- 148 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Occupational Therapy and the Patient With Pain

About this book

This volume speaks to the issue of occupational therapy practice with the patient in pain. The hows and whys of treatment are explored in a broad range of chapters written by and for professionals in the field of occupational therapy.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

MedicineSubtopic

Health Care DeliveryStress Management as a Component of Occupational Therapy in Acute Care Settings

Anne Affleck is Assistant Director of Physical and Occupational Therapy, Stanford University Hospital, Stanford, CA; Supervisor of Occupational Therapy; Part-time Instructor Occupational Therapy, San Jose State University. Elizabeth Bianchi is Staff Therapist, SUH; Graduate student, Occupational therapy, San Jose State University. Marlene Cleckley is Clinical Coordinator—Hoover Pavillion, SUH. Karen Donaldson is Staff Therapist, SUH; Graduate student, Occupational Therapy, San Jose State University. Guy McCormack is Assistant Professor, Occupational Therapy, San Jose State University; Relief Therapist, SUH; PhD Candidate. Jan Polon is Clinical Coordinator for Complex Case Teams, SUH.

ABSTRACT. The recent explosion of stress literature in the medical community has created a new awareness of “stress” as a potentially destructive force in itself. Contributing to physical and psychological dysfunction, stress has now been linked with a wide range of diagnoses including cancer, cardiac disease and arthritis. The importance of incorporating stress management activities into daily life is increasingly apparent. Occupational therapists concerned with patients’ ability to achieve health enhancing independent living skills are in a key position to help patients master stress management skills and incorporate them into activities of daily living. This article will explore the incorporation of stress management into occupational therapy programming for a variety of acute care patients. It will review the components of stress, the stress cycle, the relaxation response, the occupational therapy role based on a model of human occupation, and will review current programs through case study of four patients: one diagnosed with cancer (leukemia), one with anorexia nervosa, one with chronic pain and the fourth, a patient in medical intensive care.

One of the fundamental goals of occupational therapy at Stanford University Hospital is to enable patients to achieve effectiveness in the environment and mastery of life tasks. A concern for quality of life coupled with a sensitivity to the healing nature of purposeful activity has created in occupational therapy a focus on the use of activity to develop skills necessary for independent living and the management of meaningful life roles in work and leisure. But even in the context of meaningful activity, mastery is not easily gained. Almost all achievement includes an experience of stress, that is, tension, pressure or strain.1 The impetus to grow, to learn, the stimulus of school, the inner drive of the child to explore can all be seen as stresses. They are pressures inching a system toward positive change. Stress, however, can reach a critical tension, no longer positive when pressure and demand for change temporarily overwhelm the individual’s capacity to adapt. Dysfunction, physical, psychological or both, is the result.

Occupational therapy intervention with patients under stress is not new. Common sense acknowledges the extreme emotional stress of serious illness, the physical stress of pain, the environmental stress of the sterile, white hospital. The recent explosion of stress literature in the medical community, however, has created an awareness of “stress” as a potentially destructive force in itself, manifesting an array of physical and psychological illnesses including cancer,2 arthritis,3 and cardiac disease.4 With this increase in information, occupational therapists are now able to more completely consider stress management a life skill, incorporating stress management activities into activities of daily living, exploring stress management as a component of independent living and competent role management. To begin this process, this article will review the components of stress, the stress cycle, intervention to manage stress, occupational therapy role and program models through case presentation.

Stress-Com Ponents and Responses

Stress may be viewed as a composite of the physical, emotional and environmental factors. By far the greatest physical stress encountered is pain. Physiologically, pain is a signal which informs us about potentially harmful stimuli. Eight of the most common pain syndromes treated in the medical setting represent the terrible scope of the pain experience. They are:

- Vascular pain resulting from dilation of blood vessels in the periphery or the dura mater of the brain;

- The muscle and joint pain of inflammatory processes or structural damage: including arthritis, bursitis, tendonitis, inter-vertebral disc disorders, low back syndrome and temporomandibular joint problems;

- Causalgia, intense burning pain resulting from trauma to peripheral nerves;

- Neuralgia, sudden, excruciating pain usually arising from the sensory neurons in the trigeminal nerve distribution of the facial region;

- Terminal cancer pain generated by tissue destruction or obstruction of major organs;

- Thalamic syndrome in CVA, the drastic lowering of pain threshold on the hemiparetic side of the body;

- Phantom limb pain resulting from neuromas, scar formation, bone spurs or poorly understood descending pain messages arising from the brain;

- And finally, post-surgical pain, especially in the abdominal region.5-9

Emotional pain is no less formidable. Like physical pain it varies greatly in intensity. It ranges from loss of reality contact, to grief, fear of an uncertain future, to material worries such as getting to the bathroom or paying the bills. Underlying both physical and emotional stress can be the pain of coping with a disorganized, unfamiliar or an extremely demanding environment. Intensive Care Units (ICU) exemplify such environmental stress with 24 hour light, noise, activity and bodily “invasion” of the patient. What is common to all faces of stress: physical, emotional, environmental and especially to combinations of these factors, is that they can elicit in a person the stress response.

