![]()

1

Conceptualizing Rationality: Some Preliminaries

The issue of human rationality has provoked contradictory responses within the field of psychology. Some investigators eschew the term rationality and the attendant philosophical debates about normative criteria for thinking and advocate a purely descriptive role for psychology. In contrast, other investigators embrace the philosophical disputes about the normative criteria for evaluating human thought and view empirical findings as a vital context for these debates. In this volume, I throw in my lot with the second group of investigators. I demonstrate that certain previously underutilized aspects of descriptive models of behavior have implications for the evaluation of the appropriateness of normative models of rational thought. Yet assessing the degree to which humans can be said to be responding rationally remains one of the most difficult tasks facing cognitive science. Traditionally, philosophers have been more comfortable analyzing the concept of rationality than have psychologists. Indeed, psychological work that purports to have implications for the evaluation of human rationality has been the subject of especially intense criticism (e.g., Cohen, 1981, 1986; Gigerenzer, 1991b, 1996a; Hilton, 1995; Kahneman, 1981; Kahneman & Tversky, 1983, 1996; Macdonald, 1986; Wetherick, 1995). It is no wonder that many psychologists give the concept a wide berth.

The most intense controversies about human rationality arise when psychologists find that modal human performance deviates from the performance deemed normative according to various models of decision making and coherent judgment (e.g., expected utility theory, the probability calculus). Psychologists have identified many such gaps between descriptive models of human behavior and normative models. For example, people assess probabilities incorrectly, they display confirmation bias, they test hypotheses inefficiently, they violate the axioms of utility theory, they do not properly calibrate degrees of belief, they overproject their own opinions onto others, they allow prior knowledge to become implicated in deductive reasoning, they systematically underweight information about nonoccurrence when evaluating covariation, and they display numerous other information-processing biases (for summaries of the large literature, see Baron, 1994b; Dawes, 1988; Evans, 1989; Evans & Over, 1996; Osherson, 1995; Piattelli-Palmarini, 1994; Pious, 1993; Shafir & Tversky, 1995). Indeed, demonstrating that descriptive accounts of human behavior diverged from normative models was a main theme of the so-called heuristics and biases literature of the 1970s and early 1980s (see Arkes & Hammond, 1986; Kahneman, Slovic, & Tversky, 1982).

Although the empirical demonstration of the discrepancies is not in doubt, the theoretical interpretation of these normative/descriptive gaps is highly contentious (e.g., Baron, 1994a; Cohen, 1981, 1983; Evans & Over, 1996; Gigerenzer, 1996a; Kahneman & Tversky, 1983, 1996; Stein, 1996). Some psychologists have provoked the criticism that they were too quick to interpret the gap as an indication of systematic irrationality in human reasoning competence. It has been argued that the entire heuristics and biases literature is characterized by a proclivity to too quickly attribute irrationality to subjects’ performance (Berkeley & Humphreys, 1982; Christensen-Szalanski & Beach, 1984; Cohen, 1982; Einhorn & Hogarth, 1981; Hastie & Rasinski, 1988; Kruglanski & Ajzen, 1983; Lopes, 1991; Lopes & Oden, 1991). Critics argued that there were numerous alternative explanations for discrepancies between descriptive accounts of behavior and normative models.

In subsequent chapters, all of these alternative explanations are examined closely—but with a special focus. In this volume, I attempt to foreground a type of empirical data that has been underutilized by both sides in the debate about human rationality—individual differences. What has largely been ignored is that—although the average person in these experiments might well display an overconfidence effect, underutilize base rates, choose P and Q in the selection task, commit the conjunction fallacy, and so forth—on each of these tasks, some people give the standard normative response. It is argued that attention has been focused too narrowly on the modal response and that patterns of individual differences contain potentially relevant information that has largely been ignored.1 In a series of experiments in which many of the classic tasks in the heuristics and biases literature are examined, it is demonstrated that individual differences and their patterns of covariance have implications for explanations of why human behavior often departs from normative models.

In order to contextualize these demonstrations, however, I must make a number of conceptual distinctions. In the remainder of this chapter, a variety of useful distinctions and taxonomies are presented. I begin by adding the notion of a prescriptive model to the well-known distinction between descriptive and normative models.

