eBook - ePub

The Bomb

Nuclear Weapons in their Historical, Strategic and Ethical Context

- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Bomb

Nuclear Weapons in their Historical, Strategic and Ethical Context

About this book

This tightly argued and profoundly thought provoking book tackles a huge subject: the coming of the nuclear age with bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, and the ways in which it has changed our lives since. Dr Heuser sets these events in their historical context and tackles key issues about the effect of nuclear weapons on modern attitudes to conflict, and on the ethics of warfare. Ducking nothing, she demystifies the subject, seeing `the bomb' not as something unique and paralysing, but as an integral part of the strategic and moral context of our time. For a wide multidisciplinary and general readership.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Bomb by Beatrice Heuser,D.B.G. Heuser in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

A Turning Point of World War II?

To Our good and loyal subjects: After pondering deeply the general trend of the world and the actual conditions obtaining in Our Empire today, We have decided to effect a settlement of the present situation by resorting to an extraordinary measure.We have ordered Our Government to communicate to the Governments of the United States, Great Britain, China and the Soviet Union that Our Empire accepts the provisions of their Joint Declaration [unconditional surrender].… the enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb, the power of which to do damage is indeed incalculable, taking the toll of many innocent lives. Should we continue to fight, it would not only result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but also it would lead to the total extinction of human civilization.1

This was the radio broadcast made by the Japanese Emperor on 15 August 1945, announcing Japan’s surrender. As the end of war in the Far East, this was the end of the Second World War, and certainly a caesura in world history. But was the use of atomic bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki a turning point in the Second World War? Was it essential to bring the war to a close in the Far East? Or might Japan have surrendered soon anyway? This is the first issue we shall examine in this chapter, reflecting the main scholarly debate on the subject. The second will be whether the use of the bomb on Japan was indeed the most defining event of the Second World War and whether it stood out from other events and developments as the worst of its kind.

A turning point in World War II

While a majority of Americans still believe that on balance, dropping the atom bombs was the right decision to take,2 a number of historians have questioned the necessity and morality of this decision. They have conducted very detailed studies of the documentation available that provides clues to the motivations of US President Harry S. Truman and his chief advisers. Until the end of his life, Truman himself repeated over and over that he stood by his decision, as, in his view, it had saved many more lives (mainly of American servicemen) than it cost in numbers of victims. Truman retrospectively claimed to have thought at the time that, because of the determination of the Japanese military not to be taken prisoner and their willingness to incur death rather than surrender, the conquest of Japan on the ground would have resulted in further very high casualties for both sides.3 Among the experts on the subject, historian Herbert Feis has argued that this was indeed the main reason why Truman gave orders to drop the bomb.4

While Truman himself claims never to have lost a night’s sleep over the issue,5 some did, most notably historian Gar Alperovitz, who made the question of the President’s motivation his own main subject of research over decades. Indeed, in 1965, with the Vietnam War fully under way, and its critics ever more interested in the origins of the Cold War which was so hot and deadly in South East Asia, Alperovitz published a historical blockbuster called Atomic Diplomacy: Hiroshima and Potsdam. In this he argued that Truman’s main motivation was not to cut short the war in the Far East, but to impress Stalin with the military power America could command, lest Stalin might hope to take advantage of the inexperienced new US President in the post-World War II peace settlement. The book was grist to the mills of those (mainly Left-wing) critics of the US government who saw the Vietnam War as a further aberration of a continuous US policy which had sought confrontation with the USSR even when both had just emerged as victorious allies from the war against National Socialist Germany. The Cold War ‘revisionists’ thus saw a terrible logical link between the willingness of President Truman to kill one-and-a-half thousand Japanese civilians and his willingness to engage the Soviet Union in a conflictual confrontation, leading to the sacrifice of lives in the Korean War and now in Vietnam. Responsibility for the Cold War was thus assigned to Truman, his advisers and his successors, as much as, if not more than, to the Communist side.

A great debate ensued about every minor aspect of the atomic bomb decision, and the counsellors involved. Had there been serious alternative strategies discussed by the US government in 1945, and would these really have led to even greater casualties? Or was it a ’strange myth’ that ‘Haif a million American lives [were] saved’?6 Had General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Truman’s successor as US President, really (as he later claimed) opposed the decision to use the bomb in 1945?7 Was Truman’s own decision not a bit of both, the hope of saving American GIs’ lives and the hope of impressing Stalin?8 The evidence has been gone through meticulously again and again, and a few hairs seem to have been split in the process.9 In a very large collective research project, Gar Alperovitz reopened the issue and in 1995 published his old and new findings in The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb and the Architecture of an American Myth, and provoked both ardent praise and angry responses, such as that by Robert James Maddox.10 The debate is certainly not concluded. What are the main points raised by the historian-critics of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki decisions?

