- 374 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Britain in the World Economy since 1880

About this book

Bernard Alford reviews the changing role, and diminishing influence, of Britain within the international economy across the century that saw the apogee and loss of Britain's empire, and her transformation from globe-straddling superpower to off-shore and indecisive member of the European Community. He explores the relationship between empire and economy; looks at economic performance against economic policy; and compares Britain - through and beyond the Thatcher years - with her European partners, America and Japan. In assessing whether Britain's economic decline has been absolute or merely relative, he also illuminates the broader history of the world economy itself.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Britain in the World Economy since 1880 by Bernard W.E. Alford in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Storia & Storia britannica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

StoriaSubtopic

Storia britannicaChapter One

The Challenge to Late Victorian Apogee

Economy and Society

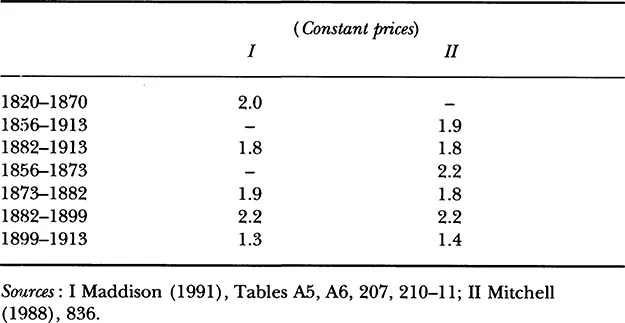

The economic ascendancy that Britain had achieved over the world economy by 1880 was the outcome of a cumulative process extending over the previous two centuries. At its core were the dynamics of industrialization. To what extent this growth stemmed from revolutionary changes in economic development in the mid-eighteenth century or from evolutionary changes extending over a longer period is still a matter of dispute.1 But it is clear that during the nineteenth century growth rates were low by modern standards. Britain can be characterized as a two per cent economy. More detailed figures are provided in Table 1.1. Translated into GDP per worker the rate fluctuated around 1 per cent per year.

1. For a useful survey of the debate on the industrial revolution see P. Hudson, The Industrial Revolution (1992). See also J. Hoppitt, ‘Counting the Industrial Revolution’, Economic History Review, 43 (1990), pp. 173—93; J. Mokyr, ‘The Industrial Revolution and the New Economic History’, in Mokyr (ed.), The Economics of the Industrial Revolution (1985). In many respects the best analysis remains D. C. Coleman, ‘Industrial Growth and Industrial Revolutions’, Economica, 89 (1956), pp. 1–22.

For all their apparent precision these statistics provide no more than crude orders of magnitude because of the far from perfect data from which they have been constructed. The main features of economic growth are reasonably clear, however. Not only was it moderate, it was fairly evenly distributed over all sectors of the economy and, it should be noted, services maintained its important role, albeit in changing form. Coke town and Mr. Gradgrind, brought to public consciousness by Dickens, by no means wholly typified the economy at any stage in the nineteenth century. The worlds of Middlemarch and Cranford were equally the reality. Some indication of the nature of economic society is given by the fact that the 1871 census was the first to register a decline in the agricultural workforce. But with a labour force of 3 million, agriculture still remained the single largest occupation and it accounted for 22 per cent of the working population. Equally significant was the continued rise in the number employed in domestic service. At 1.85 million it amounted to 12.3 per cent of the workforce in 1881. But industrialization and industrialism were the new forces with which the old order had to come to terms.2

2. Although superseded in some respects, H. M. Lynd, England, in the Eighteen Eighties (Oxford, 1945) still offers an outstanding interpretation of the period.

