![]()

1. Introductory Section

A. Overview chapters: The context in which this book was prepared

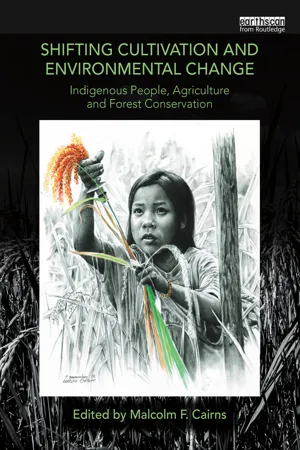

An elder from an Akha Panghok swidden-farming community in mountainous northern Laos draws thoughtfully on her pipe as she regards a foreign visitor

Sketch based on a photo by Laurent Chazée

(i) A backwards glance, over our shoulders ...

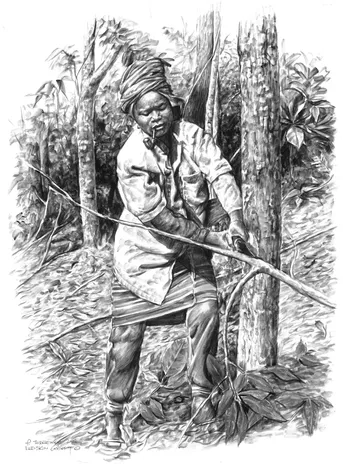

According to Lawa tradition, when clearing a swidden, the actual tree-cutting is done by women

Sketch based on a photo by Dietrich Schmidt-Vogt

![]()

1

The View of Swidden Agriculture

By the early naturalists Linnaeus and Wallace

Michael R. Dove*

Introduction

The academic literature on swidden agriculture remains as robust as ever, re-stimulated, in part, by burgeoning interest in climate change-related REDD schemes (for Reduced Emissions from Degradation and Deforestation, e.g. Hett et al., 2012). REDD is not the only current, intellectual driving force. Other interests of contemporary swidden researchers include swidden fallow management, which has generated a considerable literature (Cairns, 2007), the related topic of biodiversity in swidden systems (Padoch and Pinedo-Vasquez, 2010), and continuing interest in the role of swidden systems and societies in wider economic (Dove, 2011) and political (Scott, 2009) circles. Interestingly, in spite of half of a century of focused study, and an additional prior century of observation by travellers and colonial officials, a number of prominent contemporary researchers still identify our lack of knowledge of swidden as a problem. For example, Mertz et al. (2009, p262) wrote of Southeast Asia:

Despite a relatively large number of cases from the region, the knowledge of swidden cultivation is still very patchy and many essential elements such as exact areas affected and people involved are not well documented. The general drivers of swidden change are somewhat better understood, but data on their relative importance in many regions still elude us.

In order to document changes in swidden systems, their extent must first be known, and Padoch et al. (2007) examine the reasons why even this baseline information is still hard to come by.

Some of these same questions have dogged studies of swidden agriculture throughout the modern history of such study, as exemplified by the mid-18th-century work of Carl Nilsson Linnaeus, specifically his 1751 Skånska Resa (Scanian Travels), and the mid-19th-century work of Alfred Russel Wallace, referring to his 1869 The Malay Archipelago. Linnaeus (1707-1778), known as Carl von Linné after he was knighted for his work, is known to us as the father of modern taxonomy and the system of binomial nomenclature. Wallace is known to us as one of the founders of the field of biogeography (with his ‘Wallace’s Line’) and especially as the man whose independent development of the theory of evolution based on natural selection prompted Darwin to publish his own views, to greater, and lasting, public acclaim.

Neither Linnaeus nor Wallace are known for their scholarship on swidden agriculture and, indeed, few modern scientists are even aware of it. But both men did examine swidden agriculture, and both had prescient things to say about it. Revisiting what they said puts current practices of swidden agriculture into historic perspective and, of equal importance, it puts into perspective our study of swidden and the enduring problems of the politics of knowledge and the divide between nature and culture. The ability of Linnaeus and Wallace to comprehend the dynamics of swidden systems in the face of historic and enduring biases illuminates the epistemology of swidden agriculture; and their ability to appreciate the value of swidden landscapes illuminates the stark, modern dichotomy between society and environment and the blinkers it imposes on us. In the following analysis, I will review the swidden-related work of first Linnaeus and then Wallace. In each case, I will place their observations in historic, social, political and intellectual context. I will conclude with some suggestions as to what this study tells us about the global history of swidden agriculture, the historic construction of ignorance regarding it, and the implications of a less- versus well-developed Cartesian divide of nature and culture.

