Introduction

Elderly people will present a larger portion of the population in the coming decades because of increased life expectancy in the general population. A possible implication is that the elderly may be more likely to become victims or witnesses of certain types of crimes than in earlier decades (e.g., Dunlop, Rothman, & Hirt, 2001), unless fear of crime makes them avoid public contact. Consider the following example:

In November 1980, a 66-year-old woman woke up in her bed while a man was assaulting her. His face was covered with a stocking mask; he wore a cap, gloves, and a coat. She was hesitant to describe or identify her assaulter. Tips from informants led the police to a man called Willie Davidson. When the victim was shown a photo array with Davidson in it, she recognized him as a person who had visited her 1 day before the attack. The next day, she reported to her daughter that she was sure that he was the assaulter. The police then put a stocking on Davidson’s head and asked the victim to identify him, which she did. As a result of eyewitness misidentification, improper forensic science, and ignorance of his alibi, Davidson was convicted and sentenced to 20 years and was released from prison after 12 years. After a DNA test was negative, Davidson was granted a full pardon. He had served 12 years for a crime he did not commit. (For a full case description, see The Innocence Project, n.d.-b)

Besides government misconduct, this case demonstrates many factors likely to affect eyewitness identification as a function of old age: fallibility in memory, poor recognition memory, source monitoring deficits, suggestibility, acquiescence, and perhaps a personal motive to punish someone. This chapter describes these and other factors associated with old age and identification accuracy.

Definition of Old Age

In the gerontology literature it is customary to treat “old age” not as a single category but to refer to different groups of elderly, sometimes labeled young-old, middle-old, and old-old. Unfortunately, most studies in the psychological literature reviewed in our two meta-analyses did not converge on any such definitions, although some individual studies did differentiate subgroups of elderly as young-old or old-old. In our meta-analyses, studies were included when direct comparisons between a group of young participants (usually in their early 20s or between 20 and 30 years old) and a group of elderly participants with a minimum mean age group of 60 years or older were included. We provide additional details for our meta-analyses subsequently and mention the respective age definitions when discussing individual studies. Toward the end of this chapter, we graphically presenting results as a function of mean ages of the elderly groups to demonstrate the continual nature of the old age effect discussed here.

In the psychology of memory literature, natural aging is associated with changes in memory performance. This starts with reduced encoding of incoming information due to decreasing functioning of sensory organs with aging. One reason is the physiological changes of the eyes—for example, the increased rigidity of the iris and the lens, reduced pupil diameter, or the increased likelihood of cataracts (Kline & Scialfa, 1996). In addition, the elderly seem to record fewer visual stimuli than young people in the same time (Mueller-Johnson & Ceci, 2007; Yarmey, 1996).

Further, from a neuropsychological perspective, structural changes of the brain cause changes in memory function (Moulin, Thompson, Wright, & Conway, 2007). A decrease of brain volume was shown at around 0.22% per annum from the age of 20 up to 80 years by Fotenos, Mintun, Snyder, Morris, and Buckner (2008) in a cross-sectional and longitudinal study with 18-to 97-year-old participants. In particular, changes of the frontal lobe are important for eyewitness research (Moulin et al., 2007). Frontal lobe damage causes deficits in free recall of events and in the ability to correctly monitor sources as well as in meta-memory, which depicts reflections about one’s own memory (Mayes, 2000). However, this may not impact recognition because recall and recognition represent two different systems (Tulving, 2000). While recall requires free reproduction of memory contents, for example, of an event or person, recognition involves the correct discrimination of items between new and old items, that is, the culprit in a lineup. Furthermore, for person identification, recognition is not sufficient but must be linked with the circumstances of encounter (the scene of the crime), which in essence is a source-monitoring problem.

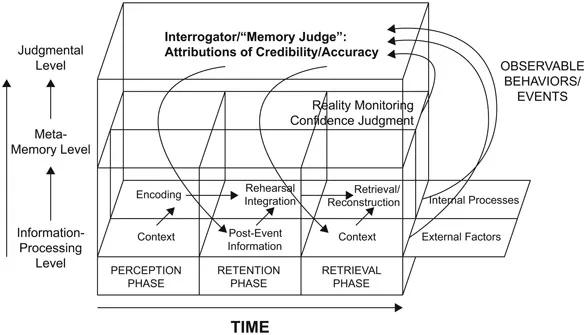

Furthermore, natural aging causes changes in information processing, working memory capacity, inhibition of irrelevant information, and deterioration of long-term memory (Park & Reuter-Lorenz, 2009), specifically episodic memory (e.g., Naveh-Benjamin, Guez, Kilb, & Reedy, 2004). Aging processes are associated with a continuous decrease of processing speed, working memory, and short- and long-term memory but also with a lifelong increase of knowledge-based verbal ability (e.g., in vocabulary), as demonstrated by Park et al. (2002) in a study of 345 people ranging between 20 and 92 years. Support for an increase in verbal fluency also comes from a recent study with participants aged between 17 and 78 years in which verbal fluency, in particular letter fluency, improved when changes in processing speed were controlled for (Elgamal, Roy, & Sharratt, 2011). However, such findings may be moderated by educational opportunities that some elderly cohorts (e.g., in the post–World War II period) may not have had. Considering that person descriptions and identification show only small correlations (see the meta-analysis by Meissner, Sporer, & Susa, 2008), verbal abilities are unlikely to be associated with person identifications but may become relevant when evaluating elderly witnesses present their testimony before court (see Figure 1.1 and the last section of this chapter).

