- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Gothic Europe 1200-1450

About this book

This uniquely ambitious history offers an account of all aspects of cultural activity and production throughout the world of Latin Christendom 1200-1450. Beginning with a detailed description of the political and economic circumstances that allowed the 'Gothic Moment' to flourish, the body of the book is both a celebration of the Gothic cultural achievement - in cathedral-building, in manuscript illumination, in chivalric love-romance, in stained glass and in many other arts - and an investigation of its social origins and systems of production.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Gothic Europe 1200-1450 by Derek Pearsall in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

‘Gothic Europe’: The Political and Economic Order

Why ‘Gothic’?

‘Gothic’ in ‘Gothic Europe’ signifies a period when the style of architecture that later came to be known as ‘Gothic’ was dominant. It was a style of architecture so innovative and extraordinary, so powerfully visible still, especially as it is manifested in the great cathedrals of western Europe, that it is not surprising that it has given its name to a whole period. This is not to say that it is easy to define: as Ruskin said, in ‘The Nature of Gothic’, defining ‘Gothicness’ is like trying to define the nature of red when there is only purple and orange to work with.1 The extension of the term to sculpture and painting and the decorative arts was natural enough, given that the display of those arts was mostly in architectural contexts (the carved figures in and on church buildings, the paintings in glass, on the walls and on altarpieces) or incorporated architectural motifs (the canopies and pinnacles of ‘Gothic’ illumination).

Some scholars have attempted to find the character of Gothic architecture, subjectively defined in terms of delicacy, fineness of detail, restlessness, mobility, in the non-visual arts such as literature. In a passage made famous for English medieval literary scholars by the quotation from it in Charles Muscatine’s book on Chaucer and the French Tradition, Arnold Hauser offers a version of what has become a common generalisation about Gothic art:

The basic form of Gothic art is juxtaposition. Whether the individual work is made up of several comparatively independent parts or is not analyzable into such parts, whether it is a pictorial or a plastic, an epic or a dramatic representation, it is always the principle of expansion and not of concentration, of co-ordination and not of subordination, of the open sequence and not of the closed geometric form, by which it is dominated. The beholder is, as it were, led through the stages and stations of a journey, and the picture of reality which it reveals is like a panoramic survey, not a one-sided, unified representation, dominated by a single point of view.2

Muscatine has no difficulty in finding these elements of ‘co-ordinateness and linearity’ in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, as well as ‘a second typically Gothic quality, the tension between phenomenal and ideal, mundane and divine, that informs the art and thought of the period’. These ideas of ‘Gothic form’ are widely current, and offer many temptations to make analogies between the arts, and particularly to argue from the aesthetic of visual form in architecture and art to the aesthetic of verbal and non-visual form in literature. Anyone writing about the different arts and their interaction and mutual influence within a certain period will want to make use of these and similar analogies. But the dangers of merely subjective impressionism are obvious, and one has to remain aware of the slippery nature of such analogies and the illusory foundation on which they are constructed. However, for the use of ‘Gothic’ as a periodising term, and as a means therefore of labelling all the forms of art produced within the period so designated, there is every justification.

‘Gothic’ was first introduced by Giorgio Vasari (1513–74) in his Lives of the Italian Painters as a term to describe the kind of old-style architecture that he despised.3 Admiring the architecture of Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446) and the painting of Raphael (1483–1520), and considering the recent painting, sculpture and architecture of northern Italy as a ‘renaissance’ of classical art, the only kind of art to be admired, he dismissed the architecture of the previous centuries as barbaric (maniera Barbara). It was, said Vasari, in the famous philippic against the Gothic style in the Introduction to the Lives, in the ‘German’ (todeschi) style or ‘the Gothic manner’ (maniera de’ Gotti). Vasari had a theory that the architecture he despised was actually invented by the historical Goths (who surged across Europe in the fifth century and, under Alaric, sacked Rome in 410). A report on Roman antiquities presented by a member of Raphael’s circle to Pope Julius II says that the pointed arches and overarching ribbed vaults were imitations of the northern forests where the barbarians constructed rude shelters by leaning trees together. Earlier Gothic (what is now called Romanesque) was meanwhile presumed to imitate the caves and grottoes in which these primitive people had lived even before they hit upon the idea of bowers under spreading leafy branches.