Linnaeus

Whereas the popular contemporary image of swidden agriculture locates it firmly in a tropical, non-Western context, the work of Linnaeus joltingly reminds us of a temperate-zone, Western history (Figure 1.1). The 20th-century accounts of swidden systems, which typically note how different they are from Western systems of agriculture and how much of a mental contortion Westerners must go through in order to appreciate them, depend on a curious forgetting of Western history — and not remote history, either. Swidden cultivation remained economically preferable to working in industry in parts of France until around 1890; and pockets of swidden remained in Germany, Austria and northern Russia until the 1950s and 1960s (Sigaut, 1979). In North America, a swidden system based on some melding of European and Native American practices developed in the southern uplands, where it dominated through the 19th century and remnants of it persisted well into the 20th-century (Otto and Anderson, 1982).1 Swidden cultivation may have endured longest in some of the less-populated and less-industrialized parts of Scandinavia, the swidden history of which has attracted a fair amount of recent scholarly attention (Lehtonen and Huttunen, 1997; Emanuelsson and Segerström, 2002; Myllyntaus et al., 2002). Certainly, swidden agriculture was still widely practised in Sweden, if often surreptitiously, in the mid-18th century, when Linnaeus studied it.

FIGURE 1.1 Carl von Linné, aka Carl Nilsson Linnaeus, from an engraving by the artist Lizars, wearing Lapland dress and holding a plant, with instruments around his waist

Source: History of Medicine Division,

US National Library of Medicine

Linnaeus’ ‘Scanian Travels’

In the course of his professional career, Linnaeus undertook a number of celebrated expeditions to lesser-known regions of Sweden, where he carried out natural history studies of both the environment and human society. The last of these, undertaken at the behest of the Swedish government in 1749, was to the province of Skåne, or Scania, in southern Sweden. This trip, like those he had previously carried out to Lapland, Dalecarlia, and the two Baltic islands of Öland and Gotland, was selfconsciously driven by a patriotic naturalist curiosity. As Linnaeus noted when he gave his inaugural lecture at Uppsala University, ‘Good God! How many, ignorant of their own country, run eagerly into foreign regions, to search out and admire whatever curiosities are to be found; many of which are much inferior to those which offer themselves to our eyes at home’ (Stillingfleet, 1759). Scania had been part of the Kingdom of Denmark until 1658, and was politically unstable until 1720, when its classification as a conquered foreign land was finally relinquished and it was officially made part of Sweden proper, although a policy of forced cultural assimilation continued for another century. In addition, many of the upland swidden farmers of this and other parts of Sweden were an ethnic minority, the immigrant ‘forest Finns’, who had historically been encouraged to clear the country’s forests, but by Linnaeus’ time were seen as despoilers of natural resources.

In the account of this trip, published in 1751 as Skånska Resa (Skåne Journey or Travels), Linnaeus offered detailed observations of flora and fauna and also land uses, in particular the then ubiquitous practice of swidden cultivation, obtained in part through interviewing the local people. As he wrote, ‘Burn-beaten areas, which are everywhere seen among the forests here in Småland, and which are looked upon by some as profitable, by others as rather deleterious, were closely examined and the benefit and the injury done to the countryside were weighed against one another’ (Linnaeus, 1751, p26, cited in Weimarck, 1968, p56).2 The term ‘burn-beating’ is a translation of the Swedish term svedjebruk, which refers to the practice of swidden agriculture (Weimarck, 1968).3 In districts unsuited for intensive agriculture, Linnaeus saw distinct advantages to burn-beating:

[W]hen one looks upon the forests in stony Småland, where woodland is extensive, one sees the most unpromising surface, covered with small stones and overgrown with heather, which can hardly be changed for the better; when the farmer here cuts down the trees and burns the land by burn-beating, he obtains from his otherwise quite unprofitable forest and soil, a mostly fine grain, and for several years after that a good pasture of grass, which comes up between the stones, until the heather once more chokes the grass. Pine and spruce soon re-establish themselves, so that after 20 to 30 years they are ready for new burn-beating. In this way the farmer gets an abundance of grain from otherwise quite worthless land. (Linnaeus, 1751, p26, cited in Weimarck, 1968, p56)