Another important aspect of aging is the reduced capacity to inhibit irrelevant information (Hasher & Zacks, 1988). Thus, older adults show deficits and slowing in working memory as well as slowing due to inaccurate selection of relevant and irrelevant information and inefficient removal of no longer needed content (Park & Reuter-Lorenz, 2009). To what extent this deficit also affects a witness in an identification task is an intriguing question, particularly with a larger number of foils (as is common in Great Britain).

Age-related memory differences are postulated to go along with a decrease of controlled memory processes, whereas automatic memory processes remain intact (Jennings & Jacoby, 1993). In contrast to an unimpaired memory, this results in aggravated information processing. This affects both the memory of relevant situational characteristics as well as of variations of familiar stimuli. Consequently, older people are more likely to be susceptible to changes in the context of the stimuli presented (faces). Furthermore, older people’s ability to distinguish between internal and external memory contents is more limited, and thus the ability to correctly identify the origin of a memory. Research has shown that people have difficulty matching the source of a memory correctly, especially with thematically similar information (Lindsay, Allen, Chan, & Dahl, 2004). This seems to affect above all older adults (over 65 years), who were shown to be more suggestible to misleading information than their younger counterparts (e.g., Cohen & Faulkner, 1989; Loftus, Levidow, & Duensing, 1992; see also Bornstein, 1995).

Eyewitness Recall and Recognition

When people become witnesses to a crime, they have to decide whether to report it to the police, and if yes, when. Whether the elderly report crimes more frequently than younger people is an interesting question of its own but is beyond the scope of this chapter. If witnesses do decide to report a crime they will be questioned by the police about the event as well as about the perpetrator or perpetrators involved. Witnesses usually start with a free narrative—referred to as free recall by memory researchers—followed by more specific questions referred to as cued recall. They may also be asked to create an image of the perpetrator with a police sketch artist or with computerized face composite systems like FACES or Evofit (see Davies & Valentine, 2007). Besides descriptions of the perpetrator, witnesses also may be asked to identify a suspect from a photo spread (or a live lineup). From a memory perspective, this is a recognition task that has received considerable attention in the eyewitness literature. The focus of this chapter is a review of person identification and face recognition studies that have investigated differences between elderly and young people. These differences may be affected by factors operating at the perceptual stage, during the retention interval, or at the recognition phase.

An Integrative Model of Eyewitness Testimony

Both legal scholars and eyewitness testimony researchers have divided the cognitive and social processes as well as the factors affecting eyewitness testimony into three stages (Loftus, 1979; Sporer, 1982, 1984; Yarmey, 1979): (a) an acquisition, perception, or encoding stage, (b) a retention interval, and (c) a reproduction, recall, or recognition phase. Figure 1.1 displays an integrative model of eyewitness testimony proposed by Sporer (2008).

Figure 1.1 Integrative model of stages and processes involved in eyewitness testimony (from Sporer, 2008).

At encoding, differences may emerge in the amount of information processed by elderly compared with young witnesses. A host of so-called estimator variables may affect later identification outcomes, for example, the stress and arousal experienced in a crime situation, the length of exposure to the target, or the time of day. Some of these factors may affect the elderly more than younger participants. For example, the elderly categorize themselves more frequently as “morning people” (which is supported by differences in circadian rhythms), which may put them at a disadvantage for crimes experienced at off-peak times (see Mueller-Johnson & Ceci, 2007, for review, and Diges, Rubio, & Rodriguez, 1992, for an early study of time of day effects with young adults).

Forgetting during the retention phase may affect memory of the elderly differently than that of younger people. At the retrieval phase, factors affecting performance of eyewitnesses, such as the use of unbiased versus biased instructions, or the presentation form of identification lineups (simultaneous vs. sequential) may also differentially affect the elderly compared with the young.

Besides these three stages along the time continuum, we can also distinguish between different levels of information processing, particularly at the retrieval stage. Although most researchers have focused on the factors that determine the accuracy of recall and recognition at this stage, there is also a large body of research on the meta-memorial processes that accompany these retrieval processes. In particular, the expressed confidence accompanying recall and/or recognition may or may not be a reliable indicator of the accuracy of the details reported or of the accuracy of an identification. Elderly people may differ from younger ones not only by the amount and accuracy of their memory retrieval products but also in the confidence associated with these answers.

At the judgment level, agents of the criminal justice system (police officers, attorneys) and triers of fact (jurors or judges) evaluate witness statements, having to decide whether they are reliable enough to base their decisions on them (e.g., pursue the prosecution of a suspect further, or decide on the guilt or innocence of a suspect). These evaluation processes are not only influenced by the witness statements as such but also by verbal utterances about meta-memorial processes and the accompanying nonverbal behavior.

The purpose of this review is not to describe the factors that determine the relevant cognitive processes at the three stages at the three different levels but to focus on research findings that point to differences in these processes between people at old age and younger people. These differences may emerge in two ways: as main effects, that is, better recognition performance of younger people compared with the elderly, and as interactions between determinants of eyewitness testimony and age of witness, that is, certain factors may affect eyewitness identifications of old people differently than those of young people.

In the next two sections, we describe the different methods and paradigms researchers have used to study person identification and face recognition as well as specific methodological issues involved in these general paradigms.