The stress response is the result of behaviors learned early in life for coping with difficult and painful experiences. On the most primitive level, stress is perceived by the systems as a threat to its existence and leads to the flight or fight response. The body’s regulating system then gives the order to increase metabolic rate in preparation to confront or escape threat. Physical manifestations of the flight or fight response include: increased heartbeat, a rise in blood pressure, rapid shallow breathing, release of adrenalin and other hormones, pupil dilation, tensing of skeletal muscles for movement, the constriction of blood flow to digestive organs and extremities, increased blood flow to the brain and major muscles, increased perspiration and release of stored sugar from the liver for energy.10 If the body is not given relief from the biochemical changes that occur during fight or flight, a state of chronic stress is the result. Chronic stress or a prolonged state of threat causes damage to the body and potentially system deterioration and death. It is important to remember that emotional responses to stress can trigger the same or similar physical changes as fight/flight responses do in more life threatening situations. Hence, emotional stress becomes a cause of physical illness, pain and more emotional stress and the vicious cycle is established.

Interventions

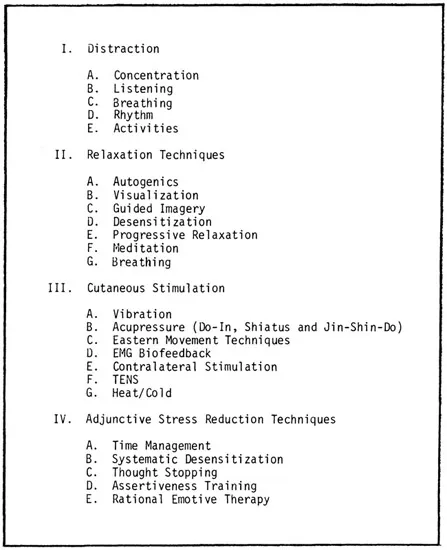

Medical science and psychiatry have a long history of response to stress related illness. Much of physical and psychological pain has been managed with an array of pharmacological agents such as analgesics, antispasmodics, sedatives, tranquilizers, narcotics or anti-psychotics. In severe cases neurosurgical or abative procedures have been used. However, less drastic, non-invasion techniques are also available. Many of these are noted in Figure 1.

All of these non-invasive stress management techniques are used to induce a relaxation response. The relaxation response counteracts chronic stress by returning the body to its natural state of physical, emotional, and mental balance. This response is characterized by: decreased oxygen consumption, decreased respiratory rate, decreased heart rate, increase in alpha brainwave, decreased blood pressure, decreased muscle tension.10 If the relaxation response can be elicited it becomes possible to break the chain of destructive physiological changes that occur in stress.

Occupational Therapy

Using the Kielhofner-Burke11 model of human occupation one can consider that the occupational therapist’s point of intervention for patients with stress related problems rests in the skill building or performance sub-system. The occupational therapist helps patients to develop skills upon which they can build habits of living consistent with their goals and the demands of the environment. Occupational therapy seeks, through the use of purposeful activity, to reverse vicious, and support benign cycles of adaptation.

FIGURE 1

The tools of the therapist are activity analysis and patient evaluation. The safe and effective use of stress management techniques in a therapeutic setting requires careful assessment of the patient’s strengths and needs. Before choosing an activity a therapist needs to know the patient’s status with regard to sensory, motor, cognitive, psychological and social functioning.12 The activities themselves must be scrutinized to assess the demands they place on patient systems. Options for activity modification must be considered. With a goal of initiating a benign cycle of adaptation, occupational therapy treatment begins activity programming with a match between patient skill level and activity demand. For example, in using relaxation techniques, or mental activity with a patient who has a history of psychosis or poor ego boundaries, the therapist uses activities such as progressive relaxation or autogenics which heighten body awareness and attention to the present reality. Visualization and guided imagery, both non-reality based methods, would be avoided. Conversely, the patients with pain or severe somatic complaints may use more effectively the techniques which draw their attention away from physical sensation and the “offending” body part. Visualization, guided imagery and/or craft activities may later be varied and graded to expand the skill base in any deficit area affecting personal independence and life satisfaction. For example, the resting and emptying of the mind implied in meditation may be precisely the need of the colitis patient experiencing anxiety attacks. However, such a patient may lack the physical control and ability to concentrate required by such an activity. Starting with breathing and a rhythmic sport such as swimming may be an effective alternative in building tolerance for relaxation and control of anxiety. Learning new skills, and experiencing success will allow the system to become self-regulating, versatile and independent. An examination of specific program models and case studies will be used to demonstrate the application of these principles.

