![]()

1

Job-Embedded Professional Development: An Overview

In This Chapter…

- Professional Development Is Learning

- Job-Embedded Learning—A Brief Overview

- Collaboration and the New Arrangement of Teachers’ Work Days

- Self-Efficacy, Human Agency, and Teacher Voice

- Professional Development Loops Back to Student Learning

- Collaborative Professional Learning—We Know It Works!

- Organization of the Book—Collaborative Approaches to Job-Embedded Professional Development

- Case from the Field

- Chapter Summary

- Suggested Readings

Teachers grow, evolve, and emerge throughout their careers and the day-to-day work they do, and that is why job-embedded learning opportunities need to be the focal point of our efforts. Teachers need to champion their own professional learning in tandem with collaborative and reflective approaches with colleagues, so that job-embedded professional development becomes part of the work day. Gulamhussein (2013a) makes it clear:

Professional development can no longer just be about exposing teachers to a concept or providing basic knowledge about a teaching methodology. Instead, professional development in an era of accountability requires a change in a teacher’s practice that leads to increases in student learning. (p. 6, emphasis in the original)

Learning is about change and as a result of engaging in professional development, it would be a reasonable expectation that regardless of its form, teachers would be “doing something” however big or small differently, that there would be shifts occurring in instructional practices, and that, in turn, there would be shifts in what students would be doing.

Why are collaborative and reflective approaches to job-embedded learning needed? The answer to this question is a clear-cut one—these approaches work! Professional development is learning nestled in the daily arrangements of teaching and the work day, extended beyond the school day, or even across the globe through participation in professional learning networks.

Teachers need to believe that they can be successful, that they can be lifelong learners, and that their students can learn more if they are actively learning alongside them. Teachers need to feel a sense of self and collective efficacy that they can make a difference (Derrington & Angelle, 2013). Teachers also need a voice in determining what they learn, the types of learning activities that will meet their particular needs, and they need to feel a sense of human agency that they can, indeed, make a difference and enact changes in their classroom and perhaps beyond (Bangs & Frost, 2012; Frost 2011).

Teachers need to be part of a community that embraces multiple points of view, the varied experiences, and far-reaching support that can come from colleagues who are willing to engage in collaborative conversations, ask probing questions, and reflect about the impact of such efforts. This chapter examines some important ideas that influence teacher involvement in collaborative and reflective forms of professional development.

Professional Development Is Learning

Professional development is about learning—learning for students, teachers, and other professionals who support children. Learning to teach is a lifelong pursuit, but it is the quality of the professional learning that counts if we want to ensure learning to teach occurs across the career span. A long-term view about the type, intensity, and duration of professional learning is necessary given the link between teacher effectiveness and student achievement. Gulamhussein (2013b) reminds us that:

traditional forms [of professional development] operate under a faulty theory of teacher learning. They assume that the only challenge facing teachers is a lack of knowledge of effective teaching practices. However, research shows that the greatest challenge for teachers doesn’t simply come in acquiring knowledge of new strategies, but in implementing those strategies in the classroom. (p. 36, emphasis in the original)

Professional development that does not include ongoing support through such forms as coaching, opportunities to engage in action research, dedicated conversations with colleagues during team meetings, and other forms of collegial support is, according to Sparks (2013), a form of “malpractice.”

One can hardly blame the bad rap that professional development gets, where teachers are held as a “captive audience” for an extended time, engaging in “notoriously unproductive” and fragmented activities (Nieto, 2009, p. 10), in which the content of these sessions holds little promise for immediate transfer to improved instructional practices (Joyce & Showers, 2002).

So let’s cut to the chase: What do we know about effective profes sional development? As overview, Creemers, Kyriakides, and Antoniou (2013) share:

The research findings have revealed that professional development is more effective if the teacher has an active role in constructing knowledge (teacher as action researcher), collaborates with colleagues (collective critical reflection), the content relates to, and is situated in, the daily teaching practice (emphasis on teaching skills), the content is differentiated to meet individual developmental needs (linked with formative evaluation results). (p. 51, emphasis in the original)

Professional development promotes learning if there are opportunities to collaborate with colleagues about such matters as student work and common assessments, and there is follow-up such as coaching (Darling-Hammond & Falk, 2013; Darling-Hammond, Weir, Andree, Richardson, & Orphanus, 2009).

