![]()

Chapter 1

The Inventory of Soil Biological Diversity: Concepts and General Guidelines

M. J. Swift, David E. Bignell, Fátima M. S. Moreira and E. Jeroen Huising

SOIL ORGANISMS AND SOIL ECOSYSTEM SERVICES

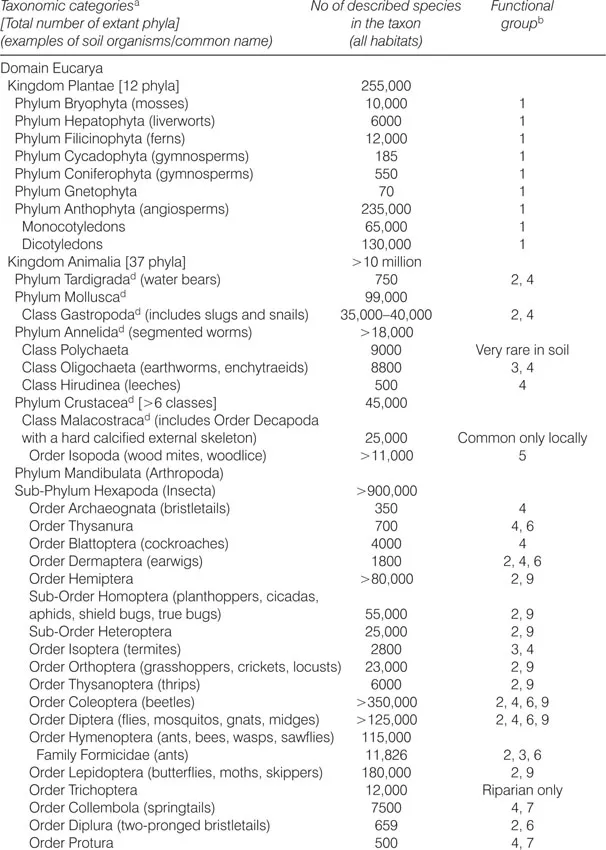

Soil is the habitat of an array of organisms in all three taxonomic domains (sensu Woese et al. 1990) and many phyla. The taxonomic classification of living organisms is still controversial (e.g. Margulis and Schwartz, 1998; Cavalier-Smith, 1998, 2004), especially regarding the taxa to be created at higher levels, and the numbers of such higher categories (such as kingdom) to be considered, in addition to domain. However, whatever classification system is used, the diversity of soil biota is high at all levels of analysis (for reviews, see Swift et al. 1979; Lavelle, 1996; Brussaard et al. 1997; Wall, 2004, Bardgett, 2005; Moreira et al. 2006). Table 1.1 lists the main phyla of eukaryotic organisms and prokaryotes that are or can be represented in the soil community, with more than 1.5 million species for the eukaryotes and an estimated species richness far beyond 10,000 for the prokaryotes.

Table 1.1 Number of described species in the main taxonomic categories of plants and of soil biota, and the main functional groups they represent

