- 1,142 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The English Literatures of America redefines colonial American literatures, sweeping from Newfoundland and Nova Scotia to the West Indies and Guiana. The book begins with the first colonization of the Americas and stretches beyond the Revolution to the early national period. Many texts are collected here for the first time; others are recognized masterpieces of the canon--both British and American--that can now be read in their Atlantic context. By emphasizing the culture of empire and by representing a transatlantic dialogue, The English Literatures ofAmerica allows a new way to understand colonial literature both in the United States and abroad.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The English Literatures of America by Myra Jehlen,Michael Warner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Collections. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

TWO

THE SIXTEENTH AND SEVENTEENTH CENTURIES

Chapter 2

Learning to Say “America” in English

INTRODUCTION

Like the Ming Chinese, the Ottoman Turks, the Spanish, and the Portuguese, the English at the close of the fifteenth century were showing interest in other lands. Cosmography became an arousing business. The transnational elite of cosmographers visited and corresponded with the Tudor court. Columbus, seeking backing for his route to India in the late 1480s, approached Henry VII as a likely source—though without success. The Cabota family left Venice for London, where the father and son would come to be known as John and Sebastian Cabot. Gradually the English began developing their own speculations about the navigable world. Expeditions went east, to Russia, looking for a northerly route to India. (Later, expeditions in the other direction would be financed by the same Muscovy Company.) They went overland to Persia, down the Atlantic coast to Africa, and, in the wake of the Spanish, to the tropics of the Western hemisphere. The English paid more attention than before to neighboring Atlantic islands, dramatically renewing efforts to dominate the Irish. They also began speculating about the more distant northwest lands where English boats had already been visiting on fishing expeditions. Could they find a route to India that way?

Still, throughout the sixteenth century, and well into the seventeenth, English efforts in the Western reaches of the Atlantic were tentative and feeble by comparison with the Spanish and Portuguese empires. With the wealthiest of the Amerindian cultures already enslaved, the English found little prospect in imitating the Iberian model of conquest. Even later, when they applied the classic model of colonialism on a grand scale in India, they did not do so in the Americas. As the texts collected here show, however, the English slowly developed in the Western hemisphere a different kind of colonial venture. Instead of sending an armed administration to control the wealth of a native population, the English began to consider sending their own population—something the Spanish and Portuguese never willingly did. The settlement method of colonialism, called “planting,” was a new game entirely. It allowed the English finally to get out from under the Iberian shadow in the competition of empires.

This chapter covers the first phase of English expansion, when the new model of settlement colonies was still only a theory. The texts are not limited, therefore, to what would later become English colonies, for English interests before settlement were geographically rather vague. To the end of the century, English speculation continued to center on India and China. Because the English had not yet set up a territorial administration, they tended to use geographical names loosely: India, Cathay, Newfoundland, Virginia, America, New Albion, New Spain, and Terra Florida are overlapping if not interchangeable terms in many of these texts.

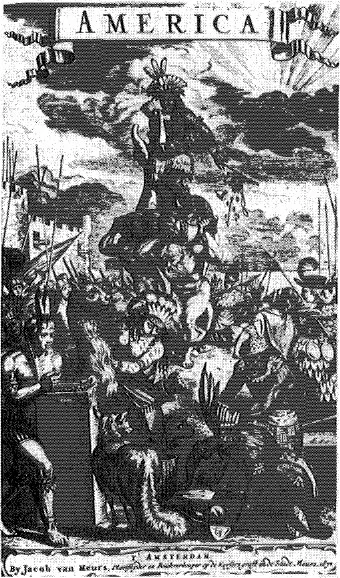

“America” Amsterdam, 1671.

The writings collected here, unlike their French or Spanish counterparts, show only sporadic interest in Amerindians. English writing contains no equivalent of Sahagun, Las Casas, or the Jesuit Relations. These texts should not therefore be regarded as an encompassing record of the period. They are what the English themselves produced as their record. Written texts themselves, during the period covered here, were central to the growing self-understanding of the English as a nation and as an empire. The English were not yet developing colonies, but they were developing a record—written reports that they could circulate as part of a developing culture of cosmo-graphical alertness. London printers gradually became involved in marketing the new expertise. They published narratives, polemics, tributes, and—not least—translations of the most informative French and Spanish works. The summa of this great enterprise was Richard Hakluyt’s great compilation, The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques, and Discoveries of the English Nation. Many of the texts in this chapter appeared in Hakluyt, though only about half of his collection was devoted to the Americas. Hakluyt does not seem to have intended a thorough documentation of the New World; his focus was on English forays outward, and his industrious editing indeed demonstrated the long reach of English envoys, in all parts of the known world. He himself also advanced some of the earliest theories for the English-American colonial mode.

Selections appear in a rough chronology; we seek to introduce readers to a public discussion as it developed. Some Englishmen would have known of nonEnglish writings, such as those of Columbus, which for a very long time went untranslated. An English reader might have known such works either because he (or, occasionally, she) knew the languages of the Continent; or because many such texts circulated in Latin, the transnational language of learning. A striking example of the latter is Utopia, written by the Englishman Thomas More, but not published in English in his lifetime. In it, a character refers to books about the New World as being “in print and abroad in every man’s hands”—even though More was writing in 1515, when no books about the New World yet existed in English. This chapter traces the growth of a vernacular literature, but it should be remembered that there were other kinds as well.

