eBook - ePub

Reproductive Physiology and Birth Control

The Writings of Charles Knowlton and Annie Besant

- 218 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Reproductive Physiology and Birth Control

The Writings of Charles Knowlton and Annie Besant

About this book

"I say that this is a dirty, filthy book, and the test of it is that no human being would allow that book on his table, no decently educated English husband would allow even his wife to have ità." Such was the uncompromising pronouncement of Sir Hardinge Gifford, Her Majesty's Solicitor General, who in 1877 prosecuted Charles Bradlaugh and Annie Besant for publishing Dr. Charles Knowlton's Fruits of Philosophy.Knowlton's work was the first American medical handbook on contraception. It had become an incredibly popular book among Britons who believed the neo-Malthusian dictum that the only solution to poverty in Britain was a limit on the growth of its population. They saw effective birth control measures as a way to make such a limit practicable. In 1877, its publisher was hauled into court and pleaded guilty to printing obscene material. Bradlaugh and Besant tested the right of official harassment by bringing out an edition of the Fruits of Philosophy that bore an introduction explaining their motives. The pair was arrested and charged with violating the Obscene Publications Act of 1857.Their arrest, trial, conviction, and eventual acquittal constitute a landmark in the history of the world birth control movement. The enormous publicity accorded the principals and their cause brought the subject of family planning into the homes of nearly every Briton who read the newspapers' sensational coverage. What followed thereafter is telling: a dramatic, steady decline in the English birthrate. By their simple act of publishing Knowlton's short book, Bradlaugh and Besant helped establish England's pioneering role in the dissemination, democratization, and implementation of birth control information.Sripati Chandrasekhar is an internationally respected demographer and social scientist. He is a former minister of health and family planning in India and was vice-chancellor of Annamalai University in South India. He is the author of numerous books and articles on population and family planning.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Reproductive Physiology and Birth Control by S. Chandrasekhar in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Medical Theory, Practice & Reference. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The Texts

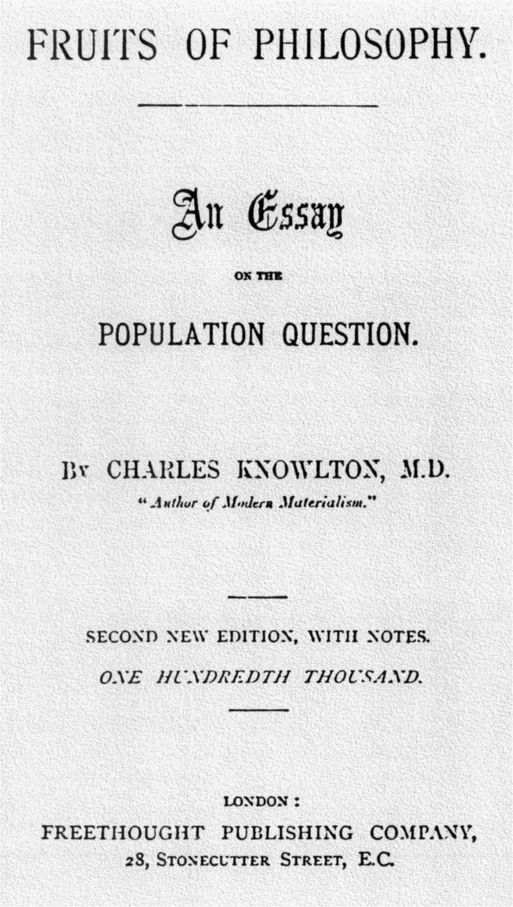

PUBLISHERS’ PREFACE

THE pamphlet which we now present to the public is one which has been lately prosecuted under Lord Campbell’s Act, and which we republish in order to test the right of publication. It was originally written by Charles Knowlton, M.D., an American physician, whose degree entitles him to be heard with respect on a medical question. It is openly sold and widely circulated in America at the present time. It was first published in England, about forty years ago, by James Watson, the gallant Radical who came to London and took up Richard Carlile’s work when Carlile was in jail. He sold it unchallenged for many years, approved it, and recommended it. It was printed and published by Messrs. Holyoake and Co., and found its place, with other works of a similar character, in their “Freethought Directory” of 1853, and was thus identified with Freethought literature at the then leading Freethought depot. Mr. Austin Holyoake, working in conjunction with Mr. Bradlaugh at the National Reformer office, Johnson’s Court, printed and published it in his turn, and this well-known Freethought advocate, in his “Large or Small Families,” selected this pamphlet, together with R. D. Owen’s “Moral Physiology” and the “Elements of Social Science,” for special recommendation. Mr. Charles Watts, succeeding to Mr. Austin Holyoake’s business, continued the sale, and when Mr. Watson died in 1875, he bought the plates of the work (with others) from Mrs. Watson, and continued to advertise and to sell it until December 23, 1876. For the last forty years the book has thus been identified with Freethought, advertised by leading Freethinkers, published under the sanction of their names, and sold in the head-quarters of Freethought literature. If during this long period the party has thus—without one word of protest— circulated an indecent work, the less we talk about Freethought morality the better; the work has been largely sold, and if leading Freethinkers have sold it—profiting by the sale—in mere carelessness, few words could be strong enough to brand the indifference which thus scattered obscenity broadcast over the land. The pamphlet has been withdrawn from circulation in consequence of the prosecution instituted against Mr. Charles Watts, but the question of its legality or illegality has not been tried; a plea of “Guilty” was put in by the publisher, and the book, therefore, was not examined, nor was any judgment passed upon it; no jury registered a verdict, and the judge stated that he had not read the work.

