![]()

THE ANCIENT MAYA AND THEIR CENTRAL AMERICAN NEIGHBORS

Geoffrey E. Braswell

Central America is often left out of books on the Maya. Focusing on the Maya in isolation, without including their neighbors, is a mistake. Indeed, our knowledge is enormously enriched when we see the Maya – along with their allies, enemies, and trading partners – as embedded in a world that includes their neighbors to the south. These neighbors include Nahua peoples of Chiapas, southern Guatemala, and El Salvador, Lenkan speakers of Honduras and El Salvador, Xinka of southern Guatemala, and pockets of Oto-Manguean speakers in most of these places.

The ancient Maya are famous for their large stone pyramids, hieroglyphic writing system, complicated calendar, and beautiful stone sculpture. Yet none of these accomplishments were unique to their civilization. Instead, these cultural achievements were shared across southern Mexico and northwestern Central America, an area that scholars call Mesoamerica. Nonetheless, Maya civilization is often studied either within a vacuum, by subregion, or according to modern political borders. As a result, many textbooks and edited volumes consider the southern lowlands of Guatemala and Belize but omit the Maya highlands and northern lowlands of Yucatan. When archaeologists do seek a broader context for the ancient Maya, they usually look to the northwest and consider only the most powerful urban civilizations of central Mexico – the Olmecs, Teotihuacanos, Toltecs, and Aztecs. Seldom are the Maya and their southeastern Central American neighbors of El Salvador and Honduras considered together, despite the fact that they engaged in mutually beneficial trade, intermarried, and occasionally made war and conquered each other. Central America is often left out of books on the Maya. Focusing on the Maya in isolation, without including their neighbors, is a mistake. Indeed, our knowledge is enormously enriched when we see the Maya – along with their allies, enemies, and trading partners – embedded in a world that includes their neighbors to the south.

One purpose of The Maya and Their Central American Neighbors is to begin to rectify this by presenting original research spanning the whole of the Maya area, including the too often overlooked northern lowlands of Mexico (Bey 2006: 16). We also consider the linguistically mixed regions of southern Guatemala and western Honduras – where the Maya lived alongside people who spoke other languages – and non-Maya eastern El Salvador. In order to achieve more balance, each of the major regions considered in our book is given two or three chapters. Because of the enormous expansion of research in recent decades, it is no longer possible to treat within a single volume all the advances in our understanding of the ancient Maya, let alone those of the many complex and more simply organized peoples who lived to their south and southeast. Our treatment here must be limited and is admittedly biased towards our own research interests. We credit these to one man and the intellectual legacy he has given us.

This volume is the second resulting from sessions held in honor of E. Wyllys Andrews V at the seventy-fifth annual meeting of the Society for American Archaeology (SAA) in Saint Louis in 2010. The first volume (Braswell 2012a) and session focused on important recent developments in our understanding of the prehistory of the northern lowlands, that corner of the Maya world where the Andrews family has made a singularly strong mark. The second session, organized by Winifred Creamer, considered Will Andrews’s important and continuing contributions to our understanding of the prehistory of Central America, especially through projects he directed in El Salvador and Honduras. Andrews’s impact as a scholar and mentor has also influenced research in Guatemala and Belize, particularly in regards to our understanding of ancient pottery. This volume includes some chapters derived from our Central American session and several others that round out our coverage of Mesoamerica, from Yucatan to El Salvador.