Job-embedded learning is the ticket to supporting teachers as they engage in the complexities of their work. Timperley (2008, pp. 6–7) indicates that activities that support learning for adults include a variety of modalities that span, for example:

- opportunities to listen to or view others who have greater expertise modeling new approaches in the classroom

- being observed and receiving feedback

- sharing strategies and resources

- being coached or mentored to implement new approaches

- discussing beliefs, ideas, and theories of practice and the implications for teaching, learning, and assessment

- engaging with professional readings and discussing these with colleagues.

These activities mirror job-embedded learning as they occur in the context of the work day.

Job-Embedded Learning—A Brief Overview

Chapter 3 is dedicated to job-embedded learning, and each chapter focuses on constructs of job-embedded learning that promote collaboration.

Job-embedded learning occurs in the context of the job setting and is related to what people learn and share about their experiences, reflecting on specific work incidents to uncover newer understandings or changes in practices or beliefs. Job-embedded learning occurs through the ongoing discussions where colleagues listen and learn from each other as they share what does and does not work in a particular setting. Job-embedded learning is about sharing best practices discovered while trying out new programs, planning new programs and practices, and implementing revisions based on the lessons learned from practice.

Gulamhussein (2013b) makes an interesting point related to the types of expectations teachers hold for student learning, and she wonders why teachers do not hold the same learning expectations for themselves. Job-embedded learning resonates with “meaning making,” “incorporating prior knowledge,” “making learning social with collaboration and discussion,” and “fostering inquiry” (Gulamhussein, 2013b, p. 37). What an adept parallel!

Job-embedded learning can only thrive in a culture that embraces collaboration as teachers are engaged in a new type of work.

Collaboration and the New Arrangement of Teachers’ Work Days

So what is the new work of teachers? The work has really stayed the same—it’s all about the students. New are the arrangements of the work day and how teachers work with one another in and out of the classroom. We are now more focused on students and learning outcomes. We are asking ourselves tough questions: Are students learning, and if they are not, why not, and what can we do to turn things around? Hopefully, we are digging deeper, framing our discussions around students first and then linking our discussions to our practices. These questions and subsequent conversations are occurring in public, collaborative places with peers.

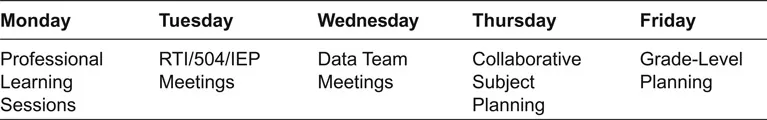

It’s interesting to see how one school leadership team at W. R. Coile Middle School in the Clarke County School District (Athens, GA) has rearranged time every day so that teachers in every grade-level team have consistent time during the contract day where they can collaborate. Figure 1.1 illustrates the schedule that Mr. Dwight Manzy, Principal of W. R. Coile Middle School, has massaged to make collaboration possible.

At Coile Middle School, personal planning time is combined with team planning time, doubling the amount of time for teachers to collaborate.

Collaboration is central to improving student learning. Studies show the connection between professional learning, gains in student achievement, and collaboration (Avalos, 2011; Darling-Hammond et al., 2009; Guskey & Yoon, 2009). The 26th annual MetLife Survey of the American Teacher (MetLife, 2010) examined levels of collaboration as reported primarily by teachers and principals. C. Robert Hendrickson, Chairman of the Board and President and Chief Executive Officer MetLife, Inc., prefaced, in part, this report with the following message:

The 21st century workplace teaches that an education is never complete. There are always adaptations to be made, new things to learn, and opportunities for innovation. Collaboration plays a tremendous role in today’s work environment. Success depends on commitment to a common purpose and working to accomplish more together than can be achieved individually, whether with colleagues down the hall, across the nation or around the globe. (Hendrickson, 2010, p. 3)

Darling-Hammond and Richardson (2009) report “collaborative and collegial learning environments… develop communities of practice able to promote school change beyond individual classrooms” (p. 48).

Figure 1.1. Collaborative Planning and Learning Schedule at W. R. Coile Middle School

Collaboration is a long-term strategy much more enduring than workshops offered by external providers who leave once the “job is done.” This thought is not to infer that collaboration cannot occur as a result of what is learned through external consultants who provide professional learning opportunities. External providers are still valuable, and they can offer much; however, it falls to the system to ensure that there is follow-up support including, for example, coaching, peer observations, modeling, and other mechanisms for teachers to meet and debrief about implementation of new practices.

Systems are getting “smarter” about crafting professional learning oppor tunities. System and site personnel are well poised to tailor the content and professional learning processes and activities because they know and understand the context of the system, the characteristics of the teachers and students, and the climate and the culture within specific buildings. Here too, systems are responsible to ensure that follow-up supports such as coaching, modeling, feedback, reflection, an...