![]()

1

Introduction

What is Human Ecology?

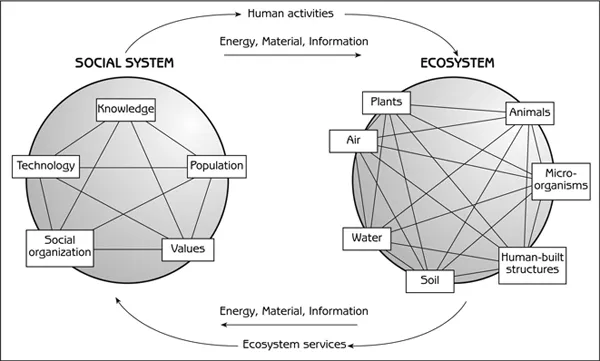

Ecology is the science of relationships between living organisms and their environment. Human ecology is about relationships between people and their environment. In human ecology the environment is perceived as an ecosystem (see Figure 1.1). An ecosystem is everything in a specified area – the air, soil, water, living organisms and physical structures, including everything built by humans. The living parts of an ecosystem – microorganisms, plants and animals (including humans) – are its biological community.

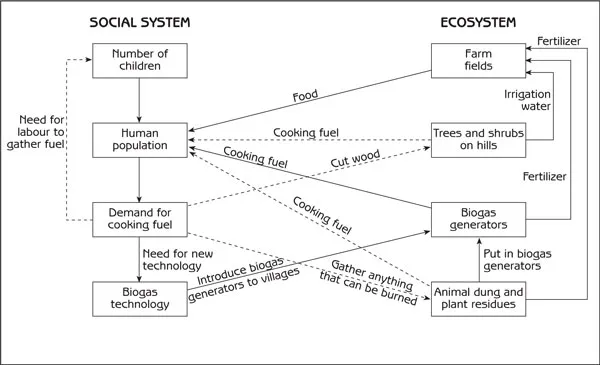

Figure 1.1 Interaction of the human social system with the ecosystem

Ecosystems can be any size. A small pond in a forest is an ecosystem, and the entire forest is an ecosystem. A single farm is an ecosystem, and a rural landscape is an ecosystem. Villages, towns and large cities are ecosystems. A region of thousands of square kilometres is an ecosystem, and the planet Earth is an ecosystem.

Although humans are part of the ecosystem, it is useful to think of human–environment interaction as interaction between the human social system and the rest of the ecosystem (see Figure 1.1). The social system is everything about people, their population and the psychology and social organization that shape their behaviour. The social system is a central concept in human ecology because human activities that impact on ecosystems are strongly influenced by the society in which people live. Values and knowledge – which together form our worldview as individuals and as a society – shape the way that we process and interpret information and translate it into action. Technology defines our repertoire of possible actions. Social organization, and the social institutions that specify socially acceptable behaviour, shape the possibilities into what we actually do. Like ecosystems, social systems can be on any scale – from a family to the entire human population of the planet.

The ecosystem provides services to the social system by moving materials, energy and information to the social system to meet people’s needs. These ecosystem services include water, fuel, food, materials for clothing, construction materials and recreation. Movements of materials are obvious; energy and information are less so. Every material object contains energy, most conspicuous in foods and fuels, and every object contains information in the way it is structured or organized. Information can move from ecosystems to social systems independent of materials. A hunter’s discovery of his prey, a farmer’s observation of his field, a city dweller’s assessment of traffic when crossing the street, and a refreshing walk in the woods are all transfers of information from ecosystem to social system.

Material, energy and information move from social system to ecosystem as a consequence of human activities that impact the ecosystem:

- People affect ecosystems when they use resources such as water, fish, timber and livestock grazing land.

- After using materials from ecosystems, people return the materials to ecosystems as waste.

- People intentionally modify or reorganize existing ecosystems, or create new ones, to better serve their needs.

With machines or human labour, people use energy to modify or create ecosystems by moving materials within them or between them. They transfer information from social system to ecosystem whenever they modify, reorganize, or create an ecosystem. The crop that a farmer plants, the spacing of plants in the field, alteration of the field’s biological community by weeding, and modification of soil chemistry with fertilizer applications are not only material transfers but also information transfers as the farmer restructures the organization of his farm ecosystem.