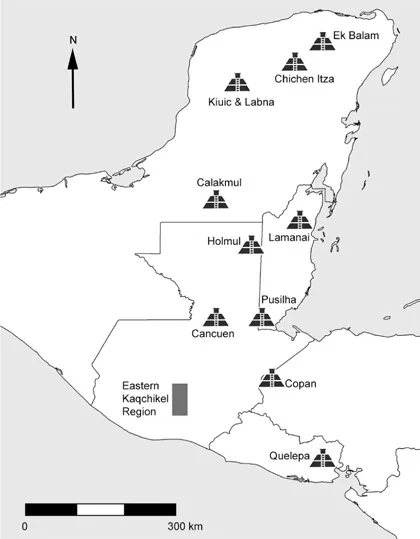

The current work considers a wide variety of topics, methodologies, and cultures of Mesoamerica. For this reason, I have not endeavored to write a synthetic introduction of the sort that began The Ancient Maya of Mexico: Reinterpreting the Past of the Northern Maya Lowlands (Braswell 2012b). Nonetheless, several themes run throughout this book, ones that parallel Andrews’s own interests and – in some cases – that are derived directly from his work. First, the volume is organized according to different regions of southeastern Mesoamerica. If we include early work, Andrews has conducted archaeological field research in most of these regions (Figure 1.1): Quelepa (El Salvador), Copan (Honduras), Seibal (Guatemala), and Komchen (Yucatan, Mexico). Second, many of the individual chapters focus on the origins of complex society in southeastern Mesoamerica or on its disintegration. By this, I refer to the earliest Preclassic (Formative) pottery and permanent settlement, and also to the famous “Maya Collapse” of the Terminal Classic period. Third, Andrews’s and our own studies of ceramics and architecture have concentrated on interregional cultural interaction, the spread of ideas and symbolic systems, and identity. A fourth thread in both this volume and Andrews’s research is the royal court, specifically the excavation of palaces in order to understand chronology, collapse, and broader issues related to political structure, economic organization, and power. Associated with this is the perception of how royal courts are understood through dynastic history. A fifth theme that runs through this work is the patterning of ancient settlement. Andrews’s own impact on settlement studies was most strongly seen in his mapping and demographic research with William Ringle in northwest Yucatan (Ringle and Andrews 1990). Two contributions to our volume build directly on Andrews’s dissertation research at Quelepa, El Salvador, by analyzing architecture and settlement patterns at that site. The final and clearest strand running through and unifying our work is Will Andrews himself. Most of the contributors to this volume are his students, and all of us have benefited greatly from his thoughts, research, and guidance.

FIGURE 1.1 The Maya and their Central American neighbors: sites marked with pyramid symbols are the subjects of chapters in this volume; the mapped portion of the Eastern Kaqchikel highlands is shown in dark gray. Additional relevant sites are shown in Figures 8.3, 10.1, 12.2, 13.1, and 14.1.

The book is structured by area, beginning with non-Maya El Salvador and multi-ethnic Honduras. These are discussed in three chapters. The second section is dedicated to highland Guatemala and its relations to non-Maya peoples living in the Pacific piedmont and on the south coast. The Maya highlands form an area that too often is ignored outside of the world of Guatemalan archaeology. The third section comprises three chapters that focus on the southern and central lowlands of Guatemala and Mexico, while the two chapters of Part IV consider the eastern periphery of Belize. The next two chapters discuss the northern lowlands, an area that, despite its importance, is not often given equal weight in discussions of the Maya outside of Mexico. The final contribution examines the Norte Chico of Peru, an area far removed from Mesoamerica, but presents an important theoretical analogy that has been used to understand Maya state formation.

Rather than follow the areal order of the sections of this book, in this introduction I emphasize the theoretical and substantive aspects of our work that tie it together into a single volume.

Preclassic origins

The origins of Preclassic village life, the adoption of agricultural economies, and the first use of pottery in southeastern Mesoamerica are pivotal topics of Maya archaeology. But it is fair to say that they have not been subject to sustained research at the level they deserve. Andrews has made particularly important contributions to these subjects through his definition of the Uapala sphere in the southeastern periphery of Mesoamerica (Chapter 2; Andrews 1976), his description of Middle Preclassic architecture and ceramics in northwest Yucatan (Andrews 1988, 1990), his reappraisal of the Swasey complex (Andrews and Hammond 1990), his general discussion of early ceramic spheres in the Maya lowlands (Chapter 7; Andrews 1990), and, most recently, his identification of very early pottery in the northern Maya lowlands (Andrews and Bey 2011; Andrews et al. 2008).

Experiments with horticultural life ways began in many regions of southeastern Mesoamerica during the late Archaic (or Preceramic) period (Chapter 5; Neff et al. 2006; Pohl et al. 1996). Nonetheless, evidence for permanent villages dating to before about 1100 BC (calibrated) is limited largely to the Pacific Coast and piedmont region of southern Chiapas and Guatemala, highland Honduras, the Salama Valley of Alta Verapaz (Sharer and Sedat 1987: 428), and perhaps Kaminaljuyu (Popenoe de Hatch 1997, 2002). Moreover, most sites where there is strong evidence for pottery dating to this early time are in regions where a close linguistic affiliation with Mayan languages seems unlikely. Put another way, we still lack unambiguous evidence that the lowland Maya lived in Early Preclassic villages and made pottery much before about 1100 BC (Lohse 2010: 343). Despite this, research at sites including Cahal Pech, Blackman Eddy, Cuello, Colha, Seibal, Altar de Sacrificios, Tikal, Komchen, and Kiuic demonstrate that settled villages where pottery was produced certainly existed during the period 1000 to 800 BC and perhaps a century earlier. There is still debate as to whether all of these early sites were inhabited by “Maya” (e.g., Ball and Taschek 2003) and whether or not the phrase “Early Preclassic” should be used to describe the time period when such pottery was first produced (see Chapter 7, note 1). Incised symbols on the earliest known pottery of the Maya lowlands are related to a complex that first appeared several centuries earlier and farther west during the Early Preclassic period. Nevertheless, their first manifestation in the Maya lowlands occurred at a time very close to the arbitrary beginning of the Middle Preclassic, at 900 bc (uncalibrated). If the Terminal Archaic and Middle Preclassic of the Maya lowlands were separated by an Early Preclassic period, current evidence suggests it did not last much more than a hundred years (Cheetham 2005: fig. 3.2; Garber and Awe 2009; cf. Lohse 2010). Thus, after nearly 2,000 years of experimentation with horticulture, the first permanent villages with pottery-using occupants developed quite rapidly in the Maya lowlands. There is no long Early Formative sequence for the Maya lowlands comparable to those of the Valley of Oaxaca, southern Veracruz, the Basin of Mexico, or the Pacific coast of Guatemala and Chiapas.

