![]()

Section II

The five future governance roles

![]()

3

The directors’ role in stopping the rot

The argument for effective corporate governance values as the basis for national leadership and governance

The current Western fashion for denigrating directors of all types is emotionally understandable following the financial crisis of 2008. However, it demeans the many directors who are still determined to develop their people and organizations, but often without sufficient ideas, models or vocabulary to deal with the deep governance issues that beset our society. This chapter is a personal attempt to ease this unhealthy situation. It forms a fifth of my proposed design for a national corporate governance learning system.

People are comfortable if they feel well led. This allows them to get on with their lives while retaining the security of having the democratic right to eject the rascals if the quality of their governance fails. In the UK, we have two millennia of models of effective national leaders from Boudicca, Alfred, Elizabeth I, Cromwell, Nelson, Wellington, Churchill, Elizabeth II, to Margaret Thatcher. All have passed the key test of any leader: that the majority, with the often grudging acceptance of the minority, are willing to follow them to achieve a greater cause. Each had very different personalities and, at a time of national emergency, had a passionate belief in what was right for their country. None of these leaders was universally popular, and not all of them were loved. But all were effective in their own way.

The problem with many of our current leaders of national institutions such as Parliament, international business, local government, the National Health Service, the BBC, the universities, schools, the police, the trades unions, media, sport and our charities (and this is only a partial list) is that they appear disappointingly purposeless and colourless personalities. Opinion polls show frequently that the public no longer see our leaders as effective. Their deficiencies are magnified by real-time criticism, disseminated over the internet and the wider media, and so any credibility is continually eroded. This process is nationally debilitating because the public have not yet learned to ask discerning questions of their leaders’ competence. The public needs agreement on what is effective political and organizational governance and leadership, especially between the legislative, directoral and the executive functions. Paradoxically, despite the criticisms, we have already invested in and built the legal infrastructure, so I argue that we can benefit much by accepting what has been learned about effective corporate governance already, and then using that as the default position from which to disseminate widely a system for the necessary direction-giving to cope with our turbulent future. And I do stress the importance of creating a system of continuous learning to achieve this aim.

I am not advocating the creation and development of a cadre of national super-leaders of the “dominator” stereotype.100 Despite Donald Trump, the “leader as action hero” single stereotype is of limited use in stakeholder-based, inclusive organizations. Alternatively, I advocate that the conscious national development of the concept of a range of effective leaders is accepted by the public as a key to their sustainable health and wealth. This depends on the development of learnable, agreed, assessable competences, linked to a set of values and behaviours for leaders of any organization: public, private or not-for-profit. As the UK and South Africa currently have the world’s most developed systems of effective corporate governance, we should use these countries as the benchmark from which we can then develop our future organizations internationally. This builds on my suggestion in Chapter 2 that we treat the practice of effective direction-giving as a profession, that we regularly assess practitioners’ competence, and have sanctions for professional malpractice.

The current muddle over the title of “director”

But first we need to clarify the much-abused term “director”. I have mentioned that the use of the title “director” is unlawful in most Commonwealth countries, unless you have personally registered your title at Companies House or the national equivalent. Yet the title is constantly overused, usually unlawfully. The term is distributed like confetti in good times, when there is a need to retain senior staff, and in bad times when remuneration cannot be increased so other forms of compensation are deemed necessary. This demeans the title, exposes those folk not registered to the legal risk of unlimited personal liability, and it causes great confusion in the public’s mind as to who is a “director” and whether the title has any validity. In that growing basket case of corporate governance known as the USA, the term “director” is doubly confusing because it is used to describe both members of the board of directors and to the position directly below a vice president.

Matters are made worse internationally by the consciously lax use of the term “director” in organizations. Existing boards and HR departments often offer the job title “director” to employees as if it were a compensation prize, especially if larger financial rewards are not on offer. This is particularly true within financial institutions. If the exposure of a director’s personal wealth to unlimited liability is not made clear when a non-registered director title is offered, then this exposes a business’s key employee to high and unnecessary risks. They become what I call “accidental directors”. This is equally true if people are offered such job titles as “Director of …”. Strong case law also exists which shows that people “holding themselves out to be” or “purporting to be” a director, will be treated by the courts as if they were. Such people are then accredited with the same responsibilities and liabilities as a lawfully registered director, but without access to any insurance cover. Few people in this position seem to know that they are exposed to unlimited personal liability. They only start to care when indicted, by which time it is already too late to cover themselves.

