughter...1

GEORGES BATAILLE

Silviano Santiago's Stella Manhattan examines the construct of society along sexual and political axes: its two main events are the exile of the Brazilian protagonist as a result of his homosexuality, and a guerrilla raid on the Manhattan apartment of the Brazilian military attaché because of his fascist alliances. This chapter focuses on the social inscription of the homosexual as waste, as that which cannot be accommodated along either of the two axes and should therefore be expelled from the community, and in this case, from the narrative economy. Within this context it will be argued that the eventual disappearance of the problematic homosexual protagonist, not through exclusion, but through his own vanishing act, executes a surprising deconstruction of the illusion of heterosexist hegemony. The shattering of this illusion will be shown to accompany the loss of objectivity of the political discourses which seek to structure the narrative progression. The importance of New York, and in particular Manhattan, as the polyglot arena for these deconstructive anagnorises, emphasized by the protagonist's eponymous alter ego, is telling: the city as the symbolic point of intersection of all political, sexual and linguistic constructs indicates how all identities are produced and dissolved through multiple mediations; and as a metonym for globalized culture, the city enables the social critique elaborated in relation to a small Brazilian enclave to be read as universally applicable.

Gaming with History

Published in 1985 when the military administration finally fell, Stella Manhattan looks back to 1969, the year in which the leadership of the Brazilian authoritarian regime twice changed hands: General Artur da Costa e Silva, paralysed by a stroke, was replaced unconstitutionally on 31 August by the 'Junta Militar'—Aurélio de Lira Tavares (Army), Augusto Rademaker Grünewald (Navy) and Márcio de Sousa e Melo (Air Force); the triumvirate then made way for the most severe dictator in the country's history, Emílio Garrastazu Médici, who came to power on 30 October, 1969, therefore, marked the beginning of what have come to be known as the 'anos de chumbo' ['the lead years'], the brutal nadir of the military dictatorship. The fictitious episodes of the novel, which takes place over a two-day period beginning on 18 October, are intimately tied to these political vicissitudes and so blur boundaries between history and fabulation. The narrative progresses through mediation with references to the military's Gestapo-like hold on the nation—'[v]iolência violência violência. Sede. Fome. Solidão. Chutes, murros, socos, palmadas ensurdecedoras. Corpos lançados de avião em alto-mar'2 ['violence and more violence. Thirst, hunger, loneliness. Punches, kicks in the balls, deafening slaps over your ears. Then the corpses would be thrown from planes into the ocean'3]—and the confidences of guerrillas who have been released from prison in exchange for Charles Burke Elbrick, the American ambassador kidnapped in Brazil that year. These guerrillas are also said to be hoping to forge links with other revolutionary movements by infiltrating Leonard Bernstein's soirée for the Black Panthers and that of Ellie Guggenheim for the Young Lords, again fusing fiction and historical account.4

In playing with the boundaries of fact and fiction, the novel resists becoming a testimonial or 'memorialista' diatribe against the intensification of military oppression during this period, thus implying that history can never be objectified by any single discourse. Instead of perpetuating the dialectics which forever repeat the conditions that provoked revolt, the novel seeks to deconstruct both fascist ideology and the discourses of transgression which sought to debunk it by elaborating a general critique of oppositional logic. This critique is laboured through the reflection on the foundering of the sociopolitical ideals which proliferated during the late 1960s and early 1970s, both in reaction to the fascist regime, and in the case of homosexuality, as a consequence of the Stonewall riots, which precede the novel's action by just over three months. The pessimism with which the review of past dialectics is imbued, as Idelber Avelar has discussed in The Untimely Present, transforms the revisory process into a play with pastiche: historical signifiers are invested with the hindsight or signified of the present, here pessimism born of the knowledge of defeat of these ideals.5 This anachronistic sense of pessimism, or the incorporation of defeat, enables the novel to negotiate a critical continuum between the present view of the past and the past view of the present. This temporal fusion by way of differential (pessimistic) repetition of values through pastiche makes explicit the paradox of coexistence which Deleuze derives from Bergson: 'past and the present do not denote two successive moments, but two elements which coexist: one is the present, which does not cease to pass, and the other is the past, which does not cease to be but through which all presents pass'.6 The effect produced by the narrative's logic of coexistence through defeat is, as Avelar describes in relation to Santiago's Em liberdade [Free]: 'the uncanny feeling that the past is citing the future, in both senses of the verb: quoting it but at the same time summoning it to appear in court to be judged' (p. 160). In other words, the narrative gives the unsettling impression that the failed past is looking in despair at a future from which it will be judged a failure, but also, because of its relentless pessimism, that this past gazes onto a future of ongoing failure. What is being suggested, therefore, is that the analysis or deconstruction of this past failure necessarily implies a deconstruction of the authorial and readerly present (the narrative future) which is fused to the past by way of the notion of perpetual defeat. In Stella Manhattan these defeated but enduring principles are the oppositional modi operandi of autocracy, guerrilla movements and gay liberation discourses, which Santiago's narrative works to discredit through the ambiguous erasure of the object which ballasts their textual authority: the homosexual.

