![]()

1

Can CSR Pave the Way for Development?

2.65 billion, or nearly half the people on the planet, live on less than $2 a day and the figures have grown over the past decade. (World Bank Data)

In the seventies I believed that if a company ran an efficient operation with sound staff development, employment, safety and environmental policies, did not bribe anyone, paid our taxes honestly and in the country where income was earned and engaged in a reasonable amount of community development, our responsibilities stopped there. It was the responsibility of government to use the revenue generated. The Economist newspaper still holds to this line. But we now know that where revenue is mis-spent or stolen over long periods by governments, people turn to the company and say ‘You made money, but there is little in the country to show for it.’ To protest that we paid our taxes is of no avail. It may not be our responsibility, but it becomes our problem. If we want the sort of functioning society in which we can do business, we need to work with others to create the capacities and conditions which sound governance requires. (Sir Mark Moody Stuart, Chairman, Anglo American PLC)1

Introduction

If the business of business is business, why should corporations be involved in development? The two quotes above show why. The main proposition of this chapter is that governments and their international arms, the agencies grouped under the umbrella of the United Nations (UN), have failed in their attempts to rid the planet of under-development and poverty. Large corporations with their power and economic strength have taken a dominant position in society. They will, as this book argues, need to take much more responsibility for development than ever before. This chapter will also spell out why development, as seen through the lens of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is a useful tool to promote economic development.

CSR provides a platform for corporations to be involved in economic development in ways that can be much more powerful than has been hitherto thought of. Economic development means improving the well-being of disadvantaged people wherever they may be. Most, of course, can be found in developing countries but many can also be found in the developed and oil-rich countries – the deep south of the US, the north-west of England, the south of France around Marseilles, the poor of Turkmenistan or Uzbekistan; refugees in Saudi Arabia – the list tragically goes on. There is no need, though, for this scandalous situation to be either countenanced or allowed to continue.

The meaning of development

‘Development’ itself is a much maligned term. Until the late 1960s, development was considered by most economists to be the maximization of economic growth. It was really only in 1969 that Dudley Seers finally broke the growth fetishism of development theory.2 Development, he argued, was a social phenomenon that involved more than increasing per capita output. Development meant, in Seers’ opinion, eliminating poverty, unemployment and inequality as well. Seers’ work at the University of Sussex was quickly followed by a focus on structural issues such as dualism, population growth, inequality, urbanization, agricultural transformation, education, health, unemployment, basic needs, governance, corruption and the like, all of which began to be reviewed on their own merits, and not merely as appendages to an underlying growth thesis.3

The main proposition of this chapter is that governments and their international arms, the international agencies grouped under the umbrella of the UN (which also includes the Bretton Woods institutions: the World Bank, International Monetary Fund (IMF) and their newest recruit – the World Trade Organization) have failed in their attempts to rid the planet of under-development, widespread inequalities and poverty. After half a century and US$1 trillion (1000 billion US dollars) in development aid, more than 2 billion people still live on less than $2 a day and, indeed, some of the poorest economies are going backwards.4

Can corporations fill the gap?