Abuse was heaped upon this Gothic architecture in the sixteenth and seven-teenth centuries. Sir Henry Wotton, in The Elements of Architecture (1624), comments upon pointed arches thus:

These, both for the natural imbecility of the sharp angle itself, and likewise for their very uncomeliness, ought to be exiled from judicious eyes, and left to their first inventors, the Goths and Lombards, among other reliques of that barbarous age.

At the same time, buildings continued to be restored and extended, skilfully and lovingly, in the Gothic style. San Petronio in Bologna had its nave rib-vaulted in 1646–58, Saint-Germain-des-Pres in Paris in 1644–45, and Saint-Etienne in Caen and Saint-Nicholas in Blois at around the same time. Lincoln College, Oxford, had its ‘fourteenth-century’ Gothic chapel built in 1631, and the Gothic fan-vault above the stairs leading to the hall of Christ Church, Oxford, dates from 1640. Engravings in books of architectural history such as Dugdale’s History of St Paul’s Cathedral (1658) reflect the love of Gothic. All of this is before Gothic was restored to official favour in the late eighteenth century as the perfect expression of a ‘natural’ aspiration after the divine. This was the analogy favoured in Goethe’s eulogy of Strassburg Cathedral (1772): ‘It rises like a most sublime wide-arching Tree of God, which with a thousand twigs, a million twigs, tells forth to the neighbourhood the glory of God’. It was not long before Gothic was canonised as the supreme architectural style, anatomised and classified (the supreme accolade) into its different periods (‘Early English’, ‘Decorated’, ‘Perpendicular’, for instance, in Thomas Rickman’s Attempt to discriminate the Styles of Architecture in England from the Conquest to the Reformation, 1817), and adopted on a massive scale for new building, ecclesiastical and secular.

Meanwhile, of course, Gothic had also taken its ‘Gothick’ turn, first in a patronising and playful manner in ‘Gothick’ novels like Horace Walpole’s Castle of Otranto (1764), full of vaults, crypts, tombs, painted windows, gloom and dark pomp, and then in a more seriously ridiculous manner in the novels of ‘Monk’ Lewis and Ann Radcliffe. Samuel Johnson, as a representative of neo-classical rationality, had celebrated the robustness of the ordinary, of truth to nature and the centrally human. The Gothic novel was in some sense a reaction against this, a return of the repressed, a tantalising visitation of the grotesque horrors that lay in the shadow of the Enlightenment. The pervasively religious presences of the Gothic novels – the ubiquitous monks and ruined chapels and suggestions of mysterious supernatural powers – provide one of the links with the past of Gothic, and indicate the nature of some of the spectres that haunted an age of reason (and that remained unappeased in the later literature of vampirism and postmodern schlock-horror).

The familiarity of the Gothic style in architecture, and the visual impact of its many surviving monuments, make it an appealing term to use to identify, if not to characterise, the period in which it was dominant. The exact definition of the chronological extent of that period could vary. If it were being defined in terms of architecture alone, ‘Gothic Europe’ would begin in 1144, with Abbot Suger, and end in the sixteenth century, sprawlingly, as neo-classical architecture spread from Italy northwards. It would begin early in one part of Europe and end late in other parts (Portugal, England). But though the history of architecture provides the initial justification for the use of the term Gothic, there is no reason to give it too solitary a prominence in arbitrating upon chronological divides. ‘Gothic Europe’ may be acknowledged to be a convenient periodising term, and 1200–1450 inevitably to some extent an arbitrary slice out of the flux of time, but there are a number of ways in which ‘Gothic Europe 1200–1450’ can be claimed to have, for ‘non-Gothic’ reasons, a definable identity and integrity.

Why 1200–1450?

