Introduction

In this chapter, we demystify the concept of accountability. We proceed as follows: first, we present the prevailing views of accountability, highlighting notions of vertical, horizontal, diagonal, social and external accountability. We then link accountability to different forms of government—namely, presidential, semi-presidential and parliamentary. And finally, we highlight the different legislative oversight tools that are commonly adopted by legislatures operating in countries with different forms of government.

A central element of good governance is the question of how authority and power are allocated and applied in public life—the selection of political leaders and representatives, the provision of public goods and services, the rule of law and the stewardship of public resources, to name but a few. Generally, public officials—both elected and appointed—exercise varying degrees of power as they carry out their mandated duties. But what assures citizens that these officials will act in society’s best interests and not their own narrow self-interests? Democratic countries have established systems, procedures and mechanisms to promote the accountability of public officials to citizens; these accountability tools and processes both impose restraints on the power and authority of public officials and create incentives for accepted behaviors and actions (Brinkerhoff, 2001).

In recent years, the concept of public accountability has taken on heightened importance for two reasons. First, notwithstanding recent rollbacks, the state is playing a greater role in public and private life than ever before. And second, democracy has emerged as the most popular and aspired-to form of governance. Indeed, along with the concepts of transparency and representation/responsiveness, accountability is one of the central elements of democratic governance (World Bank, 1997).

Yet, despite its centrality to the notion of democratic governance, the notion of accountability is an amorphous concept that is difficult to define in precise terms. Indeed, the English word accountability, in its democratic and performance dimensions, does not readily translate into Spanish, Portuguese or French. In these languages, the word closest to accountability refers to the narrower concept of financial control and the reconciliation of budget expenditures and auditing.

However, broadly speaking, accountability exists when there is a relationship where an individual or institution, and the performance of tasks or functions by that individual or institution, are subject to another’s oversight, direction or request that the individual or institution provide information or justification for its actions.

Thus, the concept of accountability involves two distinct stages: answerability and enforcement. Answerability means having the obligation to answer questions regarding decisions and/or actions (Schedler, 1999). Two types of questions can be asked: the first is simply to be informed, which implies a one-way transmission of information from the accountee to the accountor. The second includes justification as to what was done and why (Brinkerhoff, 2001). Sometimes, the concept of answerability is referred to as “calling to account”, where the accountee to whom a task has been delegated is required to provide information about and explanation and justification of his or her activities (Blick and Hedger, 2008). Enforcement, by contrast, suggests that the public or the institution responsible for accountability can sanction the offending party or remedy the contravening behavior. Most people equate sanctions with requirements, standards and penalties embodied in laws, statutes and regulations, but sanctions also include softer enforcement mechanisms such as public exposure and negative publicity. Some analysts refer to this as “holding to account”, where, when the accountee is found to be at fault in some way, the offender is punished and/or victims compensated (Blick and Hedger, 2008). It should be noted that answerability without enforcement and sanctions without enforcement significantly diminish accountability. Nonetheless, different institutions of accountability might be responsible for either or both of these stages.

The concept of accountability can be classified according to the type of accountability exercised and/or the person, group or institution the public official answers to. Broadly speaking, there are four principal forms of accountability: horizontal, vertical and diagonal with a fourth type, social, being a particular case of diagonal accountability. All four types have emerged from different schools of thinking and little has been done to synthesize the different concepts. In recent years, bilateral donors and international aid agencies have added a new form of accountability: external or mutual accountability. There are conflicting definitions of what these various types of accountability are, resulting in a confused and disjointed literature and an associated difficulty in applying the concepts of accountability to practical governance issues.

One reason for this confusion is that the notion of accountability means different things in different political concepts. For example, the notion of ministerial accountability—a key concept in countries with parliamentary forms of government—is unknown in countries with presidential forms of government. Thus, accountability mechanisms that are appropriate and effective in parliamentary systems may be inappropriate and less effective in presidential or semi-presidential systems.

Prevailing View of Accountability

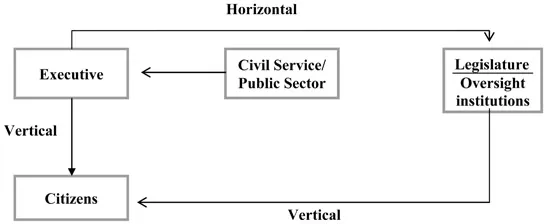

In 2011, we summarized the prevailing view of accountability (Pelizzo and Stapenhurst). We noted that horizontal accountability is where state institutions check abuses by other public agencies and branches of government, or is the requirement for agencies to report horizontally to other agencies. This concept has been examined by academics from the discipline of public administration. Conversely, the concept of vertical accountability, emanating from the political science and development disciplines, is the means through which citizens, mass media and civil society seek to enforce standards of good performance on officials (O’Donnell, 1999; Goetz and Gaventra, 2001; Cavill and Sohail, 2004).