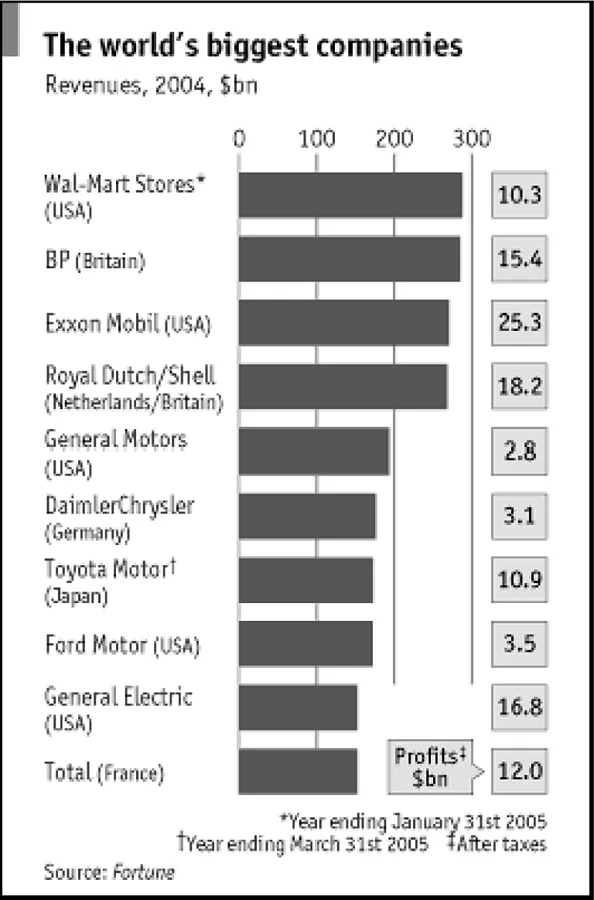

Before addressing the issue of corporations and development, it is worth putting the power of corporations into context. Bestriding the world, these large companies command immense power and reach – the biggest, in terms of revenues as of January 2005, was Wal-Mart which is worth around $300 billion in terms of sales and made $10.3 billion in pre-tax profits in 2004. Most major multinational enterprises (MNEs) are domiciled in the developed world and are owned and controlled largely by citizens of these countries, with 10 of the world’s top 15 companies having their base in the US (Figure 1.1). There are developing world MNEs too, although numbers are small with only around 30 figuring in the Fortune 500 list of largest companies.5 More than in 2001, when an UNCTAD (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development) list of the largest MNEs included only four companies from developing countries – Hutchinson Whampoa, Singtel, Cemex and LG Electronics.6 This trend is expected to continue as companies from developing countries (especially in Asia) increasingly internationalize their operations, not just within the region but also worldwide.

Figure 1.1 Size of top MNEs by country

These figures mean nothing on their own, of course, but note that the World Bank lends around US$15–20 billion a year while the annual budget of oft-cited UN agencies such as the ILO (International Labour Office) is only US$0.25 billion, 100 times smaller than the annual profits of Exxon Mobil for the year 2004 (see Figure 1.1). Both the World Bank and ILO figures are tiny compared with the power and wealth of the largest corporations.

A large portion of world trade – figures vary but some estimates put this at 40–50 per cent – is conducted either within the walls of MNEs or at their behest.7 Their role in development has only recently been acknowledged because it was accepted that corporations were thought to have as their main focus the maximization of corporate profits. To date, corporations have been generous in philanthropic giving – witness the large amounts dedicated and raised for the victims of the Asian tsunami. Around US$400 million was donated by corporations in the US in only a few weeks in early 2005.8 In the UK, according to the London Evening Standard, about US$15 million was contributed by corporations – such as US$3 million from the giant Swiss bank UBS, which set up a UBS Tsunami Relief Fund to bring together individual contributions from staff and clients worldwide. In fact the 500 largest global corporations in 2004 took a record $7.5 trillion in revenue and earned $445.6 billion in profit.9 If MNEs followed governments and contributed even a modest amount on the lines of 0.3 per cent of net income, this would have allocated $13.37 billion for development – just a little less than the World Bank’s annual contribution. Therefore, on the basis of ability to pay, MNEs could if they wanted to.

So size shows, based upon figures for 2004 alone, that MNEs can be a powerful engine for development if, of course, this can be proven to be in their interest and they have the wherewithal to get involved in development. Both these topics will be discussed below, the former under the business case for MNEs in development and the latter under CSR.

It is also worth noting that, according to the KPMG International Survey of Corporate Responsibility Reporting 2005,10 there has been a dramatic change in the type of corporate responsibility (CR) reporting, which has changed from purely environmental reporting up until 1999, to sustainability reporting (social, environmental and economic), and which has now become mainstream among the largest companies. The KPMG report states that:

■ Although the majority (80 per cent) in most countries still issue separate CR reports, there has been an increase in the number of companies publishing CR information as part of their annual reports.

■ At a national level, the two top countries in terms of separate CR reporting are Japan (80 per cent) and the United Kingdom (71 per cent). The highest increases in the 16 countries in the survey are seen in Italy, Spain, Canada, France and South Africa. There have been significant decreases in Norway and Sweden.