An example of Social System–Ecosystem Interaction: Destruction of Marine Animals by Commercial Fishing

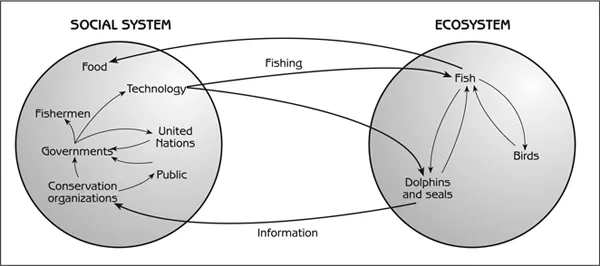

Human ecology analyses the consequences of human activities as a chain of effects through the ecosystem and human social system. The following story is about fishing. Fishing is directed toward one part of the marine ecosystem, namely fish, but fishing has unintended effects on other parts of the ecosystem. Those effects set in motion a series of additional effects that go back and forth between ecosystem and social system (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Chain of effects through ecosystem and social system (commercial fishing in the ocean)

Drift nets are nylon nets that are invisible in the water. Fish become tangled in drift nets when they try to swim through them. During the 1980s, fishermen used thousands of kilometres of drift nets to catch fish in oceans around the world. In the mid 1980s, it was discovered that drift nets were killing large numbers of dolphins, seals, turtles and other marine animals that drowned after becoming entangled in the nets – a transfer of information from ecosystem to social system, as depicted in Figure 1.2.

When conservation organizations realized what the nets were doing to marine animals, they campaigned against drift nets, mobilizing public opinion to pressure governments to make their fishermen stop using the nets. The governments of some nations did not respond, but other nations took the problem to the United Nations, which passed a resolution that all nations should stop using drift nets. At first, many fishermen did not want to stop using drift nets, but their governments forced them to change. Within a few years the fishermen switched from drift nets to long lines and other fishing methods. Long lines, which feature baited hooks hanging from a main line often kilometres in length, have been a common method of fishing for many years. The long lines that fishermen now use put a total of several hundred million hooks in the oceans around the world.

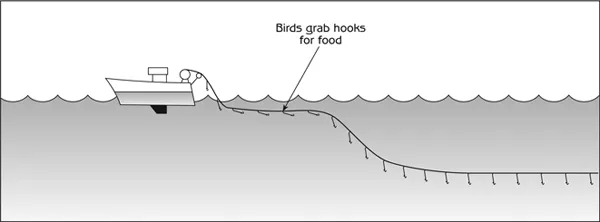

The drift net story shows how human activities can generate a chain of effects that passes back and forth between social system and ecosystem. Fishing affected the ecosystem (by killing dolphins and seals), which in turn led to a change in the social system (fishing technology). And the story continues today. About six years ago it was discovered that long lines are killing large numbers of sea birds, most notably albatross, when the lines are put into the water from fishing boats. Immediately after the hooks are reeled from the back of a boat into the water, birds fly down to eat the bait on hooks floating behind the boat near the surface of the water (see Figure 1.3). The birds are caught on the hooks, dragged down into the water and drown. Because some species of birds could be driven to local extinction if the killing is not stopped, governments and fishermen are investigating modifications to long lines that will protect the birds. Some fishermen are using a cover at the back of their boat to prevent birds from reaching the hooks, and others are adding weights to the hooks to sink them beyond the reach of birds before the birds can get to them. It has also been discovered that birds do not go after bait that is dyed blue.

Figure 1.3 Long line fishing

This story will continue for many years as new effects go back and forth between the ecosystem and social system. Another part of the story concerns seals and other fish-eating animals that may be declining to extinction in some areas because heavy fishing has reduced their food supply. The effects can reverberate in numerous directions through the marine ecosystem. It appears that the decline of seals in Alaskan coastal waters is responsible for the disappearance of impressive kelp forests in that region. Killer whales that previously preyed on seals have adapted to the decline in seals by switching to sea otters, thereby reducing the sea otter population. Sea urchins are the principal food of sea otters, and sea urchins eat kelp. The decline in sea otters has caused sea urchins to increase in abundance, and the urchins have decimated kelp forests that provide a unique habitat for hundreds of species of marine animals. (Another episode in the story of commercial fishing and marine animals is presented at the end of Chapter 11.)