Table 1.1 United Kingdom: average annual rates of growth of GDP, 1820–1913

Britain’s leading world position in 1880 was universally recognized though it was not conceived of in the kind of quantitative measures which are nowadays an essential part of the vernacular of political economy. In economic matters, as in much else, the Victorians thought in terms of progress and expansion. Economic growth did not have the meaning now attached to it, but steady growth was, in effect, fully in accord with Victorian values. In common form these values were popularized by Samuel Smiles in his best-selling book Thrift, which extolled the virtue of regular saving and the power of compound interest.3 This rhythm of economic progress was in harmony with the expansion of the Empire. British imperialism was a process of accumulation. It is true that imperial rivalry among the Great Powers at the end of the century became a vigorous affair, and that between 1870 and 1914 the British Empire increased in area by nearly two and a half times, but in economic terms this was expansion at the margin since the old territories remained dominant in imperial trade and finance. And the new acquisitions owed much to the simple extension and consolidation of existing territorial advantage and to the habitual exercise of diplomatic skills.4

3. A. Briggs, Victorian People (1955), Chapter 5.

4. There is a huge literature but useful surveys are P. J. Cain, Economic Foundations of British Imperialism (1980); P. J. Cain and A. G. Hopkins, British Imperialism: Innovation and Expansion 1688–1914 (1993); D. K. Fieldhouse, Economics and Empire, 1880–1914 (1973); R. Owen and B. Sutcliffe (eds), Studies in the Theory of Imperialism (1972); B. Porter, The Lion’s Share, A Short History of British Imperialism (1975).

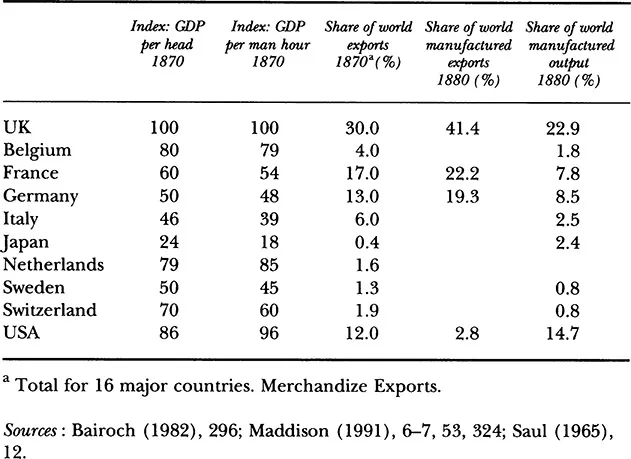

Table 1.2 Indicators of Britain’s position in the world economy, c.1870/80

Victorians and Victorian values are, nevertheless, concepts easily open to historical misrepresentation. They can be used to convey a sense of coherence and consistency that is alien to reality. The society of the time has been aptly described as ‘ramshackle and amorphous’ because of the continuous cross currents of change and conflict within it.5 A Victorian, so defined, did not become overnight the quite different person of an Edwardian simply because one monarch succeeded another. Such a transformation would truly reflect a monarchy of awesome power. And the society of which these individuals were a part is difficult to define because its boundaries were fluid. These boundaries could extend beyond the frontiers of the nation state to incorporate, for example, imperial links or foreign ethnic ties. There are, in other words, various levels at which society may be perceived, each layer involving sets of relationships in turn interlinked with other layers.6

5. losé Harris, Private Lives, Public Spirit: A Social History of Britain, 1870–1914 (1993), p. 8.

6. A study of particular aspects of this general issue is provided by D. Feldman, Englishmen and Jews: Social Relations and Political Culture, 1840–1914 (1994).

The analysis of political, and more particularly in this context, economic power, is similarly vulnerable to undue historical simplification. For example, Marx, an eminent Victorian no less, reduced the complexities of social relationships to subservience to the dominant and unifying power of capitalist exploitation. Whilst Marxian analysis finds little favour among historians nowadays, the idea within it of the power of an elite group to manipulate the economy to its own ends still holds strong appeal. The most important recent version takes the historical form of so-called gentlemanly capitalism.7 This creature will be examined in more detail later (Chapter 3) but in essence it embodied ‘a complex of economic, social and political influences’ centred on the City of London, of such power that it controlled much of the economic life of the nation and directed it to its own ends. One of the problems with such historical characterizations is that, even when economic power can be identified and its exercise documented, the outcome is not a foregone conclusion. Historical actors, no less than those of the present day, operated within a world of imperfect knowledge in which the outcome of their actions was frequently unintended and consequently not in their self-interest.