Source: After Moreira et al. 2006

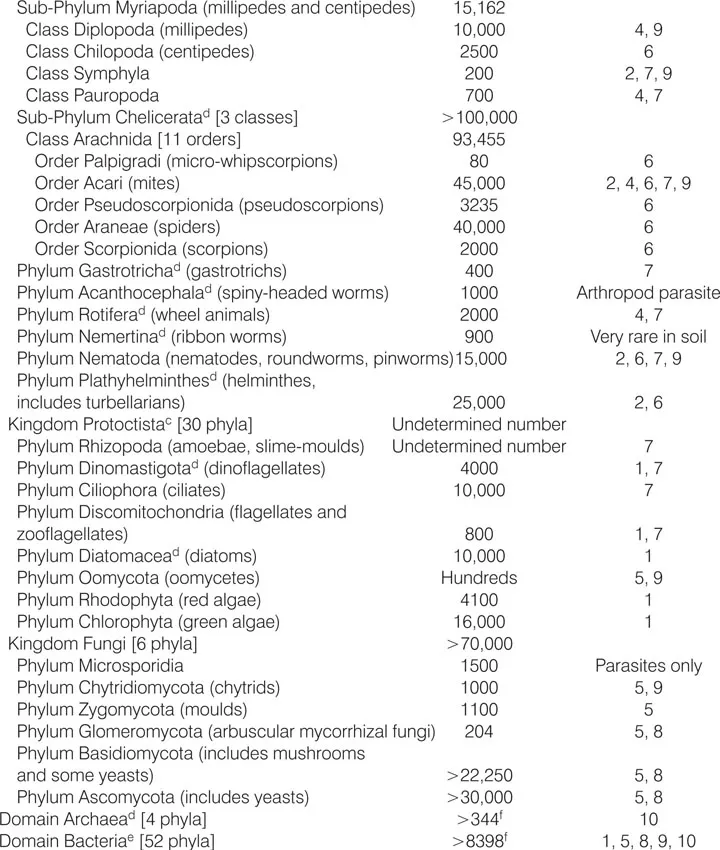

As it is neither practicable nor sensible to address all the organisms present when making an assessment of the biological health of soils (see Lawton et al. 1998), biota have been evaluated (relative to non-biotic agencies and between themselves) for their relative contribution to ecosystem processes (sensu Daily, 1997; Wall, 2004). These processes collectively support the provision of ecosystem services that contribute to the maintenance and productivity of ecosystems by their influence on soil quality and health (Hole, 1981; Lavelle, 1996, Brussaard et al. 1997; Kibblewhite et al. 2008). The processes can be grouped into four main aggregate ecosystem functions:

1 Decomposition of organic matter is largely brought about by the enzymatic activity of bacteria and fungi, but greatly facilitated by soil animals such as mites, millipedes, earthworms and termites, which shred the plant or animal residues and disperse microbial propagules. Together, the microorganisms and the animals involved in the process are called decomposers, but the term litter transformers has now come to be used to describe these animals, where they are not also ecosystem engineers (see below). As a result of decomposition, organic C is released into the atmosphere, predominantly as CO2 or CH4, but also incorporated into a number of pools within the soil as soil organic matter (SOM). These SOM fractions vary in their stability and longevity, but within a given soil type and environment a characteristic equilibrium exists between the SOM content and the inflows and outflows of C from the system.

2 Nutrient cycling, which is closely associated with organic decomposition. Here again the microorganisms mediate most of the transformations, but the rate at which the process operates is determined by small grazers (micropredators) such as protoctists, nematodes, collembolans and mites. Larger animals may enhance some processes by providing niches for microbial growth within their guts or excrement. Specific soil microorganisms also enhance the amount and efficiency of nutrient acquisition by the vegetation through the formation of symbiotic associations such as those of mycorrhiza and N2-fixing root nodules. Nutrient cycling by the soil biota is essential for all forms of agriculture and forestry. Some groups of soil bacteria are involved in autotrophic elemental transformations, that is, they do not depend on organic matter directly as a food source, but may nonetheless be affected indirectly by such factors as water content, soil stability, porosity and C content, which the other biota control.

3 Bioturbation. Plant roots, earthworms, termites, ants and some other soil macro-fauna are physically active in the soil forming channels, pores, aggregates and mounds, and moving particles from one horizon to another. These processes of ‘bioturbation’ influence and determine soil physical structure and the distribution of organic material. In so doing they also create or modify microhabitats for other, smaller, soil organisms and determine soil properties such as aeration, drainage, aggregate stability and water holding capacity. This set of organisms has therefore been called ‘soil ecosystem engineers’ (Stork and Eggleton, 1992; Jones et al. 1994; Lawton, 1996; Lavelle et al. 1997). Soil structure and properties are also influenced though the production by the animal engineers of faeces, comprising organo-mineral complexes that are stable over periods of months or more (Lavelle et al. 1997). Bioturbation plays a major role in the regulation of the water balance of the soil (infiltration, water storage capacity and drainage) and strongly influences its susceptibility to erosion.

4 Disease and pest control. The soil biota includes a wide range of viruses, bacteria, fungi and invertebrate animals capable of invading plants and animals (including humans) and causing disease and death. In natural ecosystems, intensive outbreaks of soil-borne diseases and pests are relatively rare, whereas such epidemics are common in agriculture. In healthy soils the activities of the potential pests and pathogens are regulated by interactions with other members of the soil biota, which include microbivores and micropredators that feed on microbial and animal pests respectively, as well as a wide variety of microbial antagonistic interactions. In agro-ecosystems this range of interactions may be reduced because of diminished biological diversity and/or soil environmental changes such as those caused by lowered SOM content.

Figure 1.1 shows the contribution made by the soil biota to ecosystem goods and services as a result of the above processes. In particular it should be noted that the interaction between organic matter decomposition, bioturbation and nutrient cycling will determine the balance between the equilibrium amount of carbon sequestered in the soil (see above) and the emissions of greenhouse gases (principally CO2, CH4, NOx, N2O). Soil organisms thus play an important role in the regulation of atmospheric composition and hence are major players in climate change.

Figure 1.1 The relationship between the activities of the soil biological community and a range of ecosystem goods and services that society might expect from agricultural soils

Source: From Kibblewhite et al. 2008

FUNCTIONAL GROUPS OF SOIL BIOTA

In principle, all the organisms listed as members of the soil community can be allocated to one or more of the four generic functional categories described above, based on the particular function they perform or the specific soil-based process they mediate. In order to link particular soil organisms (collectively soil biodiversity) to the generic functional categories and ultimately the ecosystem services (e.g. Setäla et al. 1998), we resort to the concept of key functional groups, usually defined on trophic criteria (Brussaard, 1998) but qualified by morphological, physiological, behavioural, biochemical or environmental responses, and to some extent by taxonomic character.

