![]()

1

The Evolution of Intelligent Tutoring Systems:

Dimensions of Design

Hugh Burns

University of Texas at Austin

James W. Parlett

Air Force Human Resources Laboratory

Acts of instruction — training, tutoring, teaching — must be integral acts, indivisible, whole. Yet to a designer, they are composed of many interactions — personal, highly collaborative interactions, filled with moments of increasing expertise, of understanding what was not understood, of being challenged to know important things in personally useful and publicly usable ways.

In the 21st century, professional credibility will depend in part on how well educators have kept up with technology in general and the development and use of intelligent tutoring systems (ITS) in particular. Plainly stated, modern educators cannot afford artificial intelligence illiteracy in tomorrow’s electronic schoolhouses. They cannot afford it for their professional lives; they certainly cannot afford it for their students’ futures. An “intelligent” computer is clearly on the practical horizon. Educators and trainers need to be able to exploit it, and — better yet — need to influence the design and evaluation of ITSs. In fact, the credibility of educators as master teachers or tutors depends on moving their future classrooms to singularly, scholarly, social conversations with one human at a time. This, in itself, should not be surprising.

What should be surprising to us today is how far some of the research and developments have come. The literature and scholarship of ITSs is maturing on an international level. To complicate the matter, instructors trained before the widespread use of the microcomputer are often particularly wary of computer-based instruction of any sort. They perceive computer-based instruction, first, as a technology whose time peaked in the 1960s and 1970s and, second, as a symbol of all that mechanizes individual human performance. This bias is unfortunate, but real in all too many instances. This apprehension about technology stands in opposition to another roadblock facing ITS designers, researchers, and implementers. All too often, educators, administrators, and managers of technical training respond to the push of technology overzealously and none too wisely. Although it is disheartening to encounter a schoolhouse of any sort where technology is shunned, feared, or ignored, it is almost equally disheartening to enter a schoolhouse where administrators have responded to the demands of technology by hurling fistfuls of money at the problem with no real conceptual understanding of it. The result, predictably, is a schoolhouse full of fancy hardware platforms, but no design/development staff (or funding for such a beast) in sight.

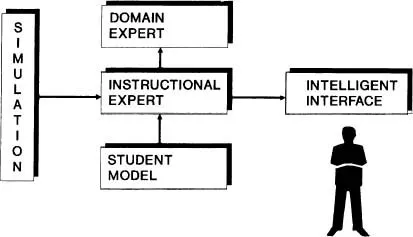

Designing, developing, and evaluating ITSs are not so much strategic matters — what things to do — as they are an integrated technical enterprise — how to do it. Figure 1.1 portrays the overall evolving architecture of a practical intelligent tutoring system.

FIGURE 1.1 Intelligent tutoring system architecture.

It is difficult to separate the dancer from the dance; nevertheless, in Foundations of Intelligent Tutoring Systems (Polson & Richardson, 1988), the foundational anatomy was used to discuss research issues within each of the separate components. These components were an expert module, a student diagnostic module, an instructional module, an intelligent interface, and a user. This classification has allowed the research community to focus attention on issues; for example, representing expert knowledge, designing student bug libraries, developing rules for teacher intervention, presenting intuitive computer work spaces and, for some, preliminary evaluation of ITSs since 1987. Because designing intelligent tutors is such an interdisciplinary activity, attending to the anatomy piece by piece often ignored the synergy that a wholly integrated system could achieve. Now we are wiser and more ambitious. This companion piece to Foundations of Intelligent Tutoring Systems broadens the issues to emphasize the interactivity of the major components in the design and further explores the dimensions of communication, instruction, and expertise.

THE HUMAN-MACHINE COMMUNICATION DIMENSION

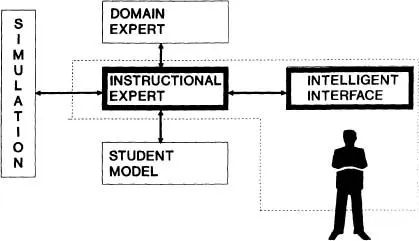

Interactivity is undoubtedly the real strength and centerpiece of individualized instruction necessary to ITSs. The set of instructional activities in an ITS provides miniforums for investigating, exploring, and stimulating the learning processes (see Figure 1.2).