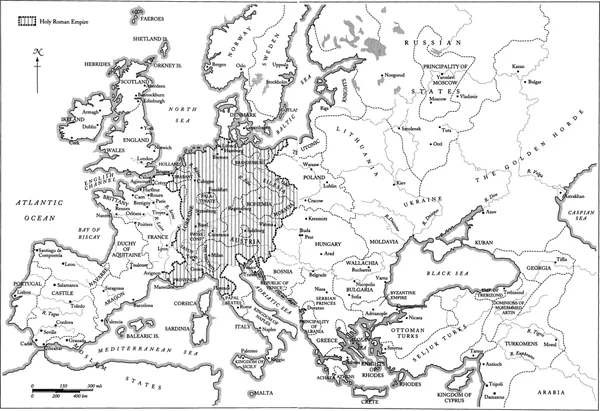

We begin with what defined the Europe we are speaking of. It was the Europe of Latin Christendom, extending north-west to newly Christianised Iceland, south-west to the disputed borders with the Moors in Spain, north-east and east to the Slavic kingdoms beyond Poland and Hungary, under the Eastern not the Roman Church, and south-east to the borders of the Eastern or Byzantine Empire. The Eastern or Greek Orthodox church had its headquarters in the imperial capital of Constantinople and claimed, like the Western or Roman church, from which it had finally split in 1053, to be the only true church. Since differences between different Christian sects are often as fiercely maintained as differences between Christians and non-Christians, the Byzantine Empire and the church of which the Patriarch in Constantinople was the head were almost as alien to the west as the Muslim Turks. The earlier crusades to recover the Holy Land inspired some fitful cooperation, but the sack of Constantinople by the crusading armies in 1204 during the Fourth Crusade confirmed the hateful division, defining western Europe as an identity through the oppositional structuring of what it was not, whether Turk or apostate. A further barrier between east and west was erected in the north, where the Mongol invasions of Russia acted to seal off a region that had previously been open to economic and cultural contact with the west. Relationships between the west and Byzantium improved spasmodically during the next two-and-a-half centuries, but it was again events in the east, the seizure of Constantinople by the Ottoman Turks in 1453, and the flight of scholars and the spread of Byzantine Greek learning to the west, that led to a new definition of western Europe. It was not only what happened within western Europe during the years 1200–1450 that makes it capable of being talked about as ‘Gothic Europe’, but also what happened in the east to make the west ‘the west’.

Map 1 Europe, about 1360.

The Byzantine Empire and the Turks

The Byzantine Empire had declined from the peak of its power (c.1025), when it controlled all Asia Minor and nearly all the Balkans. The Turks were pressing upon its borders, and though they were temporarily discomfited during the First Crusade, which culminated in the capture of Jerusalem in 1098 and the slaughter of all its Muslim and Jewish inhabitants and the setting up of the Latin kingdom of Jerusalem, they soon regrouped and united under Saladin to reconquer Jerusalem in 1187. Meanwhile, adventures in ‘Outremer’, as it was called (‘the overseas’), had given a tremendous stimulus to trade, chiefly conducted by Venice, but also Genoa and Pisa. The carnage of 1204, when the armies of the Fourth Crusade turned aside to sack Constantinople, was prompted by Venetian trading rivalry as well as religious fervour and the prospect of holy looting among the renegade Christians. A Latin empire was set up, the Western church installed, and much land in the Balkans and across the Bosphorus annexed. The Byzantines held on in western Greece and re-occupied Constantinople in 1261, but their shadowy empire remained a prey to exploitation by the fleets of Venice and Genoa, as well as by the Turks, and portions of it were occupied and garrisoned by the west to protect trade and crusading routes. The island of Rhodes was occupied by the Knights of St John (the Knights Hospitallers), a crusading order set up for this purpose (another was the Knights Templars, suppressed by the French king in 1312), right up until the end of the Middle Ages (1522).

Crusades continued spasmodically, though not many reached the Holy Land. The Emperor Frederick II had some temporary success in 1228–29, negotiating with the Muslims to have himself crowned in Jerusalem in 1229 (no one was there to crown him in any official capacity, so he crowned himself), but the city was reoccupied in 1244. This led Louis IX of France, shamed by the compromises and greed of his predecessors, to launch a new crusade in 1248. Well-organised and well-financed, the crusading army landed in Egypt, but got no further. Louis IX tried again in 1270, but died on the way at Tunis. This, the Eighth Crusade, was effectively the last. From now on, the pope would concentrate on promoting crusades against western heretics (the Albigensian crusade launched by Innocent III in 1209 against the Cathars of southern France set a bloody precedent) or against those who opposed the wishes of himself and his allies (the clergy could be taxed to pay for such ‘crusades’, and those who died received plenary absolution).