Hinged Ontology: Name and Character Dynamics

Before proceeding to the principal argument regarding the exclusion and eventual disappearance of the homosexual from the text, a summary of the plot will be necessary. This will be offered in the first part of the current section through the discussion of Santiago's use of nomenclature. The second half of the section will be devoted to an evaluation of the techniques of textual construction and characterization.

In an interview given in 1997, Santiago commented that in naming his characters he often uses 'a play on words... as they say in English, an in-joke, a pun which can only be appreciated by certain people'.7 This play with names is a particularly prominent feature of Stella Manhattan. The protagonist, Eduardo (alias Stella Manhattan and Bastiana), sent to work in the Brazilian consulate in New York by his parents upon discovering he is gay, shares the surname Costa e Silva with the deposed military dictator, mentioned earlier, who later died in 1969. Although this correlation becomes increasingly inappropriate, given Eduardo's political apathy and the progressive revelation of his ignorance of the military's machinations in Brazil, the surname, nevertheless, presages his eventual removal from or abdication of the narrative and the possibility of his demise thereafter. Similarly, the military attaché, Colonel Vianna, through whom Eduardo's father had arranged the job in New York, bears the first name Valdevinos, a word connoting both chivalry and wretchedness:8 an ambiguity which is fitting given the performance of noble paternalism with which he wins Eduardo over in order to exploit him. Vianna, unbeknown to most, precariously alternates public respectability as military attaché and devout Catholic husband with covert promiscuity as an insatiable gay sadomasochist, alias the 'Viúva Negra' ['Black Widow']. By persuading Eduardo to sign a lease for an apartment in a poor Manhattan neighbourhood, and obliging him to foist upon the estate agent the story of helping out some Brazilian student at Columbia University by paying for accommodation, Vianna procures an anonymous setting for his nocturnal undertakings. (Anonymity here is aided by the humorously pedestrian name invented for the non-existent student: Mário Correia Dias.) Subsequently, when guerrillas seeking to exact revenge on the Colonel—for previous work in Brazil as torturer for the military regime—vandalize the apartment, Eduardo is left to face FBI interrogations regarding the suspicion that communist guerrillas are behind the anti-fascist graffiti on the walls. Furthermore, as he is perceived to be Vianna's aide-de-camp, Eduardo himself becomes a prime target for the guerrillas. At very least, the guerrillas wish to use Eduardo as a vehicle for passing on false information to Vianna.

The Brazilian revolutionaries behind this operation are linked to Cuba and aim to expand the revolution in Latin America into the United States through coalitions with minority movements such as the Black Panther Party, the Young Lords and César Chávez's 'La Huelga' (Farm Workers Movement). One of the guerrillas is an allegedly bisexual, but most likely gay, Brazilian lecturer at New York University, Marcelo, who ends up betraying Eduardo by sleeping with Rickie, the rent boy on whom he had foolishly pinned hopes of emotional fulfilment. As he had been a friend of Eduardo at university in Rio de Janeiro, Marcelo is given the responsibility of enlisting Eduardo for the Leftist cause. However, when confronted with Eduardo's political insouciance, Marcelo's intransigence surfaces through the dogmatic inculcation of his Marxist doctrines, revealing an intolerance akin to that of the autocratic Brazilian regime he is fighting to overthrow The convergence of monolithic ideologies in this instance is emphasized by the guerrilla alias adopted by Marcelo, that is, the name Caetano. The juxtaposition of 'Marcelo' and 'Caetano' recalls the Portuguese minister of that name, also an academic, who stood in for Salazar between 1968 and 1974, and later died in exile in Brazil. Further similarities between the extreme Right and Left are established when Marcelo encounters the ultra-conservative Professor Aníbal. Again, the irony of the professor's name is highly suggestive: in marked contrast to the heroic Carthaginian who led the expedition across the Alps, Aníbal is confined to a wheelchair and is guarded by a profusion of bolts and locks which line his apartment door; his physical paralysis and reclusiveness mirror his compromised power as a stalwart of the Brazilian regime hypocritically exiled in the United States. Here, however, Santiago explicitly forestalls the formation of a structuralist code between name and character by stressing the ambiguity of such onomastic play: the image of Aníbal's ostensible political redundancy is later contested by his collaboration with the Brazilian Intelligence Service (SNI) and the FBI, in order to secure the successful capture and deportation of the revolutionaries involved in the raid on Vianna's apartment. Curiously, because Marcelo does not feature on the list given to the FBI, it appears that Aníbal reprieves him from the fate of the other guerrillas. Inasmuch as Marcelo, at least as an academic, is overt in his opposition to all forms of authoritarianism, Aníbal appears to see him as an objectification of the other justifying his intellectual career; hence the narrator's description of the two academics in terms of Tom and Jerry (p. 121) [p. 87]. Furthermore, because Marcelo's ideological inflexibility parallels that of Aníbal—the latter is described as an outright fascist, the former as a 'pequeno ditador vermelho' (p. 130) ['little red dictator' (p. 94)]—he unwittingly offers a solipsistic reaffirmation of totalitarianism.

