- 198 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

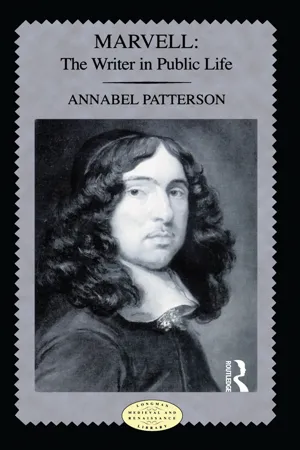

Marvell: The Writer in Public Life is substantially revised from Professor Patterson's well received 1978 study, including a new introduction and new chapter on Marvell and secret history. This important study provides an up to date perspective on a writer still thought of merely as the author of lyric and pastoral poems. It looks at both Marvell's political poetry and his often neglected political prose, revealing Marvell's life long commitment to writing about the values and standards of public life and follows his often dangerous writerly activities on behalf of freedom of conscience and constitutional government.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Marvell by Annabel M. Patterson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The portraits and the life

The two most important facts about Andrew Marvell, bio graphically speaking, are that (despite the misleading testimony of the Miscellaneous Poems) he never married, and that he spent almost two decades as a Member of Parliament for Hull, from 1659, when he was thirty-eight, until his death in the summer of 1678. Hull was his home town. His family had moved there in 1624 when Marvell was three. His father, Andrew Senior, was a moderate Puritan, appointed as lecturer in Hull’s Holy Trinity Church. Marvell probably attended Hull grammar school, and his return to public service for that town (though he mostly lived in London) tells us a good deal about his way of coping with the collapse of the English republican experiment in 1659–60.

So do his portraits. One of our surprises, as readers of Marvell’s taut and teasing lyric poems, is coming face to face for the first time with the heavy features painted, perhaps, by Sir Peter Lely, and now in the National Portrait Gallery (Figure 1): big nose, pouchy cheeks and chin, mouth too full for a man, especially in the lower lip, the whole not so much redeemed as rendered problematic by the fine wide eyes and challenging gaze that characterize so many of Lely’s portraits. George Vertue recorded in one of his notebooks that a portrait of Marvell by Lely was in the possession of the Ashley family;1 and in Upon Appleton House Marvell summons an image of Lely’s studio, with its ‘Clothes’ or canvases ‘strecht to stain’ (1. 444), implying that he had been there. On close inspection, this portrait, called the ‘Nettleton’, becomes enigmatic not only in its gaze but in its iconography. The plain white collar or ‘band’, the plain brown jacket and skull-cap share the ‘puritan’ semiotics of Lely’s commonwealth style, which would be fully expressed in his portraits of Oliver Cromwell or Peter Pett. But the exuberant hair implies more courtly tendencies, while peeking out from under the stiff band is some luxurious, softer, shinier stuff, whose identification as tasselled bandstrings does little to explain away the conflicting visual message. One would have liked to know whether Marvell had fine hands to match his eyes, but the oval frame (characteristic of Lely’s portraits of poets)2 excludes them from consideration.

FIGURE 1 Andrew Marvell, ‘Nettleton’ portrait, National Portrait Gallery, London

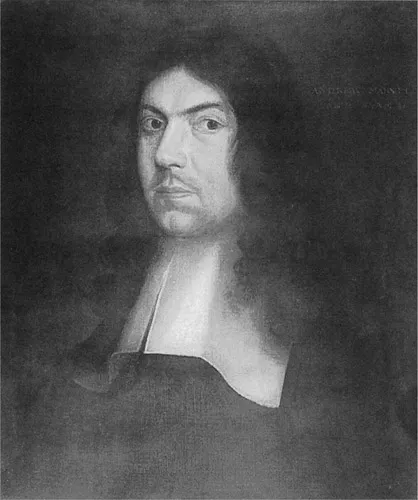

On either side of this portrait stand, we might say, representations of Innocence and Experience. Experience is featured in the ‘Hollis’

FIGURE 2 Andrew Marvell, ‘Hollis’ portrait, Hull Museums

portrait (Figure 2), so called because Thomas Hollis, the late eighteenth-century Whig philanthropist, acquired it in 1763, and gave us its first formal and ideological reading: Tf Marvell’s picture’, he wrote, ‘does not look so lively and witty as you might expect, it is from the chagrin and awe he had of the Restoration then just effected’. It ‘was painted when he was forty-one; that is, in the year 1661 … in all the sobriety and decency of the then departed Commonwealth’.3 Ideology here competes with aesthetic apology, an insight into Marvell’s feelings after the death of Oliver Cromwell and the collapse of the Protectorate; but for Thomas Hollis himself, who was the devoted collector behind the first edition of Marvell’s prose, this dour portrait was part of a record of integrity and commitment.

