![]()

Softwoods and hardwoods

Timber defects

INTRODUCTION

Woodworkers do not need a degree in wood science or biology, but they do need a certain basic knowledge regarding the converted (sawn) timber from different commercial species of felled trees, its often unruly behaviour and defects and its suitability or not for certain jobs. Such basic botanical knowledge – aimed at briefly here – is an essential foundation upon which to develop an understanding of working with this fascinating and rewarding material.

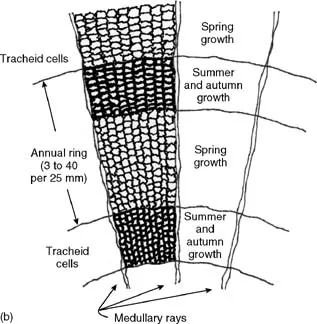

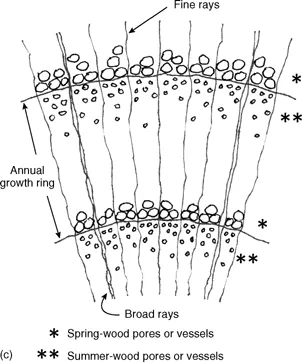

GROWTH AND STRUCTURE

Trees are comprised of a complex structure of microscopic cells which take up sap (moisture containing mineral salts) from the soil via the roots, through the sapwood to the branches and the leaves, where it is converted into food and fed back to the new, inner bark (or bast) in the cambium layer. The cambium layer conveys the food to the growing parts of the tree via the medullary rays. Another group of cells, which form the bulk of the hardwoods' structure, are the fibres. These provide mechanical strength to the structure of the tree. Botanically, the tubular cells of softwood are called tracheids and the cells of hardwood are called vessels or pores.

CLASSIFICATION

Trees are classified botanically, using two-worded Latin names such as Araucaria angustifolia (Parana pine), Quercus robur (English oak), etc; and they are also classified commercially into softwoods and hardwoods. However, these universally accepted trade names must not be taken too literally, as some softwoods are hard and some hardwoods are soft. Parana pine, for example, is botanically a softwood which is quite hard – and Obeche (Triplochiton scleroxylon), a hardwood, is quite soft. The names really refer to the different growth and structure of the trees and their use in a commercial sense.

Softwood

Softwood refers to timber from coniferous trees – cone-bearing trees with needle-shaped leaves – which are mostly evergreens and are classified as gymnosperms. These include the pines and firs, etc. Such species are used extensively for joinery and carpentry work and are marketed as being either unsorted or graded according to the straightness-of- grain and the extent of natural defects (described later).

Redwood and whitewood

Softwood is also described as being either redwood or whitewood. Redwood refers to good quality softwood such as Scots pine, Douglas fir, red Baltic pine, etc, which has very close, easily discernable annual rings denoting slow, structural growth (a necessary ingredient for strength), a healthy golden-yellow or pinkish-yellow colour and a good weight – and whitewood usually refers to a poorer quality of softwood such as a low grade of European spruce (picea abies from the pinaceoe family), which has very wide (barely discernable) annual rings denoting fast growth and a lack of the required thick-walled, strength-giving cells (tracheids), a pallid, creamy-white colour and an undesirable light weight. It usually has hard glass-like knots – which splinter and break up easily when planed or sawn – and it is not very durable.

Hardwood

Hardwood refers to timber mostly from deciduous trees that have broad leaves which they shed in autumn. These are classified as angiosperms and include afrormosia, iroko, English oak, the oaks from other countries, mahoganies, beeches, birches, etc. The first three of these named hardwoods are very strong and durable and are often used in the manufacture of external joinery such as doors, door- and window-sills, door-and window-frames, etc. Of course, for aesthetic reasons, hardwoods from a wide variety of species are also used for internal joinery.

BOTANIC TERMINOLOGY

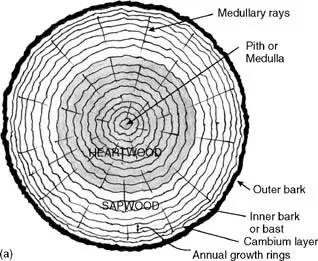

Medullary rays

Figure 1.1(a)(b)(c): This term refers to thin bands of cellular tissue, also called parenchyma or pith rays, which serve as storage for food which is passed through ray pits to the tracheids for distribution. These rays radiate from the pith in the centre of the tree, to the bark. The rays become very decorative when exposed superficially in certain timbers such as quarter-sawn oak, producing an effect known as silver grain.

Sapwood

Figure 1.1(a): This is the youngest, active growth of a tree, occupying a narrow or wide band, varying from about 12mm width in some trees, up to half the radial area of the tree's trunk, adjacent to the heartwood which occupies the central area. It can often be detected on the surface-edges of slab-sawn boards as a light blue to greyish blue in softwoods – and in hardwoods, the colour of the sapwood is usually lighter than the heartwood. Because of the sapwood's open grain and its large amount of sap and mineral content, it has a lower durability than heartwood and is therefore less stable. However, it is still used, but because it is more absorbent than heartwood, its position on external joinery components – such as sills – should (ideally) be on the internal part of the sill.

Figure 1.1 (a) A cross-section through a tree trunk showing a typical area of heartwood and sapwood; annual growth rings; the pith or medulla; the radial medullary rays; the outer bark; the inner bark, bast or phloem; and the cambium layer.

Heartwood

Figure 1.1(a): This is the mature central portion of a tree, which – because of the effect of the stabilized content of substances such as gum, resin and tannin – is usually darker than the sapwood. Each year a band of sapwood becomes a band of heartwood, as a new band of sapwood is added from the cambium layer around the tree trunk.

Cambium and annual rings

Figure 1.1(a)(b)(c): Each year a layer of new wood is formed around the outer surface of the tree, varying in thickness from 0.5mm to 9mm for different species. This growth forms under the bark in the cambium layer and – as mentioned above – this cambium layer becomes an annual ring as it is superseded by a new cambium layer.

Figure 1.1 (b) Artistic impression of the magnified cellular structure of softwood.

Figure 1.1 (c) Artistic impression of the magnified cellular structure of hardwood.

Spring and summer growth of annual rings

Figures 1.1(b)(c): Most annual rings show themselves distinctly on the end-grain of converted (sawn) timber and this is because the spring growth of the rings is lighter in appearance (because the cells are larger) and this contrasts (usually distinctly) with the summer and autumn growth of the rings which are darker in appearance (because the cells are smaller and denser).

SEASONING

Seasoning of timber after it is felled and converted (sawn into a variety of sectional sizes), means drying out and reducing the moisture and sap until a certain, necessary percentage remains. This remaining percentage is known as moisture content (mc). If timber is not properly seasoned, it will warp, twist, shrink excessively and be more prone to rot. Commercially, timber is seasoned before it is sold.

The required moisture content varies between 8 and 20% and should be equal to the average humidity of the room or area in which it is to be fixed. 10% mc is suitable for timber in centrally heated buildings; and 10 to 14% in buildings without central heating. E...