Program Models

Intensive Care

Requisites for admission to intensive care (ICU) at Stanford University Hospital include patient’s need for invasive monitoring of vital systems, 12 hours/day nursing care, peritoneal dialysis or mechanical ventilation. Medical conditions that potentially create this demand are many, including adult respiratory distress syndrome, major surgery such as open heart or organ transplant, or vital system failure. In addition to experiencing an acute life threatening illness, the intensive care unit creates a challenge to patient adaptability. The ICU presents the patient with all of the four major components of the low stimulus environment.13

- Sensory deprivation or lack of visual, auditory, tactile and kinesthetic input;

- Perceptual deprivation or meaningless or unpatterned visual and auditory stimuli;

- Immobilization: severe restriction of freedom of motion;

- Social isolation: monotony and lack of social contacts.

The effects of such environments on people may include loss of motivation, impaired ability to concentrate, to maintain thought, to reason and problem solve; impaired visual perception processing and decreased dexterity.14 Emotional states of anxiety, anger, guilt, shame or depression often parallel a sensory deprivation experience. The delusions and hallucination characteristic of patients in low stimulus environments may be a component of perceptual dysfunction. Zuckerman notes the system’s effort to remain integrated by providing itself with internal stimuli to which it may respond in the event of environmental impoverishment.14

Another major stress of the ICU experience is that of ventilator weaning. The goal of mechanical ventilation at the onset of treatment is to stabilize the patient hemodynamically by adjusting the number of mandatory breaths per minute, percentage of oxygen received and the amount of pressure offered by the ventilator.15 Once the patient’s blood gases are stable, the goal is to slowly reduce mechanical intervention and oxygen support until the patient can breathe independently again. The process must be slow in order to allow the body to accommodate to fewer breaths and to lower oxygen concentration. The process is described by patients as physically tiring and emotionally stressful due to the resultant sensation of breathlessness or “air hunger”. Since a fight or flight response during a period of air hunger would only increase oxygen demand and exacerbate shortness of breath, it is important to help the patient develop skills to cope to the rising sense of panic that breathlessness induces.

Awareness of the effects of low stimulus environment is most powerful when juxtaposed to the literature regarding the role of activity in coping with a stressful situation. Gal and Lazarus cite the importance of activity in enabling persons under stress to achieve a sense of mastery, and through this experience of personal effectiveness, to cope with even life-threatening situations more skillfully.16 In viewing activity as a coping mechanism two major goals were noted: (1) activity directed toward dealing with the threat and (2) non-related activity performed in anticipation of stress. “Directed activity” in occupational therapy can be seen in tasks of daily living or crafts used specifically to increase strength, endurance or to enhance recovery. “Non-related” activity includes use of hobby, craft or relaxation exercises prior to an unpleasant procedure such as chemotherapy. It seems that depending on personality and context, distraction and/or direct effort to act upon stress can be helpful in enhancing a patient’s sense of efficacy and ability to manage stress. The extreme inactivity imposed on the patient in the low stimulus environment of intensive care contributes further to vicious cycles of deprivation, disorientation and disengagement from life.

From this knowledge of the patient experience in ICU, the role of occupational therapy can be developed.

In general the therapist works:

- To reduce the damaging effects of low stimulus environment through sti...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

- FROM THE EDITOR’S DESK

- FROM ANOTHER PERSPECTIVE: A CLINICIAN’S VIEW OF THE THEME

- Occupational Therapy and the Patient with Pain

- Stress Management as a Component of Occupational Therapy in Acute Care Settings

- Occupational Therapy Intervention in Chronic Pain

- Perspectives on the Pain of the Hospice Patient: The Roles of the Occupational Therapist and Physician

- The Schultz Structured Interview for Assessing Upper Extremity Pain

- Shoulder Pain in the Patient with Hemiplegia: A Fundamental Concern in Occupational Therapy

- The Role of Occupational Therapy in Back School

- The Use of Biofeedback Techniques in Occupational Therapy for Persons with Chronic Pain

- The Use of Assertiveness Training with Chronic Pain Patients

- The Growth of the Hospice Movement: A Role for Occupational Therapy

- PRACTICE WATCH: THINGS TO THINK ABOUT

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Occupational Therapy and the Patient With Pain by Florence S Cromwell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Health Care Delivery. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.