An ITS capable of helping students learn complex problem-solving tasks requires extremely flexible human-machine interfaces. To achieve the goal of designing and implementing flexible tutoring environments, we must begin by defining student-computer interactions; the evolution of system design is moving toward student-centered, reactive learning environments. The microworld design possibilities instantiated are now in “play” or “exploratory” environments capable of being realized in practical interactions in “real” domains. Advances in interface design have allowed us to explore more complex reasoning tasks, so researchers should now focus on the question of developing more formal specification tools that can be used to describe user behavior, independent of software implementation. This methodology resolves the problem of defining functionally equivalent but stylistically different interfaces.

FIGURE 1.2 Communication knowledge architecture.

Ideas about how people learn to read and write should also inform the construction and evaluation of ITSs. More than being able to represent the perspective of student users, more than seeing through student eyes — rather than through the eyes of developers, computer scientists, or domain experts — ITSs will have to be developed so that students who are underprepared in literacy skills have opportunities for success. The literacy demands in the future promise to be even more complex, especially in the area of group or team problem solving. Almost every college and university has already designated a portion of its students as deficient in the reading and writing skills necessary for competent academic work, and the numbers are approximately comparable for the literacy demands in the military. Current research contributing to a new plurality of cognitive and social understanding of literacy emphasizes these basic literacies. What we count as reading and writing or as good reading and writing is going to vary to some extent from context to context. We also know that when people sit down to read or write, they will bring strategies that range from functional to dysfunctional; however, even those reading and writing performances that seem bizarre or quite aberrant have a history and a logic. The notion of a “functional” learning strategy is not new; Van Lehn (1988) and others found such situations to occur often in domains like addition, subtraction, and programming itself. Shaughnessy (1977) theorized that similar “bugginess” was frequently present in the learning behaviors of basic readers and writers — a theory that Hull and Glaser (1989) validated in their research in syntactic remediation. Such ideas applied to the design, development, and evaluation of ITSs suggest simply that we cannot take for granted that our students, particularly those who are underprepared, possess requisite reading and writing skills for special tasks, like operating and learning from ITSs. Thus, we must plan to include bug libraries and strategies for remediation in reading and writing as a natural part of learning literacy practices. Solutions may include students working collaboratively, thus being able to negotiate the meaning and the construction of educational exercises. Other solutions, already in implementation in universities and technical training centers, include early diagnosis and remediation by humans. Computers — ITSs, really — must participate actively in the solution process.

THE INSTRUCTIONAL DIMENSION

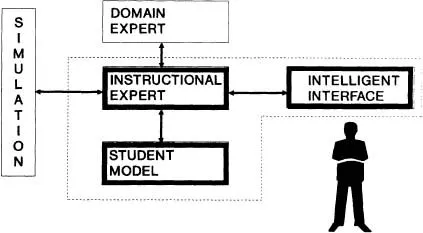

One of the most obvious advantages of an ITS is simply achieving a more favorable teacher-student ratio. Any teacher or coach who is trying to improve performance of a skill can attest that the more one-on-one time spent, the greater the likelihood that a student’s performance will improve (see Figure 1.3). Figure 1.3 depicts the interaction among the instructional module, the student model, and the learner-friendly intelligent interface — the territory where the evolution of the instructional power of a system will take place. So ITSs potentially allow, even require, more one-on-one instructional efficiency and, thereby, leverage more instructional effectiveness.

FIGURE 1.3 Teaching knowledge architecture.

But there are complications, the first complication is an overly simplistic view of instructors as knowledge brokers. Instructors have knowledge of domains, certainly, but instructional effectiveness is more often achieved because of the relationships good teachers have with individual students. Good teachers or tutors are able to take in the instructional context such that they know what the student does not know in terms of knowledge, and perceive what the student can and cannot do in terms of skill. Even trickier is representing the expert knowledge so that the student can comprehend the knowledge while exercising and mastering the skill. All of these instructional practices are often invisible to instructors themselves. The best tutors automatically adjust their relationships with their domain, a specific student, and their instructional repertoire. Make no mistake, ITSs are trying to achieve one-on-one instruction, and therein lies the complexity and the necessary flexibility of any potentially honest ITS design. Burton (1988) discussed at length instructional environments that would have this flexibility; most serious instructional systems following the SOPHIE research legacy have been intended to achieve total instructional robustness (Sleeman & Brown, 1982). So, designing and exploring instructional dimensions of new technologies is perhaps one of the greatest challenges facing ITS implementation. It is certain that the tutor must tutor, and any system that purports to do this effectively will be able to demonstrate a complex set of decisions about what expertise to give, the size of the knowledge to package, and the best way to present such material in the dimensions of time and space. What specific architectures might be proposed for such an instructional integration?