DESCRIPTIVE, NORMATIVE, AND PRESCRIPTIVE MODELS

Descriptive models—accurate specifications of the response patterns of human beings and theoretical accounts of those observed response patterns in terms of psychological mechanisms—are the goal of most work in empirical psychology. In contrast, normative models embody standards for cognitive activity—standards that, if met, serve to optimize the accuracy of beliefs and the efficacy of actions. For example, in some contexts, subjective expected utility theory serves as a normative model for the choice of actions. Closure over logical implication is sometimes taken as a normative model of belief consistency. Bayesian conditionalization is often used as a normative model of belief updating. Much research accumulated throughout the 1970s and 1980s to indicate that human behavior often deviated from these normative standards (Evans, 1989; Kahneman et al., 1982; Pious, 1993).

As interesting as such divergences between normative and descriptive models are, they cannot automatically be interpreted as instances of human irrationality. This is because judgments about the rationality of actions and beliefs must take into account the resource-limited nature of the human cognitive apparatus (Cherniak, 1986; Gigerenzer & Goldstein, 1996; Goldman, 1978; Oaksford & Chater, 1993, 1995; Osherson, 1995; Simon, 1956, 1957; Stich, 1990). As Harman (1995) explained:

Reasoning uses resources and there are limits to the available resources. Reasoners have limited attention spans, limited memories, and limited time. Ideal rationality is not always possible for limited beings. Because of our limits, we make use of strategies and heuristics, rules of thumb that work or seem to work most of the time but not always. It is rational for us to use such rules, if we have nothing better that will give us reasonable answers in the light of our limited resources, (p. 178)

More colloquially, Stich (1990) noted that “it seems simply perverse to judge that subjects are doing a bad job of reasoning because they are not using a strategy that requires a brain the size of a blimp” (p. 27).

Acknowledging cognitive resource limitations leads to the idea of replacing normative models as the standard to be achieved with prescriptive models (Baron, 1985a; Bell, Raiffa, & Tversky, 1988; Simon, 1956, 1957). Prescriptive models are usually viewed as specifying how processes of belief formation and decision making should be carried out, given the limitations of the human cognitive apparatus and the situational constraints (e.g., time pressure) with which the decision maker must deal. Thus, in cases where the normative model is computable by the human brain, it is also prescriptive. In a case where the normative model is not computable (Oaksford & Chater, 1993, 1995), then the standard for human performance becomes the computable strategy closest to the normative model. Such a prescriptive strategy is the one that maximizes goal satisfaction given the individual’s cognitive limitations and environmental context. Thus, Baron (1985a) pointed out that:

[Although normative models may not provide] a good prescriptive model for ordinary people, it can be seen as a good prescriptive model for some sort of idealized creature who lacks some constraint that people really have, such as limited time. We may thus think of normative models as prescriptive models for idealized creatures …. A good prescriptive model takes into account the very constraints on time, etc., that a normative model is free to ignore, (pp. 8–11)

Baron also observed that “prescriptive models are, by definition, possible to follow, which is to say that there is in principle some way to educate people to follow them more closely than they do” (p. 10).

The distinction between normative and prescriptive models lies at the heart of debates about human rationality. It is often the case that investigators on different sides of the issue will agree that an accurate description of human performance deviates from the response dictated by a normative model but disagree about whether or not the response is consistent with a prescriptive model for the task in question. Investigators working in the heuristics and biases tradition (e.g., Kahneman et al., 1982; Nisbett & Ross, 1980; Tversky & Kahneman, 1974) have been prone to assume: (a) that the prescriptive model for most tasks was close to the normative model, (b) that the response that deviated from the normative model was thus also deviant from the prescriptive model, and thus, (c) that an attribution of irrationality was justified. Many critics of the heuristics and biases literature have tended to draw precisely the opposite conclusions—inferring instead: (a) that the prescriptive model for most tasks was quite different from the normative model, (b) that the response that deviated from the normative model was thus not deviant from the prescriptive model, and (c) that an attribution of irrationality was therefore unjustified.