Let us begin with the development of the war in the Far East. The US Air Force had massively increased its bombing of the Japanese homeland in the winter of 1944–45. In November 1944, suburbs of Tokyo were for the first time subject to significant bombardment. In March 1945 came the great bombing of Tokyo with conventional ordnance which led to a fire-storm costing the lives of at least 88,000 people – a figure, as we shall see, that was comparable to the losses of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Morale was declining rapidly; doubts about Japan’s ability to win the war grew exponentially among the population.

The American conquest of the Pacific island of Iwo Jima in the last week of March allowed the US Air Force to deploy fighter planes there. These could henceforth accompany and protect bombers on their sorties to destroy targets on the Japanese mainland. On 1 April 1945 the Americans landed on Okinawa, which again gave them air bases closer to the Japanese mainland, further facilitating air bombardment of mainland targets.

As early as 6 April 1945 the US State Department received information that, via neutral Sweden, civilian members of the Japanese government had put out feelers to negotiate an armistice. The US minister in Stockholm reported that the Japanese would probably accept far-reaching conditions, but that ‘The Emperor must not be touched. However, the Imperial power could be somewhat democratized as is that of the English [sic] King.’11

It must be noted in this context that Japanese culture inclined towards a deep veneration of the Emperor, even though this was a person whom, prior to the famous broadcast of 15 August 1945, ordinary citizens had never heard speak even on the radio, let alone seen in the flesh. The US Strategic Bombing Survey, for example, which was written up well after Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1946/7, listed four factors as the most important in fuelling the determination of the Japanese to carry on the war, namely,

• Fear of the consequences of defeat

• Faith in the ‘spiritual’ strength and invincibility of the nation

• Obedience to and faith in the Emperor

• The black-out of information about the war.12

When during the survey, Japanese respondents were asked what changes should occur in the future, with the additional question: ‘And what about the Emperor?’, 69 per cent expressed the wish to retain him, 12 per cent would not answer, another 12 per cent said they could not ‘discuss such a high matter’ (both those refusing to answer and those who said they could not discuss this matter may have held the same view, namely that it was unthinkable for them to say anything against the Emperor). Only 3 per cent thought the Japanese should ‘drop him’.13

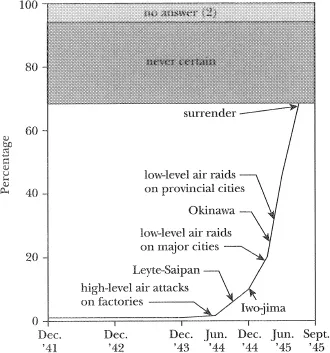

Figure 1.1 The growth of certainty that Japan could not win

Source: The United States Strategic Bombing Survey: The Effects of Strategic Bombing on Japanese Morale (Morale Division, June 1947)

Source: The United States Strategic Bombing Survey: The Effects of Strategic Bombing on Japanese Morale (Morale Division, June 1947)

It is thus crucial in this context that the Japanese were almost more concerned about the fate of their Emperor than about their own fate, and that the Allies did not convey the impression that while the Japanese government was seen as guilty of the war and as meriting punishment, the Emperor, as standing above actual policy-making, might be spared. As we shall see, the issue of the treatment of the Emperor would remain crucial in the following months.

Another key reason for Japanese reluctance to surrender was their fear of maltreatment at the hands of the Americans. The image which the Japanese had of the Americans was that they would show no mercy to the Japanese population, once they occupied Japan. The mass suicides of Japanese Civilians on individual islands conquered by the Americans testify to this. It is interesting to note that the Japanese projected onto their opponents the attitude towards prisoners of war which they themselves showed in their treatment of captured enemies – Japanese cruelty shown in Manchuria, China, the Philippines, Indonesia and South East Asia beats any records bar those set by the extermination camps of the Germans.

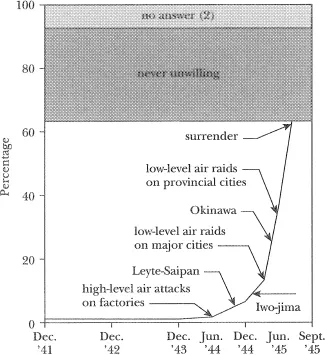

Figure 1.2 The growth of unwillingness to continue the war

Source: The Effects of Strategic Bombing on Japanese Morale

Source: The Effects of Strategic Bombing on Japanese Morale

In mid-May 1945, after the defeat of Germany, further news of Japanese peace feelers – again ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. A Turning Point of World War II?

- 2. A Turning Point in Strategy?

- 3. A Turning Point in the Development of ‘Total War’?

- 4. A Turning Point in the Thinking about the Morality Of War?

- 5. A Turning Point in the History of Warfare and Inter-societal Relations?

- Useful Further Reading

- Index