■ The typical industrial sectors with relatively high environmental impact continue to lead in reporting. At the global level, more than 80 per cent of the 250 companies examined are reporting in the electronics and computers, utilities and automotive and gas sectors. While, at the national level, over 50 per cent of the 100 companies studied are reporting in the utilities, mining, chemicals and synthetics, oil and gas, forestry and paper and pulp sectors. But the most remarkable is the financial sector, which shows more than a twofold increase in reporting since 2002.

■ The survey, which includes a detailed analysis of the reports of the 250 Global companies, focused on the reasons behind their commitment to corporate responsibility and what influenced the content of the reports. The conclusion that may be drawn is that business drivers are diverse, both economic (75 per cent) and ethical (50 per cent). The top three reported economic drivers are innovation and learning, employee motivation and risk management and reduction, with about 50 per cent of companies reporting these as motivating factors.

■ Independent assurance remains a valuable part of reporting. In 2005, the number of reports with an assurance statement increased to 30 per cent (G250) and 33 per cent (N100) from 29 per cent and 27 per cent respectively in 2002. Major accountancy firms continue to dominate the Corporate Responsibility assurance market with close to 60 per cent of the statements.

Has the UN really failed?

Governments and their main instruments, such as the UN, have failed in tackling under-development. As I will show in Chapter 4, poverty has increased according to certain measures over the past decade. The UN and its agencies are not entirely to blame for the situation, since they must do what their member governments tell them. These, in general, have been incredibly inconsistent over the years with some, such as the US, downright hostile – more on this in . In fact some parts of the UN, the UNDP (United Nations Development Programme) for instance, despite over-programming and bureaucracy, does have a sound knowledge of development, as can be attested in its annual Human Development Reports and associated national publications. But governments have only managed to find about US$1 billion for the UNDP, a drop in the ocean when it is considered that the UNDP works in more than 180 countries.

For instance, the UK’s approach to the UN is one of ‘accountability and transparency’, a mantra that no one can dispute.11 But when one looks in detail at what this means, one finds that the UN and its agencies have increasing difficultly in acting simply because their every action is now double and triple checked. Paralysis cannot be far away.

The assumption, especially after the Iraq ‘oil for food’ scandal, is that the UN and its agencies cannot be trusted and, when they can, that they are inefficient. This does not mean that everything they have done is worthless. Far from it. It is just that the effort has been minuscule in comparison with the resources and technology required.

There was a glimmer of hope that governments may start to take development more seriously than ever before. The UK government placed the problem of under-development as one of the two key issues in the G8 meeting held in Gleneagles, Scotland in July 2005. It addressed at least one part of the problem, that of impoverished nations having huge debts to pay.

The sum proposed by Gordon Brown, then UK finance minister, to settle the debts of some impoverished African countries was significant at US$55 billion. Under the deal, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the African Development Fund would immediately write off 100 per cent of the money owed to them by 18 nations – a total of $40 billion. Brown also said that up to 20 other countries could be eligible if they met strict targets for good governance and tackling corruption.

US$55 billion is only 20 per cent of the market capitalization of General Electric, just one of hundreds of MNEs. Further, many banks and investment brokers have been earning large fees in lending this money to the developing world and receiving interest when corrupt developing world politicians and their cronies transfer their own profits to banks and financial institutions abroad. There is certainly a smile on the face of Swiss bankers – shares of the largest Swiss bank UBS rose 5 per cent during May and June 2005 – partly due at least to the fact that many of their African clients now have deposits but no debts!

And the fact remains that the proportion of GDP going to development from the rich nations has been stuck at around 0.3 per cent ever since the target of 1 per cent was set. The US, for instance, only spends 0.16 per cent of its GDP on development and much of that goes to Israel and Eygpt. Curiously, many of the ‘American people’ are convinced that its government spends 25 per cent of its budget on development aid! (Somberg, 2005)12

When Mayor Giuliani was elected for the first time in New York, he wanted to turn the UN building into an hotel. His aides pointed out very rapidly that...