Chapter 1

Assessment Centers in Human Resource Management

The assessment center method is a procedure used by human resource management (HRM) to evaluate and develop personnel in terms of attributes or abilities relevant to organizational effectiveness. Even though all assessment centers share common features, the process can be adapted in many ways to achieve different objectives. The theme of this book is that each assessment center must be tailor-made to fit particular HRM purposes. The use of assessment centers for three human resource purposes will be analyzed in detail: (a) deciding who to select or promote, (b) diagnosing strengths and weaknesses in work-related skills as a prelude to development, and (c) developing job-relevant skills. The human resource manager must design the assessment center with a specific purpose in mind and then make choices to build an assessment center that adequately serves that purpose. Throughout this book, alternative ways of setting up each element of the assessment center are discussed, and a rationale for deciding what procedures to follow is provided. Recommendations for assessment center practice are based on theory and research relevant to each element of an assessment center, as well as the experience of many assessment center practitioners.

In this chapter we describe the assessment center method and compare it with other assessment procedures. Then we briefly describe several human resource functions and show how assessment centers have been used to facilitate these functions. In chapter 2 we present three cases that show how assessment centers are used to solve three very different types of HRM problems.

CONTINUITY AND CHANGE

We have seen both continuity and change over the last several decades in assessment center applications. Assessment centers are being used for a broader variety of purposes than they have in the past, and technological advances in assessment and development are being incorporated into the method in new and exciting ways. In addition, changes in the nature of work and organizations have called for changes in the way human resource functions are carried out. We describe these changes in more detail later in the chapter and throughout the book. However, to begin our discussion of the assessment center method, we start with what has remained constant throughout history: the basic assessment center method.

An essential feature of the assessment center method is the use of simulation exercises to observe specific behaviors of the participants (International Task Force, 2000). Also referred to as simulations, these exercises can involve, for example, situations requiring participants to prepare a written report after analyzing a marketing problem, make an oral presentation, answer mail and memos in an in-box, or talk with a customer about a service complaint. In addition to individual exercises, group exercises are often used if group interactions are a part of the target job. Such exercises could involve a situation where several participants are observed discussing an organizational problem or making business decisions. Trained assessors observe the behaviors displayed in the exercises and make independent evaluations of what they have seen. These multiple sources of information are integrated in a discussion among assessors or in a statistical formula. The result of this integration is usually an evaluation of each participant’s strengths and weaknesses on the attributes being studied and, in some applications, a final overall assessment rating. When assessment centers are used for development, individuals and groups can learn new management skills. We describe the effectiveness of assessment centers for these different uses later in this chapter. However, in order to understand the uses of assessment centers in modern organizations as well as the evolution of the assessment center method over time, it is necessary to understand the changing nature of work, workers, and organizations.

THE CHANGING NATURE OF WORK, ORGANIZATIONS, AND THE GLOBAL BUSINESS ENVIRONMENT

There are amultitude of changes occurring within and around the world of work. First, the job market is growing significantly, with 168 million jobs anticipated to make up the United States economy over the next 6 years (U. S. Department of Labor, 2003).

Second, the composition of the labor market is changing. The workforce will be made up of ever increasing percentages of minorities and women (Triandis, Kurowski, & Gelfand, 1993), many of whom will be entering nontraditional occupations. Research conducted in the United States has documented the special challenges women and minorities face when in roles more stereotypically “male” (Eagly, Makhijani, & Klonsky, 1992; Heilman, Wallen, Fuchs, & Tamkins, 2004) or “White” (Cheng, 1997; Tomkiewicz, Brenner, & Adeyemi-Bello, 1998) in nature. Human resource policies are needed to guard against potential biases that might occur in such situations, as well as the lowered job satisfaction and retention that might exist among these potentially marginalized groups (e.g., Burke & McKeen, 1996).

Third, there are changes occurring in the way in which organizations manage themselves. Many modern organizations are structuring jobs in order to create “high-performance work systems” that maximize the alignment between social and technical systems. Related to organizational changes are changes in how jobs are designed. Boundaries between jobs are becoming more and more “fuzzy” as organizational structures become more team-based and business becomes increasingly global (Cascio, 2002; Howard, 1995). Fourth, “knowledge workers” (i.e., individuals with very specialized knowledge) make up nearly half of current and projected job growth. The use of contingent workers continues to rise, in addition to the use of flexible work schedules to accommodate the complexities of employees’ personal lives (U.S. Department of Labor, 2001, 2002). Fifth, the world of work has seen amarked change in the implicit work contracts formed between employees and employers. Expectations of life employment have been replaced with expectations of shorter term employment. Whereas employers once took responsibility for the career development of employees, organizational cultures have shifted this responsibility to individuals who now form much shorter term implicit contracts with their employing organizations (Cascio, 2002). These changes call for innovations in HRM generally, and in assessment and development practices specifically.