The Turks, after stemming the advance of the Mongol hordes (who at one point in 1241 raided to the borders of Hungary), picked off the Crusader strongholds one by one. Acre fell in 1300 and the Ottoman Turks got their first foothold in Europe at Gallipoli in 1354. Murad I (Shakespeare’s Amurath) set up a Turkish court at Adrianople, and though he himself was killed in battle against the Serbs under Prince Lazar Hrebeljanovic at Kossovo in 1389, the Serbs were defeated, and the Emperor John V asked the west for help. A large and splendid expedition led by John, son of the Duke of Burgundy, proved a fiasco and its army was annihilated at Nicopolis in 1396. The Turks were at the gates of Vienna, but a reprieve came in 1402 when they were set upon in the east by the Mongol Timur (Marlowe’s Tamburlaine) and the Sultan Bajezid I was killed. Constantinople was temporarily saved, but Byzantium was now no more than a Turkish vassal (only the Serbs held out) and the ‘fall’ of Constantinople in 1453 was like the falling of an over-ripe fruit.

The Holy Roman Empire, Italy, and the Papacy

The dissolution of empires is the story too in other parts of Europe, sometimes into elements that were to resist recomposition for many centuries, sometimes into the nation-states that first became recognisable in the later Gothic period. Central and central southern Europe had been ruled by the sprawling Holy Roman Empire in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, dominated by Germany, first under the Ottonian emperors and then under the Emperor Frederick I, Barbarossa (1152–90). Frederick had extended the effective powers of the Empire, as distinct from its nominal suzerainty, into northern Italy and even to Rome, where his challenge to the papacy, then at the height of its medieval power, over rights to the investiture of the clergy (and the claims meantime to the temporalities, that is, the profits from the lands and endowments accrued to that office) had ended inconclusively. But Frederick died by drowning on crusade in Asia Minor in 1190 and his successor, Henry VI, died in 1197, leaving an infant son, and the civil wars that followed tore Germany apart. That infant son, early crowned King of Sicily, became emperor as Frederick II in 1218, and Frederick had some success in reasserting imperial power, mostly from his base in southern Italy. He was skilful in his negotiations with the Muslim east when on crusade and had an unusual career as a patron of the arts and sciences, but his struggles to maintain imperial power in Italy against the papacy (he was frequently excommunicated by Gregory IX, pope 1227–41) were undone by his death in 1250.

| 1152–90 | Frederick I, Barbarossa, house of Hohenstaufen |

| 1190–97 | Henry VI, house of Hohenstaufen |

| 1198–1218 | NO EMPEROR |

| 1218–50 | Frederick II, house of Hohenstaufen |

| 1250–54 | Conrad IV, house of Hohenstaufen |

| 1254–73 | INTERREGNUM |

| 1273–91 | Rudolf I, house of Habsburg (not crowned) |

| 1292–98 | Adolf of Nassau (not crowned), deposed |

| 1298–1308 | Albert I, house of Habsburg (not crowned) |

| 1308–13 | Henry VII, house of Luxemburg |

| 1314–47 | Louis IV (Ludwig IV), King of Bavaria, house of Wittelsbach |

| 1347–78 | Charles IV, King of Bohemia, house of Luxemburg |

| 1378–1400 | Wenceslas (Wenceslas IV, King of Bohemia 1378–1419), house of Luxemburg |

| 1400–10 | Rupert of the Palatinate (not crowned) |

| 1411–37 | Sigismund, King of Hungary |

| 1438–39 | Albert II, house of Habsburg |

| 1440–93 | Frederick III, house of Habsburg |

Frederick II was succeeded as emperor by his eldest son Conrad IV (1250–54), but his illegitimate son Manfred inherited control of large parts of southern Italy. The Empire was in effect divided and, after the death of Conrad in 1254, for many years in disarray. The pope moved swiftly to expel the Hohenstaufens from the south and re-exert papal influence there: he invited Charles of Anjou, the brother of Louis IX of France, to take the throne of Sicily and Naples in opposition to Frederick’s son Manfred, thus beginning a century of Franco-papal alliance which was very deleterious to the authority of the papacy. Manfred died in 1266, and the last of the Hohenstaufens, Conradin, was executed by Charles of Anjou at Naples in 1268. The bloody rebellion of the ‘Sicilian Vespers’ in 1282, w...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- General Introduction

- Preface

- Notes On The Colour Plates

- List Of Abbreviations

- Acknowledgements

- 1 “Gothic Europe”: The Political and Economic Order

- 2 The Social Machinery of Cultural Production: Church, Court and City

- 3 The Gothic Achievement

- 4 Fragmentations

- 5 New Identities

- Glossary of Technical Terms

- Guide to Reading

- Index