We republish this pamphlet, honestly believing that on all questions affecting the happiness of the people whether they be theological, political, or social, fullest right of free discussion ought to be maintained at all hazards. We do not personally endorse all that Dr. Knowlton says: his “Philosophical Proem” seems to us full of philosophical mistakes, and—as we are neither of us doctors—we are not prepared to endorse his medical views; but since progress can only be made through discussion, and no discussion is possible where differing opinions are suppressed, we claim the right to publish all opinions, so that the public, enabled to see all sides of a question, may have the materials for forming a sound judgment.

The alterations made are very slight; the book was badly printed, and errors of spelling and a few clumsy grammatical expressions have been corrected: the subtitle has been changed, and in one case four lines have been omitted, because they are repeated word for word further on. We have, however, made some additions to the pamphlet, which are in all cases kept distinct from the original text. Physiology has made great strides during the past forty years, and not considering it right to circulate erroneous physiology, we submitted the pamphlet to a doctor in whose accurate knowledge we have the fullest confidence, and who is widely known in all parts of the world as the author of the “Elements of Social Science;” the notes signed “G. R.” are written by this gentleman.* References to other works are given in foot-notes for the assistance of the reader, if he desires to study the subject further.

Old Radicals will remember that Richard Carlile published a work entitled “Every Woman’s Book,” which deals with the same subject, and advocates the same object, as Dr. Knowlton’s pamphlet. R. D. Owen objected to the “style and tone” of Carlile’s “Every Woman’s Book” as not being “in good taste,” and he wrote his “Moral Physiology,” to do in America what Carlile’s work was intended to do in England. This work of Carlile’s was stigmatised as “indecent” and “immoral,” because it advocated, as does Dr. Knowlton’s, the use of preventive checks to population. In striving to carry on Carlile’s work, we cannot expect to escape Carlile’s reproach, but whether applauded or condemned we mean to carry it on, socially as well as politically and theologically.

We believe, with the Rev. Mr. Malthus, that population has a tendency to increase faster than the means of existence, and that some checks must therefore exercise control over population; the checks now exercised are semistarvation and preventible disease; the enormous mortality among the infants of the poor is one of the checks which now keeps down the population. The checks that ought to control population are scientific, and it is these which we advocate. We think it more moral to prevent the conception of children, than, after they are born, to murder them by want of food, air, and clothing. We advocate scientific checks to population, because, so long as poor men have large families, pauperism is a necessity, and from pauperism grow crime and disease. The wage which would support the parents and two or three children in comfort and decency is utterly insufficient to maintain a family of twelve or fourteen, and we consider it a crime to bring into the world human beings doomed to misery or to premature death. It is not only the hard-working classes which are concerned in this question. The poor curate, the struggling man of business, the young professional man, are often made wretched for life by their inordinately large families, and their years are passed in one long battle to live; meanwhile the woman’s health is sacrificed and her life embittered from the same cause. To all of these, we point the way of relief and of happiness; for the sake of these we publish what others fear to issue, and we do it, confident that if we fail the first time, we shall succeed at last, and that the English public will not permit the authorities to stifle a discussion of the most important social question which can influence a nation’s welfare.

CHARLES BRADLAUGH

ANNIE BESANT

ANNIE BESANT

[*G. R. (George Rex, a nickname) stands for Dr. George Drysdah (1825-1904), Scottish physician, ardent Neo-Malthusian, author of a popu lar and long-selling tome of the period, The Elements of Social Science; the Physical, Sexual and Natural Religion (1887). S. C]

PREFACE TO SECOND NEW EDITION

WE Were not aware, when we published the first edition, that the editions published by James Watson, and professing to be reprinted by Holyoake and Co., Austin and Co., F. Farrah, J. Brooks, and Charles Watts, contained any variations. These variations are all of the most unimportant character, but as it was the edition issued by Mr. Watts, which was prosecuted, and as on careful reading we find there are some slight differences, the present edition is reprinted from his, with the exception of errors in printing and grammar.