Cooking Fuel and Deforestation in India

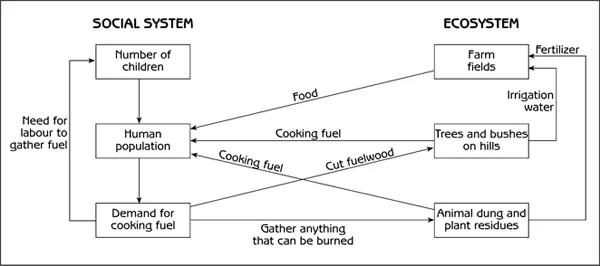

The problem of deforestation in India provides another example of human activities that generate a chain of effects back and forth through the ecosystem and social system. The following story shows how a new technology (biogas generators) can help to solve an environmental problem.

For thousands of years people in India have cut branches from trees and bushes to provide fuel for cooking their food. This was not a problem as long as there were not too many people; but the situation has changed with the radical increase in India’s population during the past 50 years (see Figure 1.4). Many forests have disappeared in recent years because people have cut so many trees and bushes for cooking fuel. Now there are not enough trees and bushes to provide all the fuel that people need. People have responded to this ‘energy crisis’ by having their children search for anything that can be burned, such as twigs, crop residues (bits of plants left in farm fields after the harvest) and cow dung. Fuel collection makes children even more valuable to their families, so parents have more children. The resulting increase in population leads to more demand for fuel.

Figure 1.4 Deforestation and cooking fuel (chain of effects through ecosystem and social system)

Intensive collection of cooking fuel has a number of serious effects in the ecosystem. Using cow dung as fuel reduces the quantity of dung available for use as manure on farm fields, and food production declines. In addition, the flow of water from the hills to irrigate farm fields during the dry season is less when the hills are no longer forested. And the quality of the water is worse because deforested hills no longer have trees to protect the ground from heavy rain, so soil erosion is greater, and the irrigation water contains large quantities of mud that settles in irrigation canals and clogs the canals. This decline in the quantity and quality of irrigation water reduces food production even further. The result is poor nutrition and health for people.

This chain of effects involving human population growth, deforestation, fuel shortage and lower food production is a vicious cycle that is difficult to escape. However, biogas generators are a new technology that can help to improve the situation. A biogas generator is a large tank in which people place human waste, animal dung and plant residues to rot. The rotting process creates a large quantity of methane gas, which can be used as fuel to cook food. When the rotting is finished, the plant and animal wastes in the tank can be removed and put on farm fields as fertilizer.

If the Indian government introduces biogas generators to farm villages, people will have methane gas for cooking, so they no longer need to collect wood (see Figure 1.5). The forests can grow back to provide an abundance of clean water for irrigation. After being used in biogas generators, plant and animal wastes can be used to fertilize the fields, food production will increase, people will be better nourished and healthier, and they will not need a large number of children to gather scarce cooking fuel.

Note: Dashed arrows show effects that are drastically reduced by the introduction of biogas generators.

Figure 1.5 Chain of effects through social system and ecosystem when biofuel generators are introduced to villages

However, the way that biogas generators are introduced to villages can determine whether this new technology will actually provide the expected ecological and social benefits. Most Indian villages have a few wealthy farmers who own most of the land. The rest of the people are poor farmers who own very little, if any, land. If people must pay a high price for biogas generators, only wealthy families can afford to buy them. Poor people, who do not have biogas generators, will earn money by gathering cow dung to sell to wealthy people for their biogas generators. Poor people may not care much about the ecological benefits from biogas generators because a better supply of irrigation water offers the greatest benefits to wealthy farmers who have more land.

As a consequence, the benefits from biogas generators could go mainly to the wealthy, widening the gap between the wealthy and the poor. Poor farmers, who see few benefits for themselves, might continue to destroy the forests, and the community as a whole might receive little benefit from the new technology. To improve the situation, it is important to make sure that everyone can obtain a biogas generator. Then everyone will enjoy the benefits, and the vicious cycle of fuel scarcity and deforestation will be broken.

Sustainable Development

Unintended consequences such as the ones in the story abou...