7. Cain and Hopkins, British Imperialism.

The economic divisions in society in the late nineteenth century were thus complex and changing. What might appear to be precise definitions of occupations in census returns cover wide variations in practice, and these variations increased over time. Whilst it is essential to recognize this fact it is, however, impossible and unnecessary in this context to provide a comprehensive analysis of late Victorian society. For present purposes, a broad brush will be applied to paint contrasts between the gainers and losers from late-nineteenth-century British prosperity.

During the latter half of the Victorian period prosperity spread to the mass of the people and covered a rise in population from 23 million in 1861 to 30 million by 1881. Whilst the richest 4 per cent of income receivers swallowed up nearly half the total income in 1880, absolute real incomes had risen for nearly all.8 Between 1861 and 1881 average real wages rose by 37 per cent. In large part this was the result of Britain’s ability to reap the comparative advantage of exporting manufactured goods and financial and commercial services in return for imports of increasingly cheap grain from North and South America, in particular. Over the 1880s real wages rose by a further 19 per cent.9 And to the flow of cheap foreign grain was added a growing amount of chilled meat from the southern hemisphere transported in the new technology of refrigerated ships. Even among wage-earners, however, these gains were not distributed evenly. There were significant occupational and regional differences; moreover, the available statistics probably overstate the gains since they do not adequately take account of the ‘reserve army’ of the underemployed and those in low-paid service occupations. At the extreme, income per head in London was between two and four times the level in Wales. Nevertheless, the gains for all regions were substantial.10

8. A. L. Bowley, The Change in the Distribution of National Income, 1880–1913 (Oxford, 1920), p. 16.

9. B. R. Mitchell, British Historical Statistics (Cambridge, 1988), pp. 149–50. See also C. Feinstein, ‘What Really Happened to Real Wages? Trends in wages, prices, and productivity in the United Kingdom, 1880–1913’, Economic History Review, 43 (1990), pp. 329–55 and idem., ‘New Estimates of Average Earnings in the United Kingdom, 1880–1913’, Economic History Review, loc. ät., pp. 595–632.

10. C. H. Lee, The British Economy since 1700: A Macroeconomic Perspective (Cambridge, 1986), p. 131. E. H. Hunt, ‘Industrialization and Regional Inequality: Wages in Britain’, Journal of Economic History, 46 (1986), pp. 935–66.

The working class contained many elements. There was obviously a broad distinction between urban and rural workers. But within each of these categories the divisions were multifarious. The elite was made up of artisans: those who practised a particular manual skill. In terms of income they sometimes ranked higher than those immediately above them in the social scale, and they created their own distinctive culture which, by the 1880s, contained many elements of aspiration to middle-class status. Their major concern was to maintain their position within a plentifully supplied labour market and the obvious way in which to do this was through exclusive craft unions that placed great emphasis on forms of apprenticeship, demarcation rules and wage differentials. These practices were reinforced by a commitment to self-help, self-improvement and, above all, to self-esteem. Welfare schemes, social clubs and intermarriage were important means through which this artisan culture was expressed and sustained.11 Those unable to defend themselves in this way were the unskilled and, to a lesser extent, the semi-skilled.

11. See G. Crossick, An Artisan Elite in Victorian Society. Kentish London 1840–1880 (1978); and C. More, Skill and the English Working Class (1980). For a good survey o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- List of Abbreviations

- Preface

- Dedication

- Introduction

- 1. The Challenge to Late Victorian Apogee

- 2. British Industry and World Trade, 1880–1914

- 3. Finance and Empire, 1880–1914

- 4. The First World War and the Return to Gold

- 5. Britain and the World Depression

- 6. Britain, Europe and the New Postwar World Economic Order

- 7. Comparative Performance and Competitiveness, 1945–61

- 8. Britain and the Climax of the Long Boom

- 9. International Crisis, the EEC and the North Sea El Dorado

- 10. Britain in the World Economy: Falling Behind and Catching Up?

- Appendix: Statistical Sources

- Index