We may also, however, know what Marvell looked like as the picture of Innocence. In John L. Propert’s late nineteenth-century History of Miniature Art, there is a reference to ‘Samuel Cooper’s fine portrait of Andrew Marvell’,4 along with a reproduction of a miniature said to be of Marvell, but mysteriously there attributed to Mary Beale (Figure 3). Mary Beale was born in 1633, and married in 1652. This would make her younger than Marvell by twelve years, so she can scarcely have painted Marvell as a boy. Samuel Cooper, however, was born in 1608, and had established himself as a miniature painter by 1629, when Marvell was eight years old. It is not too difficult to see this graceful child still visible in the eyes and mouth of the ‘Nettleton’ portrait, and nothing in the image denies Propert’s identification. If this is a Cooper portrait of Marvell at, say, twelve years old, when he matriculated at Trinity College, Cambridge, its painting would be prophetic of both their careers. By 1650 Cooper’s chief patron was Oliver Cromwell, who sent Cooper’s images of him abroad to Dutch and French statesmen, as well as the portrait sent to Queen Christina of Sweden about which Marvell wrote a Latin poem. Cooper also painted Richard Cromwell, Thomas Fairfax, Secretary Thurlow, two of Cromwell’s generals, Richard Ireton and George Fleetwood, the lawyer Sir John Maynard, who managed the impeachments of Laud and Strafford, the regicide John Carew, the Leveller leader John Lilburne, and Thomas May, translator of Lucan, who scandalized many by changing loyalties and becoming the historian of the Long Parliament.

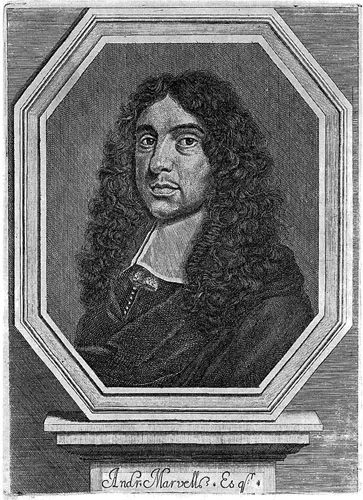

The last image of Marvell is in fact the ‘Nettleton’ portrait again, copied in reverse for the engraved portrait that appeared in his posthumously published Miscellaneous Poems of 1681 (Figure 4). Here the face is still heavier, the hair longer and more wig-like, the plain jerkin now swathed in a cloak, the eyes warier over deep bags, the mouth sensuous no longer. If we allow this series to represent the life, a narrative of Marvell’s gaze over the Revolution and the Restoration, the story, like the face, succumbs to the pull of gravity. Whatever self-contradictions were residual in the ‘Nettleton’ portrait (and we can perhaps imagine the ‘Nectaren, and curious Peach’ had once or twice reached themselves into those invisible hands), those who presented his image to a reading public in 1681 wished him to be admired for dourer, more reliable features.

Between his Hull childhood and dutiful middle age, whose record can be seen in the nearly 300 letters Marvell wrote to the Hull

FIGURE 3 Marvell as a boy, by Samuel Cooper (?), from John L. Propert’s History of Miniature Art (1887)

Corporation about parliamentary business, lay not quite a century of monumental events. Marvell’s response to these, or direct involvement in them, has to be pieced together from a set of fragmentary records and hints, some of which are his own poems. First came nine years

FIGURE 4 Andrew Marvell, frontispiece to Miscellaneous Poems (1681)

at Cambridge, interrupted both by his father’s accidental drowning in 1641, and by his own journeys through Holland, France, Italy and Spain between 1642 and 1647. Hilton Kelliher guessed that Marvell left England soon after the outbreak of the First Civil War and returned as soon as it ended.5 Early in 1651 he entered the employ of Sir Thomas Fairfax as tutor to his daughter Mary, and spent the next two years at Nunappleton House, the estate in Yorkshire to which Fairfax retired after resigning his command of the parliamentary armies. In February 1653 John Milton recommended him, unsuccessfully, to John Bradshaw, President of the revolutionary Council of State, as a candidate for the Latin secretariat. In July 1653, Marvell moved to Eton to become tutor to Cromwell’s prospective son-in-law, William Dutton, staying in the house of the puritan John Oxenbridge. The Dutton assignment seems to have continued through at least August 1656, when James Scudamore reported in a letter from Saumur in France the presence there of ‘Mr Dutton calld by the french Le Genre du Protecteur whose Governour is one Mervill a notable English Italo-Machavillian’.6

Since leaving his own place of higher education, then, the only signs of Marvell’s activities that have survived indicate that he had cosmopolitan manners (enough to be thought hyper-sophisticated or machiavellian) and saw himself primarily as an intellectual, one whose relation to high politics would be peripheral. In the early 1650s the connections he sought, or that were sought for him, placed him firmly apart from the king’s party, although, as at least his 1649 poem to Richard Lovelace demonstrates, he had friends among the cavaliers.7 Let us pause on that poem for a moment, not least because it has been read more than once as an expression of sympathy for the royalist cause. In fact, it merely expressed good will towards one particular royalist whose literary career has run into trouble because of his own political involvement, especially in forwarding to the Long Parliament the Kentish Petition against their proceedings; and Marvell develops that motif into a lament for the conditions of civil war culture in general.