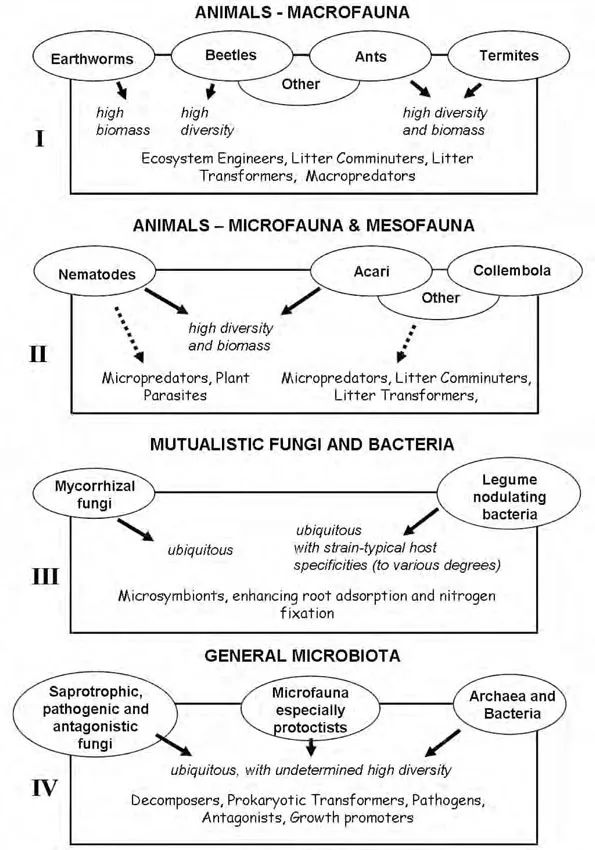

There is no precise agreement on the definition of the functional groups and how many of these groups should be discerned within in a typical soil environment, so the concept is heuristic and can be modified for whatever analytical purpose is in hand, but a good case can be made for at least ten categories. These are presented formally in Table 1.2 and used to annotate the taxonomic categories listed in Table 1.1. Note that some functional groups include a wide range of related and sometimes unrelated taxa, while others have high taxonomic specificity. For this reason, and because many components of soil biota are taxonomically intractable, there have been few studies of agricultural soil health in which the whole taxonomic spectrum has been sampled representatively in the same place and at the same time (Bignell et al. 2005).

Table 1.2 Key functional groups of soil biota

TARGET GROUPS OF SOIL BIOTA

In designing fieldwork the challenge is to select a subset of the soil biota that adequately reflects the anticipated taxonomic spectrum, and which at the same time includes all the functional groups considered important. The functional importance of any species or group of species is likely to be related to their relative abundance and biomass, so assessing presence/absence alone is insufficient to the above purposes. Nonetheless it is also important to also look within functional groups to discover those taxa that meet the criteria to be considered ecosystem engineers (sensu Jones et al. 1994), and keystone species (sensu Davic, 2003).

The taxonomic groups nominated below are thus selected on the basis of their diverse functional significances to soil fertility and soil quality (hence the term ‘target taxa’); and their relative ease of sampling, isolation and identification (Figure 1.2). These are the taxonomic groups that were addressed in the Conservation and Sustainable Management of Below-ground Biodiversity project (CSM-BGBD) and for which methods of inventory and characterization are provided in the subsequent chapters. Furthermore, a number of these taxonomic groups are very important in their own right as contributors to overall biotic diversity, for example beetles, ants, enchy-traeid worms, spiders, mites, nematodes and (probably) protoctists (protists), all of which comprise large numbers of species in comparison with other higher taxonomic groups (Table 1.1). In this context, the geographical distribution, the introduction of exotic and invasive species and loss of endemic species then also become a concern.

Figure 1.2 Main functional groups studied in the CSM-BGBD project classified according to domains and kingdoms, size and related ecosystem processes

The target groups included are:

1 Macrofauna – earthworms, which influence both soil porosity and nutrient relations through tunnelling, and ingestion of mineral and organic matter, and which act as regulators of soil biotic populations at smaller spatial scales, for example mesofauna, microfauna and microsymbionts.

2 Macrofauna – termites, ants and beetles, which influence or mediate a) soil porosity and texture through tunnelling, soil ingestion and transport, and gallery construction, b) nutrient cycles through transport, shredding and digestion of organic matter, and c) biological control as predators.

3 Other macrofauna such as woodlice (Isopoda), millipedes (Diplopoda) and some types of insect larvae, which act as litter transformers, with an important shredding action on dead plant tissue, and their predators (centipedes, larger arachnids, some other types of insect). Some species can also have detrimental effects by becoming pests.

4 Mesofauna, such as collembolans and mites, which act as litter transformers and micropredators (grazers of fungi and bacteria, and pr...