CHARLES BRADLAUGH

ANNIE BESANT

ANNIE BESANT

PREFACE

By One of the Former Publishers

IT IS a notorious fact that the families of the married often increase beyond what a regard for the young beings coming into existence, or the happiness of those who gave them birth, would dictate; and philanthropists, of first-rate moral character, in different parts of the world, have for years been endeavouring to obtain and disseminate a knowledge of means whereby men and women may refrain at will from becoming parents, without even a partial sacrifice of the pleasure which attends the gratification of their productive instinct. But no satisfactory means of fulfilling this object were discovered until the subject received the attention of a physician, who had devoted years to the investigation of the most recondite phenomena of the human system, as well as to chemistry. The idea occurred to him of destroying the fecundating property of the sperm by chemical agents; and upon this principle he devised “checks,” which reason alone would convince us must be effectual, and which have been proved to be so by actual experience.

This work, besides conveying a knowledge of these and other checks, treats of Generation, Sterility, Impotency, &c. &c. It is written in plain, yet chaste style. The great utility of such a work as this, especially to the poor, is ample apology, if apology be needed, for its publication.

Philosophical Proem

CONSCIOUSNESS is not a “principle” or substance of any kind; nor is it, strictly speaking, a property of any substance or being. It is a peculiar action of the nervous system; and the nervous system is said to be sensible, or to possess the property of sensibility, because those sentient actions which constitute our different consciousnesses, may be excited in it. The nervous system includes not only the brain and spinal marrow, but numerous soft white cords, called nerves, which extend from the brain and spinal marrow to every part of the body in which a sensation can be excited.

A sensation is a sentient action of a nerve and the brain; a thought or idea (both the same thing) is a sentient action of the brain alone. A sensation, or a thought, is consciousness, and there is no consciousness but that which consists either in a sensation or a thought.

Agreeable consciousness constitutes what we call happiness, and disagreeable consciousness constitutes misery. As sensations are a higher degree of consciousness than mere thoughts, it follows, that agreeable sensations constitute a more exquisite happiness than agreeable thoughts. That portion of happiness which consists in agreeable sensations is commonly called pleasure. No thoughts are agreeable except those which were originally excited by, or have been associated with, agreeable sensations. Hence if a person never had experienced any agreeable sensations, he could have no agreeable thoughts; and would of course be an entire stranger to happiness.

There are five species of sensation, seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, and feeling. There are many varieties of feeling—as the feeling of hunger, thirst, cold, hardness, &c. Many of these feelings are excited by agents that act upon the exterior of the body, such as solid substances of every kind, heat, and various chemical irritants. Other feelings owe their existence to states or conditions of internal organs. These latter feelings are called passions.

Those passions which owe their existence chiefly to the state of the brain, or to causes acting directly upon the brain, are called the moral passions. They are grief, anger, love, &c. They consist of sentient actions which commence in the brain and extend to the nerves in the region of the stomach, heart, &c. But when the cause of the internal feeling or passion is seated in some organ remote from the brain, as in the stomach, the genital organs, &c, the sentient action which constitutes the passion, commences in the nerves of such organ, and extends to the brain; and the passion is called an appetite, instinct or desire. Some of these passions are natural, as hunger, thirst, the reproductive instinct, the desire to urinate, &c. Others are gradually acquired by habit. A hankering for stimulants, as spirits, opium and tobacco, is one of these.

Such is the nature of things that our most vivid and agreeable sensations cannot be excited under all circumstances, nor beyond a certain extent under any circumstances, without giving rise, in one way or another, to an amount of disagreeable consciousness, or misery, exceeding the amount of agreeable consciousness, which attend such ill-timed or excessive gratification. To excite agreeable sensations to a degree not exceeding this certain extent, is temperance; to excite them beyond this extent, is intemperance; not to excite them at all is mortification or abstinence. This certain extent varies with different individuals, according to their several circumstances, so that what would be temperance in one person may be intemperance in another.

To be free from disagreeable consciousness, is to be in a state which compared with a state of misery, is a happy state; yet absolute happiness does not consist in the absence of misery—if it do, rocks are happy. It consists, as aforesaid, in agreeable consciousness. That which enables a person to excite or maintain agreeable consciousness, is not happiness; but the idea of having such in one’s possession is agreeable, and of course is a portion of happiness. Health and wealth go far in enabling a person to excite and maintain agreeable consciousness.

That which gives rise to agreeable consciousness is good, and we desire it. If we use it intemperately, such use is bad, but the thing itself is still good. Those acts (and intentions are acts of that part of man which intends) of human beings which tend to the promotion of happiness are good; but they are also called virtuous, to distinguish them from other things of the same tendency. There is nothing for the word virtue to signify but virtuous actions. Sin signifies nothing but sinful actions: and sinful, wicked, vicious, or bad actions, are those which are productive of more misery than happiness.