In Chapter 7, Niña Neivens de Estrada discusses an early ceramic complex from the site of Holmul, Guatemala. In a very real sense, Holmul is where archaeological studies of Maya pottery began (Merwin and Vaillant 1932), so it is fitting that some of the earliest pottery in the Maya lowlands should be found there. Pottery belonging to the K’awil complex (1000–850 BC) was recovered from architectural fill contexts at Holmul and cross-dated by comparison with similar “Pre-Mamom” pottery (i.e., lowland ceramics dating to a time before the second half of the Middle Preclassic) from sites in Belize and Guatemala. An important aspect of Neivens de Estrada’s study is that, following Andrews’s (1990) example, she viewed collections of early pottery from all the important southern lowland sites with Pre-Mamom ceramics. The K’awil complex shows close ties with the Cunil/Kanocha (defined first at Cahal Pech and Blackman Eddy), Eb (Tikal), and Xe/Real Xe (Altar de Sacrificios and Seibal) complexes from Peten and western Belize. In fact, it contains the full range of forms, slip colors, and incised designs represented at these early sites as well as types that were previously unreported. Among these is Jobal Red, with a distinctive red micaceous slip that sometimes contains specular hematite. The closest similarities to Jobal Red are found not in the Maya lowlands but in the Pacific coast and highlands of Guatemala, in accord with some speculations about the origins of Mayan languages. Incised white wares at Holmul also point to contacts with these areas.

Neivens de Estrada clearly disagrees with scholars who argue that the presence of pan-Mesoamerican (or “Olmec,” if one is so inclined) incised motifs implies an influx of non-Maya people at the time that settled village life appeared in the Maya lowlands. In fact, she points to a growing body of evidence from Holmul and elsewhere that continuous occupation began in the eastern lowlands at least 300 years earlier, during the Terminal Archaic period. Instead of positing migration, she suggests that the earliest potters and pottery consumers at Holmul participated in a very large network over which ideas about ceramics and symbols were shared. Interaction was closest and most frequent among Holmul and its near neighbors in the central Peten and western Belize, but inter-community ties also indirectly linked Holmul to more distant sites in northern Belize, southwestern Peten, the southern Maya region, and even highland Mexico.

Chapter 5, by Eugenia Robinson and me, considers the origins of complexity in the Maya highlands of Guatemala, specifically within the departments of Sacatepequez and Chimaltenango. In the eastern half of the Kaqchikel region, we surveyed some 350 square kilometers of terrain, stretching from the southwestern slopes of Alotenango Volcano almost to the Motagua River (see Figures 1.1 and 5.1). Moreover, we conducted excavations at several sites. Tantalizing evidence of landscape modification and the introduction of cultigens can be found dating back well into the Archaic period, but – as elsewhere in Guatemala (Neff et al. 2006) – we still lack clear evidence of living floors, hearths, and other features dating to this early occupation. Although a gradual in situ development from Terminal Archaic seasonal foraging and horticulture to settled village life seems likely, sites with unambiguous evidence of this pattern are still lacking. In part, this is because of the extremely dynamic and ever changing landscape of the southern Maya highlands, where volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, and all too frequent landslides bury, disturb, or obliterate many sites. But this is also a reflection of how little archaeological research has been targeted at searching for pre-ceramic occupations.

As in the Maya lowlands, there is little evidence of a long Early Preclassic tradition. In the Kaqchikel highlands, a few sherds with Pacific and piedmont affinities suggest ties to that region. The Arevalo complex at Kaminaljuyu (Popenoe de Hatch 1997, 2002) might date to the ve...