![]()

Part One

General Survey of Early Types of Water Transport

![]()

1 Earliest times

Between 500,000 and 1,000,000 years ago, emergent Man made his way from the lightly wooded country of tropical Africa to the deserts of North Africa, the temperate woodlands of Europe and the forest tundra of Europe and Asia. There is little doubt about the starting-point of these travels since most authorities now agree that the first signs of human activity known to us, the manufacture of primitive stone tools, occurred in the African continent. This agreement extends also to the place for the evolution of Homo erectus. It was from Africa that this genus started to spread as an ancestral stock of modern man from Morocco to China and from South Africa to Germany.1 It is hard to believe that in this progress all the water barriers encountered were crossed by swimming alone.

The meagre and often difficult archaeological evidence for this expansion, fossil bones, stone tools, occasional wood or bone implements, or the even rarer living site, throws little light on this point, except in one case. If one looks at the distribution of these Early Stone Age remains, they are more concentrated in Africa, western and eastern Europe and southern and eastern Asia. There is thus a gap of a sort through central Europe to the Adriatic and Mediterranean.2 Furthermore, there are similarities between the north-west African finds and those in south-west Europe. All this may be due to the chances of archaeological survival, but it might also have some significance. Since the geological evidence3 shows that the Straits of Gibraltar have been in existence during the last two million or so years it looks as though there is at least a case for the first sea voyage having taken place in sight of the Pillars of Hercules.

There are problems, though, about this suggested drifting from Africa to Spain on a log or a piece of flotsam. One is the point at which the homonids learnt to swim. When our remote ancestors took to walking upright on two feet, they took an immensely important step towards the evolution of Homo sapiens by freeing the hands for tool-making and the consequent mental stimulation involved. At the same time they lost the faculty which four-footed animals have of being able to walk into water and then swim merely by continuing more or less the same action. The great apes in fact are prevented by their anatomical structure from using either an over-arm or a breast-stroke action and, not surprisingly, dislike and fear water. A good practical illustration of this is the shallow moat which sometimes confines these beasts on islands in zoos. The hominids must therefore have learnt to swim as a new achievement, and one would assume that no one would have attempted a crossing of the Straits of Gibraltar, even on some sort of float or raft, without this ability.

While, on the whole, Palaeolithic sites on the coast are rare, in England they seem frequently to cluster around rivers, such as the Thames and Medway in Kent or by lakes, like Hoxne in East Anglia. Remains of fish do not often occur on such sites,4 so there must be more interest in the evidence from some Lower Palaeolithic sites in Africa and Spain which suggests that hunted beasts were deliberately driven into swampy areas on the edges of rivers and lakes where they could be trapped in the mud and caught.5 For it cannot have been a long step in that situation to straddling a mass of floating reeds, or a floating log, and then turning eventually to the marine occupants of the lake, as well as the beasts floundering on its edges.

On the other hand, at least one study has emphasised the importance of the relative absence of fish from the Mousterian sites of Neanderthal man (70,000–30,000 BC), since the single specimens of fishes found at Salzgitter-Lebenstedt in northern Germany have to be set against the remains there of eighty reindeer and sixteen mammoths.6 What is suggested is that Virchow’s hundred-year-old diagnosis, that rickets accounted for the peculiar simian cast of some Neanderthal skeletons,7 can now be much more strongly maintained by modern anthropological and medical knowledge. According to Ivanhoe, the extreme variability of some Neanderthal skeletons can be related to two things, latitude and climate. North of latitude 40°, the lack of solar ultraviolet light, particularly in a cold period when caves or tents or furs would reduce the skin’s exposure to sunlight even further, necessitates an outside source of vitamin D. Two particularly rich sources are egg-yolks and fatty fish. While much of the evidence is negative, such as the absence of specialised fishing equipment or fish-remains at Mousterian sites, the general impression is certainly that Neanderthal man made very little use of fish. So it is not surprising that teeth and bone samples from Neanderthal fossil material have yielded unequivocal evidence of serious vitamin D deficiency and conditions practically specific of rickets.8 Moreover the further a sample is from the Equator and the more positively it can be dated to periods of unfavourable climate, the more it shows these symptoms. Deformation from rickets would go a long way to explaining some of the Neanderthal characteristics, so instead of having him as an odd sort of throwback, he would fit much more easily into a gradual transition from Homo erectus to Homo sapiens.

While this is a controversial theory, there is another of Ivanhoe’s conclusions that is widely accepted and relevant to possible early water travel. This is that the most important element of the more recent cultures (30,000 BC and later) was the development of fishing by means of an expressly developed tool assemblage which contributed substantially and routinely to the diet.9 The presence of fish-bones like the vertebrae necklace from Barma Grande, of fishing equipment like the fish-gorge from La Ferrassie in the Dordogne, and of representations of fish such as the one on the Montgaudier baton are confirmatory evidence.10

So this then may well imply that while roughly in the Mousterian period there was little attempt to catch fish and therefore go on the water either accidentally or deliberately, a sharp change occurred during the succeeding period of the Upper Palaeolithic. As well as fishing being reflected in the finds of fish-bones and fishing tools of this period, it would also imply a much greater temptation to go beyond wading depth among the now rickets-free Aurignacian people in their unconscious hunt for fatty-fish oil.