The English vernacular itself underwent enormous changes in the period covered by this chapter. Richard Hakluyt (and his compositors) routinely modernized the texts he collected at the end of the sixteenth century; in many cases his patterns of English usage remain current (-ly endings replace -lie, for instance). Early sixteenth-century texts looked archaic to him; they look even more so now. Those that pose the greatest challenge to modern readers we have given in both the original form and a modernized version. For other difficult texts we have modernized some spelling and punctuation. In the later and more substantial texts, especially Hariot, we have preserved the historical form of the texts as much as possible.

M.W.

Suggested readings: Samuel Eliot Morison, The European Discovery of America; Howard Mumford Jones, O Strange New World; Wayne Franklin, Discoverers, Explorers, Settlers.

1.

from The Great Chronicle of London

1502

Native Americans lived in England before the English lived in America. Like Columbus before him, John Cabot kidnapped natives and brought them back to court. Little else is known about these three Micmac Indians who thus found themselves in London, far from the place that was not yet known as America.

Thys yere alsoo were browgth unto the kyng iii men takyn In the Newe Found Ile land, that beffore I spak of In Wylliam Purchas tyme beyng mayer, These were clothid In beastis skynnys and ete Rawe Flesh and spak such spech that noo man cowde undyrstand theym, and In theyr demeanure lyke to bruyt bestis whom the kyng kept a tyme afftyr. Of whych upon ii yeris passid afftyr I sawe ii of theym apparaylyd afftyr Inglysh men In Westmynstyr paleys, which at that tyme I cowde not dyscern From Inglysh men tyll I was lernyd what men they were, But as For spech I hard noon of theym uttyr oon word.

[A MODERN PARAPHRASE]

This year also were brought unto the King three men, taken in the New-Found Island that before I spoke of, in William Purchase’s time as mayor. They were clothed in beasts’ skins, and ate raw flesh, and spoke such speech that no man could understand them. In their demeanor, they were like brute beasts. The King kept them a time after. After two years passed I saw two of them apparelled in the manner of Englishmen in Westminster Palace; at that time I could not tell them from Englishmen until I was told who they were. But as for speech I heard none of them utter one word.

2.

the first printed account of America in English

1511

The word “America” makes its first English appearance in 1509, as a passing reference in the translation of Sebastian Brandt’s The Ship of Fools (orig. 1494). The following account is based on a German broadside (a single printed sheet, like a poster) of 1505. It reveals as much about European fantasy as it does about the peoples of the Western hemisphere.

That lande is not nowe knowen for there have no masters wryten thereof nor it knowethe and it is named Armenica. there we sawe meny wonders of beestes and fowles yat we have never seen before, the people of this lande have no kynge nor lorde nor theyr god. But all thinges is comune … the men and women have on theyr heed necke Armes Knees and fete all with feders bounden for their bewtynes and fayrenes. These folke lyven lyke bestes without any resenablenes…. And they ete also on a nother. the man etethe hys wyfe his chylderne as we also have seen and they hange also the bodyes or persons fleeshe in the smoke as men do with us swynes fleshe. And that lande is ryght full of folke for they lyve commonly. iii.C. yere and more as with sykenesse they dye nat. they take much fysshe for they can goen under the water and feche so the fysshes out of the water, and theywerre also on upon a nother. for the olde men brynge the yonge men thereto that they gather a great company thereto of towe partyes and come the on ayene the other to the felde or bateyll and slee on the other with great hepes. And nowe holdeth the fylde they take the other prysoners. And they brynge them to deth and ete them and as the deed is eten then fley they the rest. And they been than eten also or otherwyse lyve they longer tymes and many yeres more than other people for they have costely spyces and rotes where they them selfe recover with and hele them as they be seke.

[A MODERN PARAPHRASE]

That land is not yet known, for no authorities have written about it nor known about it; and it is named America. There we saw many wonders, of beasts and fowles that we have never seen before. The people of this land have no king, nor lord, nor their god. All things are shared in common. The men and women have bound feathers on their head, neck, arms, knees, and feet, all for their beauty and fairness. These folk live like beasts without any reason. And they also eat one another. The man eateth his wife, and his children as we also have seen. They also hang the bodies or persons’ flesh in the smoke as men with us do swine’s flesh. And that land is very full of people, for they live commonly 300 years and more, as with sickness they die not. They take much fish, for they can go under the water and fetch the fishes out of the water. And they war also one upon another. For the old men bring the young men, gather a great company in two parties, and come the one against the other on the field or battle, and slay one another with great heaps. And now they who hold the field take the others prisoner. And they put them to death and eat them, and when the dead are eaten then they flay the rest. And they are then eaten also, or otherwise they live longer times and many years more than other people, for they have costly spices and roots with which they recover themselves and heal them that are sick.

This German woodcut, 1505, was the source of the first printed account of America in English.

3. Sir Thomas More

from Utopia

1516

More (1478–1535...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- GENERAL INTRODUCTION

- ONE: THE GLOBE AT 1500

- TWO: THE SIXTEENTH AND SEVENTEENTH CENTURIES

- THREE: THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

- INDEX