Thus, executive governments (and other legislators as well) are held accountable by citizens via the electoral process; this is typically known as vertical accountability. Since elections are usually held every three to five years, in most countries other state institutions—notably the legislature but other institutions, too, such as ombudspersons and supreme audit institutions— hold the government to account on a day-to-day basis, via the concept of horizontal accountability.

According to this view, such institutions of accountability provide a network of relatively autonomous powers (i.e., other institutions) that can call into question, and eventually punish, improper ways of discharging the responsibilities of a given official. In other words, according to this view, horizontal accountability is the capacity of state institutions to check abuses by other public agencies and branches of government by requiring such agencies to report “sideways”. This is shown in Figure 1.1 by the relationship between the executive, the public sector and the legislature and other oversight institutions, where the latter, with the legislature, act as horizontal constitutional checks on the power of the executive.

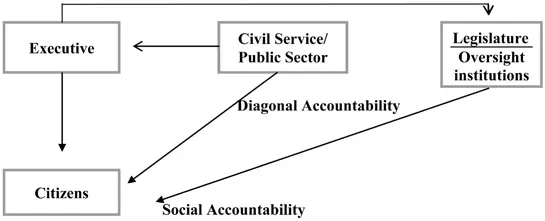

We also presented an extension of the traditional concepts of accountability and included the newer types of accountability—social and diagonal—highlighting the principal institutional actors and the accountability relations between them (Pelizzo and Stapenhurst, 2011). See Figure 1.2.

Social Accountability

The prevailing view of social accountability is that it is an approach toward building accountability that relies on civic engagement; namely, a situation whereby ordinary citizens or civil society organizations or both participate directly or indirectly in exacting accountability. Such accountability is sometimes referred to it as society driven horizontal accountability.

Figure 1.1 Prevailing Concepts of Accountability

Figure 1.2 Newer Concepts of Accountability

The term social accountability is, in a sense, a misnomer since it is not meant to refer to a specific type of accountability but rather to a particular approach (or set of mechanisms) for exacting accountability. Mechanisms of social accountability can be initiated and supported by the state, by citizens or both, but very often they are demand-driven and operate from the bottom up.

Social accountability initiatives are as varied and different as participatory budgeting, administrative procedures acts, social audits and citizen report cards, all of which involve citizens in the oversight and control of government. This can be contrasted with government initiatives or entities such as citizen advisory boards, which fulfill public functions.

The OECD’s Development Assistance Committees Governance Network (2010a) has pointed out that—regardless of form of government—the recent emphasis on social accountability has perhaps undermined state accountability. As a result, it is urging the strengthening of “bridging channels” that bring together both citizens and the state. The work of the Centre for the Future State, for example, has emphasized that support for a single set of accountability actors (such as CSOs) alone are not particularly effective. Rather, support should be given to help develop “broad passed alliances” that bring together a range of actors with common interests in reform and that cross the public-private divides.

In Uganda, for example, the USAID Linkages program aims to strengthen domestic linkages within the Parliament and between the Parliament, selected local governments and CSOs, as well as to build their capacities to improve service delivery and to enhance accountability (Tsekpo and Hudson, 2009). The program provides support to parliamentary committees and the shadow cabinet, including outreach through policy forums as well as funding CSOs to run local budget conferences to build citizen engagement in the budget process.

Diagonal Accountability

The prevailing view is that diagonal accountability entails vertical accountability actors. Generally speaking, diagonal accountability seeks to engage citizens directly in the workings of horizontal accountability institutions. This is shown in Figure 1.2 by the diagonal line linking citizens and the legislature and the secondary institutions of accountability. This is an effort to augment the limited effectiveness of civil society’s watchdog function by breaking the state’s monopoly over responsibility for official executive oversight.

The main principles of diagonal accountability are:

- Participate in Horizontal Accountability Mechanisms—Community advocates participate in institutions of horizontal accountability rather than creating distinct and separate institutions of diagonal accountability. In this way, agents of vertical accountability seek to insert themselves more directly into the horizontal axis.

- Information Flow—Community advocates are given an opportunity to access information about government agencies that...