He concluded with a staunch endorsement of the economic importance of burn-beating to the rural populace of the province:

If the inhabitants of Småland were not allowed to have burn-beating, they would want for bread and be left with an empty stomach looking at a sterile waste, with expectations after a couple of hundred years for their own, or for other’s descendants, who could, however, scarcely hope to reap any harvest from a thankless soil and stony Arabia infelix. (Linnaeus, 1751, p26, cited in Weimarck, 1968, p56)

Linnaeus’ reference to non-burn-beaten land as ‘sterile waste’ and ‘stony Arabia infelix’ is notable, coming as it did from Sweden’s most famous naturalist. It reflects an absence of discrimination between ‘natural’ and ‘human-altered’ landscapes that seems odd from our contemporary standpoint. As Koerner (1999, p84) wrote, Linnaeus actually ‘preferred bucolic culturescapes to pristine nature’ and ‘could not imagine a fundamental conflict of interest between nature and humankind’.

Linnaeus’ observations are valued today for the insight that they give into the conditions at the time. As Jackson (1923, pp208-209) wrote, ‘These statements are a gold mine for the present-day student in acquiring a knowledge of Sweden gleaned from the country folk in the middle of the eighteenth century’. Weimarck (1968, p11) similarly wrote: ‘In his Scanian Travels, Linnaeus (1751) gives an authentic description of the agriculture [in the region].’ Weimarck carried out extensive studies of environmental history in northeast Scania in the mid-20th century, in a district much like that described by Linnaeus, on the basis of which she utilized, clarified and expanded on his findings. She began with the remarkable statement: ‘[A]ll naturally well-drained mineral soils (viz., all areas suitable for agriculture) within these investigated areas have on some occasion been subject to burn-beating’ (Weimarck, 1968, p7). Based on her analysis of archival forestry records for one particular parish, Weimarck (1968, pp35, 37) found that in 1842, almost a century after Linnaeus’ observations, burn-beating was still the ‘principal livelihood’ of the rural inhabitants. She found that this condition persisted until the end of the 19th century:

My research has shown that in South Sweden the country people living in the thinly populated hilly forest-clad land, covered with principally Archaean rock materials since ancient times and until nowadays, about 1900, have had their principal livelihood from burn-beating, carried out in the enclosed meadows, in the enclosed pasture lands and in the forest land. (Weimarck, 1968, p52)

Burn-beating

Weimarck (1968, p13) described this historic agricultural system as follows: ‘[B]urn-beating means that each year a new area of woodland is taken into circulation and that each year a corresponding area is abandoned to revert to natural growth.’ The burn-beaten lands were subjected to a multi-year cycle or rotation, with the more demanding land uses (in terms of need for nutrients and weeding) staged earlier and the less demanding staged later, just as has been reported of swidden systems in other parts of the world. The cycle consisted of: (1) clearing and burning the forest (not necessarily in the same year); (2) cultivating turnips; (3) cultivating rye; (4) cultivating hay; (5) managing as pasture, and (6) relinquishing to natural afforestation (Weimarck, 1968, p52). Linnaeus, as noted earlier, reported that the fallow period averaged 20 to 30 years; his contemporary Krook (1765, cited in Weimarck, 1968, p43), put it at 30 years (see Figure 1.2).

The productivity of this agricultural system was high, which is consistent with findings from studies of swidden systems around the world. For example, Öller (1800, cited in Weimarck, 1968, p46) reported that burn-beating yielded a return on sown seed of 16-24/1, which far surpassed contemporaneous yields of 2-5/1 in tilled fields (and is in the same order of magnitude as the return of 12-20/1 reported by Dove (1985) in West Kalimantan, Indonesia, or 48/1 reported by Conklin (1957) in Mindoro, the Philippines). Another way of characterizing the productivity of burn-beating is simply to say that it was not onerous (cf. Dove, 1983). As Krook (1765, cited in Weimarck, 1968, p43) put it, ‘[T]hey in this way got a greater yield with comparatively little work.’ As reported by Weimarck in the m...