Proposed architectures for representing teaching knowledge in ITSs can be described both in terms of how that knowledge is understood by experts and how it can be represented by programmers in sets of domain-independent tutoring strategies. Teaching knowledge can also be used to develop methods to generate answers and explanations from instructional knowledge bases in which a coherent viewpoint is tailored to the individual student’s needs. From a researcher’s viewpoint, generating explanations is an important goal in the ITS design; what will be curious to see is how explanations are driven by the student diagnostic modules. Let us pursue this idea of explanation generation within the instructional module.

Artificial intelligence (AI) and education have come to be thought of in potentially useful ways, thus ITS designers have set up their own holy grail. The grail is, as you might have guessed, the capability for a large-scale, multiuser knowledge base to generate coherent definitions and explanations. It goes without saying that if a student asks a reasonable question, then an ITS should have an answer. Knowledge engineers are able to predict and write “canned” answers catching students’ questions by recognizing key word patterns and expected terms that need to be defined. But “caning” explanations defeats the intelligence potential for a system to be able to write a program and infer appropriate responses. Most tutors since Socrates have valued questioning and answering instructional strategies. It seems to many of us in AI and education that the true potential for ITS will be in areas where uncertainty is high and information is combinatorially explosive. For example, if there were a knowledge-based expert system on the subject of designing ITS, what questions might be anticipated? An ITS should be able to present fairly easily a definition of an interface. But it would be more difficult for an ITS to generate an explanation to open-ended questions such as “What is knowledge?” “What is the interaction here between student diagnostic modules and expert module?” Simply put, definitions should be easy to present, but often are only useful very early in an instructional interaction. Inferred questioning and explanation generation will take powerful inference engines. Will there be substantial differences in the patterns of acquiring instruction among the various subjects? Of course. Consequently, tools to encode an instructional expert to control knowledge in intelligent tutors will involve representing multiple knowledge concepts and proposing alternative teaching tactics.

Many educators feel that today’s inflexible or brittle software does not significantly help them meet the specific needs of their students. Likewise, educators are not always comforted when computers actually reach their students with appropriate, individual help. It threatens, perhaps, the sense of their own position and authority in the classroom. Much of this brittle software sits on the shelf — abandoned, ignored, unevaluated. If an institution is enthusiastically pursuing advanced computer applications, then such programs are viewed as evolutionary, as improvable, as buying into teacher-controlled modifications. Instructors want more control over supplementary materials; they want to have authority over software prescriptions. It is appropriate for them to have that authority. Because they want the capability to reinforce their students personally, instructors should be able to customize software. These ITSs should be electronic mirrors, reflecting what students want to do and allowing them to think more about their choices, but simultaneously reflecting the shifting and flexible notion of a teacher’s goals. In whatever way an instructor perceives the art of skill development, an ITS must allow more individual opportunities for instructors to intervene precisely in the learning process.

Although some of the brittleness and inflexibility is the fault of designers working in the tight memory constraints, some fault also rests in the politics of ITS development, especially in the academic arena. Many tutoring systems are begun by graduate students or postdoctoral researchers whose financial support is, not surprisingly, grant or research-fund based. These systems, although potentially functional, exist (or are brought into existence) to answer specific research questions, and the system itself is relegated to the shelf when either the research questions are answered or the funding runs out. Designers and research developers are often not motivated or perhaps financially able to excise the brittleness from their systems. Besides, new grants or research questions await them. Technology transition is what is missing.

Technology transition must begin with vigorous evaluation and assessment of the systems. All too often we ignore, gloss, or otherwise sidestep the question: Do these things work? We are not sure whether evaluation and assessment is the work of ITS designers and researchers or the work of (as yet) nonexistent technology transition experts. But such work, as Baker (chap. 11, this volume) points out, needs to be done.

Some ITSs already provide recordings of a student’s problem-solving processes so that stude...