Internationally, regulators have allowed this sloppy use of the “director” title to become the norm. In the UK and most of the 54 Commonwealth countries, you are either a registered “director” or you are not, from the legal viewpoint. However, the regulators have let the terms “executive director” and “non-executive director” become the norm in many countries. Yet, legally speaking, neither term exists. This was administratively convenient at the time of the Cadbury Report and has just been copied by other regulators without care. What is worse is that the financial services’ lack of understanding of, and contempt for, this basic legal point means that they, together with the financial regulators and politicians, have not only continued this bad practice but now compounded their folly by creating yet another class of directors – approved and non-approved – without squaring this with the Companies Act 2006.

The foolishness of “the senior management regime” in the UK

In a desperate and rushed effort by politicians and bureaucrats to save the reputation of banking and the wider financial services of the City of London, the regulators, together with the Financial Conduct Authority, the Bank of England and the Prudent Regulation Authority, have created the fearsome “senior management regime”. This is a triumph of arrogance over, and dismissal of, the hard-won general duties of directors. Directors should carefully note the title. All three words are incorrect. It is not a “senior management” position as the drafters have not appreciated the basic legal differentiation between directors and managers, and instead have attempted to tar all with the same brush. Their intention is worthy – to ensure that all “senior managers” accept personal responsibility for their actions and any risks taken, a laudable aim in that it brings the actions of the top executives under legal scrutiny. It is very odd that they were not before. They now have a statutory duty to take reasonable steps to prevent regulatory breaches in their specified area of responsibility.

Early experience shows that this has caused fragmentation of board and senior management’s collective responsibility, as each individual now seeks to ensure that they cannot be held personally responsible. This is against the essence of the General Duties of the Companies Act 2006. These values of domination by the regulator are reflected in the “regime” title. It suggests little discretionary ability under the UK’s long-established value of principles-based governance. This is not cooperative language. If anything, it suggests that the politicians are seeking revenge on the banking sector in two ways: first, by encouraging the regulators to abandon the basis of the Companies Act; second, by being so strict in their desire to impose some form of qualification on banking directors that they are now screening out suitably diverse people for directorships who could guarantee the “independence of thought” and ensure the “care, skill and diligence” demanded of banking directors under the Companies Act. Their panic is consciously reducing the gene pool from which effective future banking directors can come. This is a classic short-term fix that will create unhealthy long-term problems. They have created four different categories of directors on banking boards none of which are in the Companies Act: “non-executive directors”, “executive directors”, “approved directors” and “non-approved directors”. These strange combinations are guaranteed to create confusion and division around what is meant to be a “unitary” board. As Henry IV says, “uneasy lies the head that wears the crown”.101 This is not conducive to effective governance.

The confusing words used to describe directors

In an attempt to demonstrate how confusing such titles can be, I have drawn up a list of the more common current “director” titles in general circulation:

- Registered or statutory director (the default position)

- “Accidental” director (the most common category – they are unaware that they are legally acting as directors and have not registered, nor are they aware of their exposure)

- Non-executive directors (a nonsense title as they may be part-time but have the same statutory duties as all directors)

- Executive directors (another nonsense title: most executive directors don’t realize that they need two different employment contracts, one as a director and one as an executive employee)

- Shadow directors (who influence events from behind the scenes; they, too, rarely realize that they have the same duties and liabilities as a registered director but usually without liability insurance)

- “Representative” directors (who are unlawful; see below)

- The chairman of the board of directors (which is correct; but note that they are not the chairmen of their companies but only of the board)

- The managing director (but not the chief executive officer, unless they are also registered as a director of the company)

And that is before we get into the fashionable US title nonsense.

So let us go back to the basics of corporate governance.

What is corporate governance? The “director’s dilemma”

As I have already written much in this area,102 I have chosen to explore here only the key issues relating to the present rot.