THE IMPORTANCE OF CAREFULLY CONSTRUCTED HUMAN RESOURCE “TOOLS”

So what do all of these changes mean for the management of human resources? First, the increases in the labor pool, coupled with the changing nature of the employee–employer implicit contract, puts additional pressure on HRM to develop tools that will best enable organizations to recruit, select, train, and retain the very best talent available. Because of the increased diversity within the workforce and the importance of complying with various employment laws, it is necessary that these tools are both per-ceived as fair by applicants and employees, and actually are fair, that is, free of various forms of bias. Indeed, research shows that in the United States, women and minorities continue to be promoted at lower rates than their male, Anglo counterparts (Cheng, 1997; Lyness & Judiesch, 1999; Rober-son & Block, 2001). This places a special challenge on human resource professionals to create assessment and decision-making tools that “level the playing field” for these various groups.

The changing nature of the jobs themselves creates additional challenges. For one, organizations must be able to measure the attributes necessary for success in these evolving jobs. Such attributes include adaptability, acculturation, readiness and motivation to learn, and other skills that are difficult to define, measure, and develop. Last, the globalization of business and the technological advances that have made remote business possible have created business structures requiring human resource tools that are also remote, portable, flexible, and secure. In sum, changes in the organizational environment have altered the needs for various human resource management tools and the attitudes of applicants and employees about such tools. There is a great need for organizations to take much care in developing, validating, and administering HRM practices, using the best tools to achieve their goals.

THE ASSESSMENT CENTER METHOD

The assessment center method offers a comprehensive and flexible tool to assess and develop applicants and employees in a modern work environment. Assessment centers have many strengths: (a) They can measure complex attributes, (b) they are seen as fair and “face valid” by those who participate in them, (c) they show little adverse impact, (d) they predict a variety of criteria (e.g., performance, potential, training success, career advancement; Gaugler, Rosenthal, Thornton, & Bentson, 1987). Additionally, recent technological innovations have been incorporated into the assessment center method to allow the method to adapt to the globalization and computerization of the business environment (Lievens & Thornton, in press). Such advances include computer-based simulations, web-based assessment center delivery, software programs for scoring writing, voice tone, and other relevant attributes, and other aids for automating the assessment center process (Bobrow & Schlutz, 2002; Ford, 2001; Reynolds, 2003; Smith & Reynolds, 2002).

It is important to note that we are not advocating assessment centers as the “best” or “only” tool for carrying out human resource applications. In fact, there are disadvantages associated with using assessment centers that we discuss later in the chapter. We stress that the assessment center method, which was originally conceived in the 1940s (MacKinnon, 1977), has been evolving along with the world of work and offers just one “tried and true,” comprehensive method for assessing and developing a broad range of employee competencies.