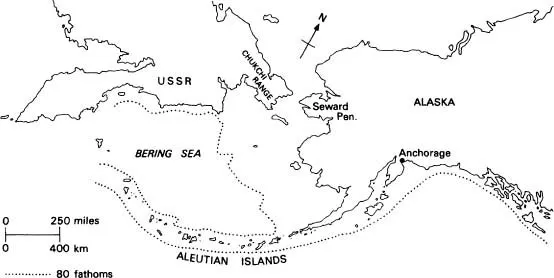

What Grahame Clark and Stuart Piggott call the first great climax of human achievement occurred in the later stages of the Late Pleistocene between 35,000 and 10,000 BC,11 when the Upper Palaeolithic peoples occupied the American continent and also Australia. Some writers have suggested that the first immigration from eastern Asia along the Pacific shores into America took place as much as 40,000 years ago, with another subsequently from central Siberia.12 Both might presumably have used the land-bridge between the Chukchi Peninsula in Siberia and the Seward Peninsula in Alaska (see Map 1.1). The continental shelf there is both wide and shallow, and if the locking-up of waters in the glaciers lowered the sea-level by as little as 150 feet relative to today’s level, it is calculated13 that a 200-mile-wide bridge would have emerged. Nor would glaciation have blocked the way. Both sides of the Bering Strait and the land-bridge itself appear to have been free of permanent ice. On the other hand, the to-and-fro movements of animals and plant species alike would appear to have needed a longer and warmer link than geological evidence can supply at the moment, and, as we shall see, it is at least possible to suppose that the earliest inhabitants of America had craft capable of short sea crossings or island-hopping.

Map 1.1 Siberia and Alaska and the Bering Strait

Man first came to Australia, too, by sea during this same period. After years of what D.J. Mulvaney once called ‘exotic claims by Australian optimists’, a series of radiocarbon dates from sites such as Lake Mungo and Kow Swamp have established not only that man reached Australia 40,000 years ago, but that one can also claim for Australia the earliest record of human cremation sites and some of the earliest occurrences of art.14 As Mulvaney says, going simply by the growing body of evidence from south-east Asia and Australia, it is now possible to suggest that man may have possessed water-craft considerably earlier in his technological history than hitherto believed.15

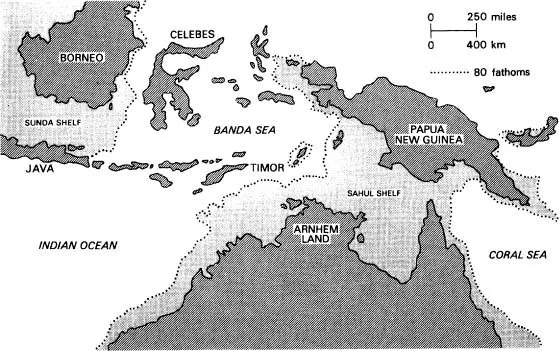

Even though the shallow Sahul Shelf joined New Guinea to Australia and the Sunda Shelf linked Borneo and Java during one of the Late Glacial stages (Map 1.2), migrating man, in contrast to the uncertain progress of the first Americans, would amost certainly have had to make a sea crossing of at least 180 kilometres on the Java-Timor island-hopping route and 95 kilometres on the Celebes–Moluccas one.16

In due course more detailed geochronological methods such as thorium-protoactinium dating,17 deep sea cores and a better understanding of the effect of the orbital precession of the earth’s long axis on the amount of radiation falling on the polar ice-caps may help to settle the problem of the rise and fall of sea-levels during the last 100,000 years. We will then know better whether the answer to such immigrations lies in land-bridges, which have perhaps on occasion been a little too easily called on to explain how they were achieved, or if in fact the evidence shows that early man must have travelled by water.

Map 1.2 The East Indies, Papua New Guinea and northern Australia, with the Sunda and Sahul Shelves (after Butzer, Environment and Archaeology, 1972)

Man undoubtedly used water-craft during the Palaeolithic period, but we cannot say exactly what types of craft these were. Nevertheless, by examining the distribution of the earliest known examples of water transport, and by looking at the range of craft recently in use in pre-industrial societies, and knowing Palaeolithic man’s technological capabilities, an informed estimate can be made of the craft probably used in the environment then prevailing. These matters are examined in the next three chapters. In the final chapter of Part I the dug-out canoe and its place in the evolution of the planked boat is considered.

![]()

2 Raft and reed

The single log

Traditionally man’s first craft is assumed to have been a floating log, the fortuitous gift of a swollen river – not that any evidence is ever likely to emerge to decide for or against this theory. Such a single unworked log has serious limitations, and real advance would not be possible until the development of some form of contrived craft. Although the use of fire was known, there is not much reason to suppose that these early hunters of the Lower Palaeolithic had either the tools or the margin of time available to stay in one place long enough for the fairly lengthy and elaborate operation of hollowing-out a dug-out. Similar considerations apply to the bark canoe. The abundance and wide distribution of flint scrapers suggest the skin clothing which must have made possible the northward advan...