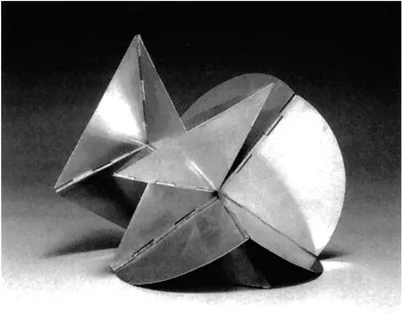

It is totalitarianism which leads to the discussion of textual construction and characterization: during the debate between Marcelo and Aníbal concerning a totalitarian or monolithic aesthetic, Marcelo argues in favour of a non-objectifying mode of artistic creation, delivering a meta-textual commentary on the nature of character construction in the novel. Marcelo is opposed to Aníbal's rigid artistic and linguistic ideals, exemplified by his sole childhood amusement, the imposition of semantic fascism via the eradication of polysemy and linguistic ambiguity. A young Aníbal and his friend Ricardo had delighted in literal interpretations of commonplace figurative expressions, for example: 'Vida de cachorro. Seres humanos que andam com as quatro patas no chão. Não conversam. Quando abrem a boca é pra latir [...] pessoas que só falam por monossílabos, au au au' (p. 162) ['A dog's life: human beings who walked around on all fours. They don't speak; when they open their mouths it's only to bark [...] people who speak only in monosyllables, bow, wow, wow' (p. 119)]. In contesting Aníbal, Marcelo refers to the authorial premises of textual production as a derivation of the fluid aesthetics of Lygia Clark and Hans Bellmer. This is later supported by a postscript to the novel, in which Santiago states that the 'hinge-like' configuration of the narrator and characters in Stella Manhattan is inspired by two sculptures: Lygia Clark's Bichos [Creatures] (Fig. 1) and Hans Bellmer's La Poupée [The Doll] (Figs. 2and 3). Marcelo compares Clark to Josef Albers, the Bauhaus artist best known for his series of paintings, Homage to the Square, which presents colours in quasi-concentric squares:

Gosto de Albers. Me lembra coisas de Lygia Clark. Só que, na sua série dos Bichos, Lygia foi mais longe, misturou a precisão geométrica de Albers com a sensualidade orgânica das bonecas de Bellmer. Albers ficou sempre nos jogos tridimensionais dentro da superfície bidimensional. Lygia descobriu a dobradiça que deixa as superfícies planas se movimentarem com a ajuda das mãos do espectador. Os olhos vêem depois para apreciar a combinação que foi conseguida. Que cada um conseguiu. [...] Lygia requer primeiro o tato do espectador, [...] só depois a visão. O sensualismo do contato do corpo com a obra de arte, do desejo com o objeto para poder melhor compreendêlo. O ideal é que a obra de arte seja consumida por todos os cinco sentidos ao mesmo tempo. (p. 127)

[I like Albers. His prints remind me of Lygia Clark's work. But I think Lygia went farther in her Creatures series, mixing Albers's geometric precision with the organic sensuality of Bellmer's dolls. Albers never got away from three-dimensional games on a two-dimensional surface. Lygia discovered the hinge-like duplicity that activates her flat surfaces with the viewer's aid.

Fig. 1. Lygia Clark, Bicho (1960/1962) Articulated aluminium segments 17 X 38 X 26 cm (variable dimensions) Malba/Colección Costantini, Buenos Aires, Argentina Associação Cultural 'O Mundo de Lygia Clark'

Afterward the eyes can appreciate the combinations that were achieved. That each participant achieved. [...] First of all, Lygia requires the viewer's touch [...] vision comes afterward. The sensualism of bodily contact with the work of art and of desire with its object make it more comprehensible. The ideal is for all five senses to consume the work of art simultaneously. (p. 92)]

The work of art that provokes the beholder into participation enables a continuum of desire which fuses subject and object, physically rendering the distinction between them obsolete. The articulated geometrical planes of the 'bicho' and the convulsive body of the doll, an undecidable Galatea of sorts, by inviting the onlooker to play with them, make him or her transcend the stasis of the contemplative subject/object relationship and therefore become part of the artistic process itself. The viewer's manipulation of the artefact and the artefacts response to this intervention through unpredictable hinged movements, seducing the viewer into further activity, results in a kinetic blurring of the subject and object binary. In the peroration to his meta-textual treatise on art, Marcelo alludes to...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of Illustrations

- Introduction Seductive Exclusion: The Fracture and Weakening of Heterosexism in Brazil

- 1 The Ambiguous Art of Vanishing: Abjection and Undecidable Homosexuality in Stella Manhattan

- 2 'Autumn Leaves': Deciduous Signification and Homosexual Exile

- 3 'Bem longe de Marienbad': The Masochistic Dislocation of Homosexual (Dis)satisfaction

- 4 'There's no place like home': Writing Off the Domus in Onde andará Dulce Veiga?

- Social Critique, Potential Communities

- Bibliography

- Index