To his Noble Friend Mr. Richard Lovelace, upon his Poems appeared as a commendatory poem in Lovelace’s Lucasta, which had had difficulty with the parliamentary censors. Even after licence had been granted in February 1647/48, publication was delayed until the summer of 1649, surely because of the ‘Sequestration’ or temporary confiscation of Lovelace’s estate to which Marvell’s poem refers. That punishment for ‘delinquency’, or taking up arms against the parliament, had been ordered by the Long Parliament on 28 November 1648.8 On 5 May 1649 Lovelace’s name appears in the Commons Journal in a list of delinquents whose cases were to be reconsidered with a view to mitigating their fines. Lucasta was registered for actual publication just over a week later. These events explain the otherwise peculiar directions taken by Marvell’s poem — certainly one of his earliest, but also one of his most sophisticated statements about the relations between writing and the world.

To his Noble Friend begins with the premise that ‘our times are much degenerate’ from those in which Lovelace conceived his poems: a chronology that conflates the Caroline era, so often described by court poets as a Golden Age, with the pseudo-medieval chivalry invoked by Lovelace, and both with the age of classical, Ciceronian rhetoric whose disinterested objective was social and political improvement; language in the service of the state. For this kind of ‘speaking well’, Marvell adopts the adjective ‘ingenious’, derived from the classical ingenium, an interesting conflation of high intelligence with cleverness or wit, from which derive both our ‘genius’ and ‘ingenuity’. Marvell would return to this term as a problematic ideal in one of his late polemical pamphlets; but here he is concerned with the collapse of the classical ideals:

Modest ambition studi’d only then,

To honour not her selfe, but worthy men.

These vertues now are banisht out of Towne,

Our Civill Wars have lost the Civicke crowne.

He highest builds, who with most Art destroys,

And against others Fame his own employs.9

To honour not her selfe, but worthy men.

These vertues now are banisht out of Towne,

Our Civill Wars have lost the Civicke crowne.

He highest builds, who with most Art destroys,

And against others Fame his own employs.9

Since then, Marvell complains, ‘our wits have drawne th’infection of our times’; ‘Civill’ and ‘Civicke’, though obviously related etymologically, have become antagonists; and he equates the negativity of the ‘grim consistory’ (the Long Parliament) and the ‘yong Presbytery’ (the Westminster Assembly) with the generally negative criticism supplied by the ‘barbed Censurers’, (ordinary readers who have translated the real hostilities of the times into trivial logomachias). A complicated series of puns connects the verdicts of these ‘Word-peckers’ with Lovelace’s political difficulties:

Some reading your Lucasta, will alledge

You wrong’d in her the Houses Priviledge.

Some that you under sequestration are,

Because you write when going to the Warre.

You wrong’d in her the Houses Priviledge.

Some that you under sequestration are,

Because you write when going to the Warre.

In the first of these couplets Marvell alludes to the privilege of freedom of speech within the Commons, a privilege limited, however, to Members of Parliament, and denied to the rest of society specifically by the 1643 Printing Ordinance, against which Milton had delivered his famous ‘speech’, Areopagitica. In the second, he plays with the title of Lovelace’s most famous poem, To Lucasta, ongoing to the war, making it serve the charge that Lovelace has confused literature and politics, as his parliamentary censors have also, of course, more ostentatiously done. This was not, however, a distinction that Marvell himself would be able to observe much longer.

There are two ways of regarding the next eight years of Marvell’s career, from 1650 to Cromwell’s death in 1658. By September 1657 Marvell had at last acquired a junior position in the Latin secretariat, under John Thurloe and with Milton. During this period he wrote three poems to or about Cromwell which we can date with some precision: the Horatian Ode on Cromwell’s return from Ireland in May 1650; the First Anniversary of the Government under O.C., which was advertised for sale in Mercurius Politicus in January 1655, but with no author’s name attached; and the elegy for Cromwell’s death, which occurred on 3 September 1658. He also wrote, presumably for Fairfax, three complimentary ‘estate’ poems, Epigramma in Duos monies, Upon the Hill and Grove at Bill-borow, and Upon Appleton House, all (again presumably) before he left Fairfax’s employment. On the basis of this evidence it has become customary to read Milton’s letter to Bradshaw as a significant dividing line, indicating for the first time Marvell’s wish for some kind of political post; three years of ‘detached’ leisure and creative privacy are thus separated from five years of increasing commitment to Cromwell and decreasing literary significance. Not only the ‘pastoral’ poems but the Horatian Ode are thus assigned to the Fairfax period, as a time when Marvell was gracefully free of partisanship. Alternatively, the Ode is itself seen as the dividing line, written at the century’s midpoint, when Marvell was still capable of examining dispassionately the claims of both Charles I (so recently executed) and Oliver Cromwell (so clearly the most powerful man in the state) to legitimacy and admiration.

The other way of considering Marvell’s Protectorate poetry, and one I shall argue at length in the next chapter, is to see it as a whole, as a series of interdependent studi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Author’s acknowledgements

- Publisher’s acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 The portraits and the life

- Chapter 2 Experiments in praise

- Chapter 3 Devotional poetry

- Chapter 4 Experiments in satire

- Chapter 5 The pamphlet wars

- Chapter 6 The naked truth of history

- Appendix The second and third advices to a painter

- Bibliography

- Index