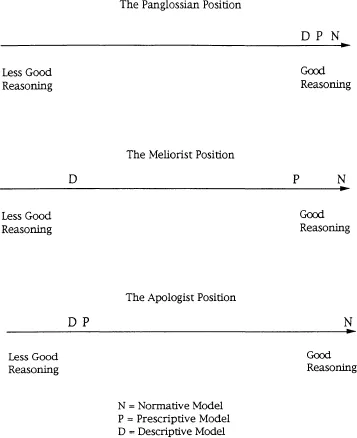

PRETHEORETICAL POSITIONS ON HUMAN RATIONALITY

There are three positions on the relationships between normative, prescriptive, and descriptive models that should be distinguished. These positions might be termed pretheoretical stances or preexisting biases because they largely determine how investigators approach the study of human rationality—determining the types of studies that they design and their data-interpretation proclivities. All three are illustrated in Fig. 1.1. Different relationships between normative, prescriptive, and descriptive models are illustrated as differing distances between the three on a continuum running from optimal reasoning to inefficacious reasoning. The position illustrated at the top is termed the Panglossian position, and it is most often represented by philosophers (e.g., Cohen, 1981; Dennett, 1987; Wetherick, 1995) who argue that human irrationality is a conceptual impossibility. For them, a competence model of actual human performance is coextensive with the normative model (and, obviously, the prescriptive as well). The Panglossian sees no gaps at all between the descriptive and normative.

Of course, in specific instances, human behavior does depart from normative responding, but the Panglossian has a variety of stratagems available for explaining away these departures from normative theory. First, the departures might simply represent performance errors (by analogy to linguistics, see Cohen, 1981 ; Stein, 1996)—minor cognitive slips due to inattention, memory lapses, or other temporary and basically unimportant psychological malfunctions. Second, it can be argued that the experimenter is applying the wrong normative model to the problem. Third, the Panglossian can argue that the subject has a different construal of the task than the experimenter intended and is responding normatively to a different problem. Each of these three alternative explanations for the normative/descriptive gap—performance errors, incorrect norm application, and alternative task construal—is the subject of extensive discussion in a subsequent chapter.

FIG. 1.1. Three pretheoretical positions on human rationality.

In addition to the philosophers who argue the conceptual impossibility of human irrationality, another very influential group in the Panglossian camp is represented by the mainstream of the discipline of economics, which is notable for conflating the normative with the descriptive:

The entire framework of economics—of whatever paradigm or in whatever application—rests on a fundamental premise, namely, that people behave rationally. By “rationally” I mean simply that before selecting a course of action individuals will consider the expected benefits and costs of each alternative and they will then select that course of action which generates the highest expected net benefit. (Whynes, 1983, p. 198)

Such strong rationality assumptions are fundamental tools used by economists—and they are often pressed quite far: “Economic agents, either firms, households, or individuals, are presumed to behave in a rational, self-interested manner … a manner that is consistent with solutions of rather complicated calculations under conditions of even imperfect information” (Davis & Holt, 1993, p. 435).

These assumptions of extremely tight normative/descriptive connections are essential to much work in modern economics, and they account for some of the hostility that economists often display toward psychological findings that suggest nontrivial normative/descriptive gaps. Yet there are dissenters from the Panglossian view even within economics itself. Thaler (1992) amusingly observed that:

An economist who spends a year finding a new solution to a nagging problem, such as the optimal way to search for a job when unemployed, is content to assume that the unemployed have already solved this problem and search accordingly. The assumption that everyone else can intuitively solve problems that an economist has to struggle to solve analytically reflects admirable modesty, but it does seem a bit puzzling. Surely another possibility is that people simply get it wrong. (p. 2)

That people “simply get it wrong” was the tacit assumption in much of the early work in the heuristics and biases tradition (e.g., Nisbett & Ross, 1980; Tversky & Kahneman, 1974)—and such an assumption defines the second position illustrated in Fig. 1.1, the Meliorist position. The Meliorist begins with the assumption that the prescriptive, if not identical to the normative, is at least quite close. However, the descriptive model of human behavior, in the Meliorist view, can sometimes be quite far from the normative. Because the prescriptive is close to the normative in this view, actual behavior can be quite far from the most optimal computable response (the prescriptive). Thus, the Meliorist view leaves substantial room for the improvement of human reasoning in some situations by reducing the gap between the descriptive and prescriptive. However, because this view posits that there can be large deviations between human performance and the prescriptive model, the Meliorist is much more likely to impute irrationality. The difference between the Panglossian and the Meliorist on this issue was captured colloquially in a recent article in The Economist (“The Money in the Message,” 1998) where a subheading asks “Economists Make Sense of the World by Assuming That People Know What They Want. Advertisers Assume That They Do Not. Who Is Right?”

A third position, pictured at the bottom of Fig. 1.1, is that of the Apologist. This position is like the Meliorist view in that it posits that there may be a large gap between the normative and descriptive. However, unlike the Meliorist, the Apologist sees the prescriptive model a...