When an individual gratifies any of his instincts in a temperate degree, he adds an item to the sum total of human happiness, and causes the amount of human happiness to exceed the amount of misery, farther than if he had not enjoyed himself, therefore it is virtuous, or, to say the least, it is not vicious or sinful for him so to do. But it must ever be remembered, that this temperate degree depends on circumstances—that one person’s health, pecuniary circumstances, or social relations may be such that it would cause more misery than happiness for him to do an act which, being done by a person under different circumstances, would cause more happiness than misery. Therefore it would be right for the latter to perform such act, but not for the former.

Again. Owing to his ignorance, a man may not be able to gratify a desire without causing misery (wherefore it would be wrong for him to do it), but with knowledge of means to prevent this misery, he may so gratify it that more pleasure than pain will be the result of the act, in which case the act to say the least is justifiable. Now, therefore, it is virtuous, nay, it is the duty for him who has a knowledge of such means, to convey it to those who have it not; for, by so doing, he furthers the cause of human happiness.

Man by nature is endowed with the talent of devising means to remedy or prevent the evils that are liable to arise from gratifying our appetites; and it is as much the duty of the physician to inform mankind of the means of preventing the evils that are liable to arise from gratifying the reproductive instinct, as it is to inform them how to keep clear of the gout or the dyspepsia. Let not the cold ascetic say we ought not to gratify our appetites any farther than is necessary to maintain health, and to perpetuate the species. Mankind will not so abstain, and if means to prevent the evils that may arise from a farther gratification can be devised, they need not. Heaven has not only given us the capacity of greater enjoyment, but the talent of devising means to prevent the evils that are liable to arise therefrom; and it becomes us, “with thanksgiving, to make the most of them.”

chapter 1

Showing how desirable it is, both in a political and a social point of view, for mankind to be able to limit, at will, the number of their offspring, without sacrificing the pleasure that attends the gratification of the reproductive instinct

FIRST.—In a political point of view.—If population be not restrained by some great physical calamity, such as we have reason to hope will not hereafter be visited upon the children of men, or by some moral restraint, the time will come when the earth cannot support its inhabitants. Population, unrestrained, will double three times in a century. Heitce, computing the present population of the earth at 1,000 millions, there would be at the end of the 100 years from the present time, 8,000 millions.

- At the end of 200 years 64,000 millions.

- At the end of 300 years 512,000 millions.

And so on, multiplying by eight for every additional hundred years. So that in 500 years from the present time, there would be thirty-two thousand seven-hundred and sixty-eight times as many inhabitants as at present. If the natural increase should go on without check for 1,500 years, one single pair would increase to more than thirty-five thousand one hundred and eighty-four times as many as the present population of the whole earth!

Some check, then, there must be, or the time will come when millions will be born but to suffer and to perish for the necessaries of life. To what an inconceivable amount of human misery would such a state of things give rise! And must we say that vice, war, pestilence, and famine are desirable to prevent it? Must the friends of temperance and domestic happiness stay their efforts? Must peace societies excite to war and bloodshed? Must the physician cease to investigate the nature of contagion, and to search for the means of destroying its baneful influence? Must he that becomes diseased be marked as a victim to die for the public good, without the privilege of making an effort to restore him to health? And in case of a failure of crops in one part of the world, must the other parts withhold the means of supporting life, that the far greater evil of excessive population throughout the globe may be prevented? Can there be no effectual moral restraint, attended with far less human misery than such physical calamities as these? Most surely there can. But what is it? Malthus, an English writer on the subject of population, gives us none but celibacy to a late age. But how foolish it is to suppose that men and women will become as monks and nuns during the very holiday of their existence, and abjure during the fairest years of life the nearest and dearest of social relations, to avert a catastrophe, which they, and perhaps their children, will not live to witness. But, besides being ineffectual, or if effectual, requiring a great sacrifice of enjoyment, this restraint is highly objectionable on the score of its demoralising tendency. It would give rise to a frightful increase of prostitution, of intemperance and onanism, and prove destructive to health and moral feelings. In spite of preaching, human nature will ever remain the same; and that restraint which forbids the gratification of the reproductive instinct, will avail but little with the mass of mankind. The checks to be hereafter mentioned, are the only moral restraints to population known to the writer, that are unattended with serious objections.

Besides starva...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- The Life and Work of Knowlton and His Fruits of Philosophy

- The Bradlaugh-Besant Trial 1877-1878

- The Writings of Annie Besant

- Appendix:NOTES ON INDIVIDUALS AND TERMS

- Bibliography

- The Texts

- Index of Names

- Index of Subjects