A TYPICAL ASSESSMENT CENTER

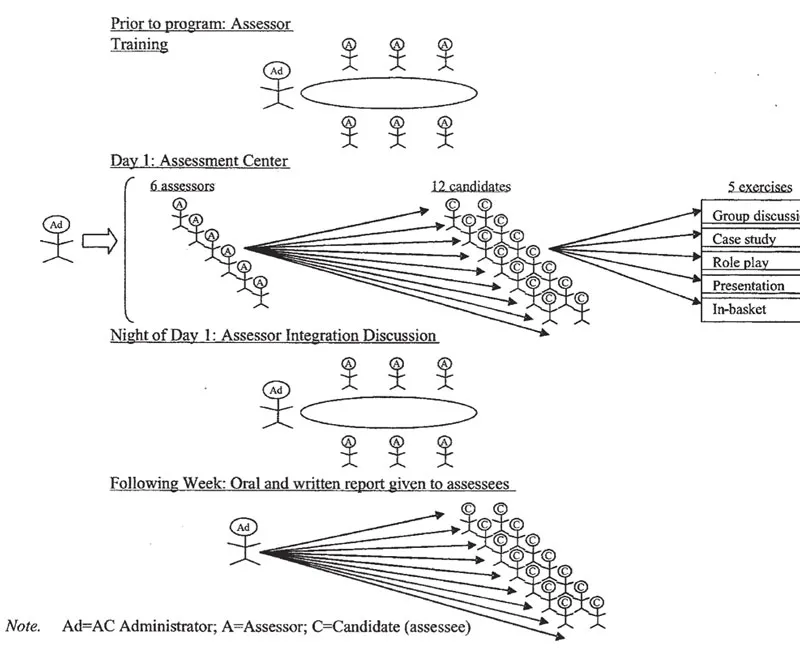

Here is how one assessment center works. We hasten to emphasize that there is really no typical or universal way that assessment centers are set up or conducted. On Monday morning, 12 participants or “assessees” (e.g., supervisors being considered for promotion to higher level management), 6 “assessors” (e.g., third level line managers, human resource staff), and an administrator report to a site away from the organization, such as a hotel. Prior to this time, the assessors have been trained to conduct the assessments, and the assessees have been briefed about the program. At the assessment center, the administrator provides orientation, makes introductions, and reviews the schedule. Over the course of the day, the participants take part in a series of simulation exercises and are observed by the assessors. While six participants are engaged in a group problem-solving discussion, the other six are individually analyzing a case study of an organizational problem and preparing a written report. Each participant then conducts a performance review session with a problem employee (a role player), makes a presentation of ideas for improving operations, and responds to material that has accumulated in the in-boxes (email, voicemail, desk in-basket) of a manager of a simulated organization.

Assessors rotate from exercise to exercise with laptops connected via a wireless network. In the exercises they observe and type notes. After each exercise they type a report summarizing the types of decision making, interpersonal, and communication behaviors demonstrated by each individual they were assigned to observe. These reports are electronically sent to the assessment center administrator who combines and prepares reports for the integration session at the end of the day. The rotation of assessors is such that that each participant is observed by at least three assessors.

At the end of the day, the assessees go home for the night, but the assessors spend the evening, and possibly the next day, discussing their observations and evaluating each assessee’s management potential. Each assessee is discussed at length. Assessors take turns reporting the behaviors they observed relevant to the performance dimensions. After all the reports are given, the assessors enter their ratings of the assessee on each performance dimension, using a 5-point scale. A spreadsheet is constructed to illustrate the ratings each assessee received from each assessor on each dimension. Using the spreadsheet, differences in ratings are discussed until assessors reach agreement. Next, individual ratings of the probability of success as a higher level manager (i.e., an overall assessment rating across dimensions) are entered for each assessee and discussed until consensus is reached. In many programs, the assessors then discuss the development needs of the assessee and make suggestions for what might be done to improve job effectiveness.

The following week, each assessee receives an oral and written report on how well he or she did. The detail and specificity of the feedback depends on the reason for using the assessment center. If the center is to be used for personnel decision making, reports may also be given to higher level managers who will be making such decisions. When the assessment center is used to diagnose development needs, feedback may be given to the assessee and his or her immediate supervisor to plan follow-up actions. These example events are depicted in Fig. 1.1.

It is important to note that this is just one example of assessment center operations. Chapter 2 describes how three other organizations designed their assessment centers. There are many variations on the basic theme. In particular, very different procedures are useful in integrating behavioral observations. In the example of Fig. 1.1, assessors discuss their ratings until consensus is reached. Another procedure gaining wider acceptance is the statistical integration of ratings. For example, some organizations compute an average of the individual assessors’ ratings to derive the final dimension ratings; others use a formula to combine final dimension ratings into an overall prediction of success. The advantages and disadvantages of various data integration methods are discussed in chapters 7 and 8.

COMPARISONS WITH OTHER ASSESSMENT PROCEDURES

The assessment center method is similar to some assessment procedures but quite different from others. For the purpose of making personnel decisions, there are techniques such as individual assessment in which an assessment practitioner assesses the job-relevant characteristics of individuals one at a time to make inferences about potential (Prien, Schippmann, & Prien, 2003). Typically, a trained psychologist uses psychological techniques to make a holistic judgment about a candidate’s fit with a job (Highhouse, 2002). For the purpose of developing employees, there are techniques such as multisource feedback which involves the collection of surveys from multiple raters (e.g., supervisors, co-workers, subordinates) about the effectiveness of an individual on a set of competencies. Typically, a feedback report is returned to the target individual (Bracken, Timmreck, & Church, 2001). Like assessment centers, these methods serve a variety of purposes, with individual assessment sometimes used for development (Prien et al., 2003) and multisource feedback sometimes used to make personnel decisions (Fleenor & Brutus, 2001). Alternative personnel assessment methods incorporate the use of personal history forms, ability tests, personality inventories, projective tests, interviews (Ryan & Sackett, 1998); work sample tests, integrity tests, biographical data measures (Schmidt & Hunter, 1998); interests, values, and preferences inventories (Heneman & Judge, 2003); weighted application blanks, as well as training and experience evaluations (Gatewood & Feild, 2001).

FIG. 1.1. A typical assessment center.

Each of these methods has strengths, and many have been found effective in predicting managerial success. Table 1.1 provides comparisons of some characteristics of assessment centers and other assessment techniques.

TABLE 1.1

Comparing Characteristics of Alternative Assessment Methods an...