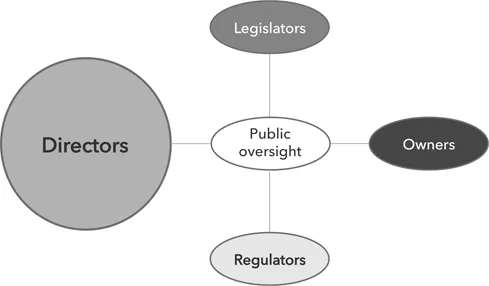

Based on those basic governance values of accountability, probity and transparency, “corporate governance” seeks to solve a fundamental problem for anyone charged with giving direction to an organization: how can we drive our organization forward, while keeping it under prudent control – otherwise known as the “director’s dilemma”? Directors are legally responsible for both, simultaneously. The “drive forward” aspect of the dilemma is to “ensure the success of the company”, according to company law, while also ensuring that the company and its executives are “under prudent oversight of their actions”. This is the complex, continuous and difficult intellectual challenge for every board. Yet most boards focus only on the prudent control aspects as they tend to be populated by executives who will know a lot more about this. “The future” is seen as too difficult. It is full of uncertainty and risk which, being executives, they are still keen to avoid.

In the UK, the Commonwealth and the European Union, I advocate that the director’s dilemma should be applicable to all nationally registered organizations – including state-owned enterprises, trades unions, partnerships, local governments and not-for-profit organizations. In stopping the rot, we are all seeking to invest heavily in creating and regulating effective corporate governance, so why restrict it only to the directors of listed companies? Surely our nations would derive increased social and financial wealth from such a comprehensive approach? The competent delivery of effective corporate governance demands the continuing resolution of the director’s dilemma. The competence of our national organizations’ leaders and governors should be regularly tested against this.

Defining direction-giving

The modern, global corporate governance movement derives from the intellect and energies of the Quaker and human-values-driven Sir Adrian Cadbury, who died in 2015. The publication of his The Financial Aspects of Corporate Governance,103 commissioned by the then International Stock Exchange, London, and the Institute of Chartered Accountants of England and Wales, shocked most directors and politicians. They suddenly realized that directing was a proper job, a crucial role and not just a (honorary?) title. Unfortunately, the backing by such heavy financial services groupings has created two myths. The first is that the report only applies to listed companies and their financial business values. Paradoxically, the second myth is that the report is complete in itself and not a work in progress. It is seen by many politicians internationally as a fixed template for all organizations. Many have subsequently tried to apply it regardless of whether or not it fits. The report was a belated response to Lord Halifax’s comment that “the trouble with British companies is that they mark their own examination papers”.104 It undoubtedly raised the profile of “corporate governance” internationally and introduced it to many. But now, despite its “comply or explain” ethos, it is becoming mired in ever more regulatory processes that add little. For over 20 years I worked with and was in correspondence with Sir Adrian. Just before he died, and in relation to this book, he insisted that I must do all I can to get the focus of corporate governance back to the primacy of ensuring the success of the business. He was increasingly concerned about the growing fixation with the primacy of compliance.

Feedback for the board

The second derivation of kubernetes (the origin of the word “governance”) (see page 4) – “cybernetics” – is highly topical today and yet unknown by many directors, politicians and the public. Its meaning comes from sense of kubernetes relating to the feedback control and learning systems of a direction-giving mechanism. It seems that this second meaning has skipped a couple of millennia, but it resurfaced after World War II in the work of Norbert Weiner,105 Reg Revans,106 Stafford Beer107 and W.R. Ashby108 as the “systems thinking”, “feedback loops”, “requisite variety (diversity)” and “action learning” concepts that emerged to drive our organizational development thinking forward. Boards are becoming more comfortable using these sustainable learning systems, especially in the “age of uncertainty”. Politicians, directors, regulators and owners: please take note.

Directing not managing

To go deeper into the current corporate governance debate we need to review a very common public misperception. Most people assume that the words “managing” and “directing” are synonymous. They are not. They are abused continually by the media, managers, politicians, owners, regulators and by directors themselves. This does not make such abuse right. Legally, registered directors are jointly and personally liable for the total performance of their organization, not managers, nor politicians. “Directors” are personally bound by a tough set of laws, usually the Companies Act or ordinances of their country. Their personal wealth can be at risk if they take unlaw...