![]()

1 How to use this workbook

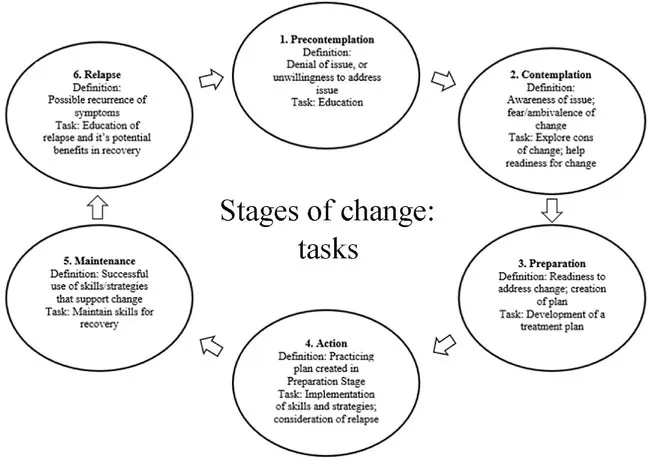

Before you begin your journey to recovery, it is important to understand Stages of Change Theory, and how this information will be used throughout the book. In 1997, Prochaska and Velicer developed the “transtheoretical” model of treatment, based on various theories of psychotherapy with its focus on change as a process. The philosophy behind Stages of Change Theory is that the individual must journey through a series of stages in order to achieve success. Prochaska’s research was initially focused on addiction, but his research and theory has been shown to be instrumental in the treatment of eating disorders (and other psychological struggles) as well.

The impetus for us in writing this book was our own awareness of the increased incidence of relapse upon discharge from inpatient treatment programs for individuals with eating disorders. It was the late 1990s, and, at the time, there were few “partial” or “intensive outpatient programs.” In attempting to understand the high relapse rate for our clients, we saw that they were able to do well when in a highly structured and supportive environment, but on discharge, if they were not in what Prochaska coined the “stage of action,” they were increasingly vulnerable to relapse, which, in turn, brought increased feelings of frustration, disappointment, depression, and anxiety, for both the individual and loved ones. It was this realization that caused us to take a new approach to eating disorders. We believed, and continue to believe, that in order to successfully overcome an eating disorder, we must make sure the individual is truly “ready” to recover.

Throughout this book, we are going to ask you to look at your own stage of change. The stage may be different, depending on the symptom at hand. For example, you may find yourself in the stage of action as it pertains to binge-eating behaviors, but in the stage of contemplation for restrictive eating. We hope that understanding readiness for change may help you better understand why certain journeys are more successful than others. In doing so, we also hope that you will be able to hold onto compassion for yourself while developing a greater understanding of the areas that are holding you back from recovery. In order to use this workbook most effectively, it is first going to be important for you to understand Prochaska’s stages of change:

- Precontemplation: The person refuses to believe there is a problem or is aware of the problematic behavior but refuses to change.

- Contemplation: The person is aware of the problematic behavior but afraid of change. At this stage, it is important to focus on the pros and cons of change.

- Preparation: The person is ready to make changes and is exploring the steps needed to change.

- Action: The person has created a plan to challenge and change the problematic behaviors.

- Maintenance: The person has been successful with the action plan for at least six months, and is working to prevent relapse.

- Termination: The person has little to no concern for a return to problematic behaviors.

The Stages of Change Theory takes into consideration issues of relapse, and although not a “stage” in recovery, relapse helps the person re-focus on the stage of action.

Treatment focus based on stage

- Precontemplation. The person in this stage should receive education on the impact the behavior has on the self and others. It is further encouraged that this person become mindful of the decisions made with regard to behavior and the benefits in changing their behavior.

- Contemplation. The person at this stage should focus on the “cons” of change along with the pros. This awareness, also referred to as the “fear” of change, is critical to understand in order for successful change to take place.

- Preparation. The person at this stage should first create a supportive social network that will help them with behavioral change. The plan for behavior change will be met with concern for failure. The greater the support and awareness of how to act before, during, and after change will likely result in increased readiness for change, thus increased likelihood to keep progressing.

- Action. The person at this stage has experienced some mastery over the behavior and has as the focus the need to fight the urge to slip back. In doing so, techniques learned in the stage of preparation will be important to pay extra attention to during this stage. It will also be important for the person to avoid situations and people that may challenge their current behavioral successes.

Stage of precontemplation

If you find yourself in the stage of precontemplation, the education provided in this chapter will be used as your starting point. We hope it will provide the education needed to help you understand that your views of food and weight are concerning, and could result in significant physical, emotional, and social struggles. If you are already aware of the impact your behaviors and relationship with food are having on you, and yet you do not feel ready to make changes, we ask that you share your awareness with your physician, therapist, or trusted friend/family member. Gaining understanding of the role the eating disorder serves, as well as its impact, is significant to address if you are either in denial of the problematic behaviors or you are aware but and resistant to change.

Stage of Contemplation/Preparation/Action

If you find yourself in any of the stages listed above, we hope that this chapter has helped you not only have a better understanding of the impact food/weight has on your physical, emotional, and social being, but that it has also provided a starting place for you to explore your fears of letting go of your behaviors, while also considering the acts that you are going to employ in order to work toward change and recovery. In the pages to follow, you will find some exercises to help you with your journey from contemplation through action! This is not a linear process, so if you find yourself vacillating between stages, please know this is a common process in recovery.

The goal of the next chapter is to help you develop your own personal plan for normalizing your eating, normalizing your weight, stopping purging behaviors, and restoring your physical and emotional health. It may be difficult at first but the strategies and plans provided have been proved to help people with eating disorders move into recovery.

References

Prochaska, J., Norcross, J., & DiClemente, C. (1994). Changing for good. New York: William Morrow.

Prochaska, J.O. & Velicer, W.F. (1997). The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. S.l.: S.n.

![]()

2 Guiding your Journey

The tree, the web, and the box

Before you begin your own journey to recovery, it is important to understand the role your eating disorder has served. That is, although coined an illness, eating disorders are coping mechanisms. As destructive as they are, eating disorders serve individuals by leaving them feeling protected from something larger and more terrifying than the eating disorder itself.

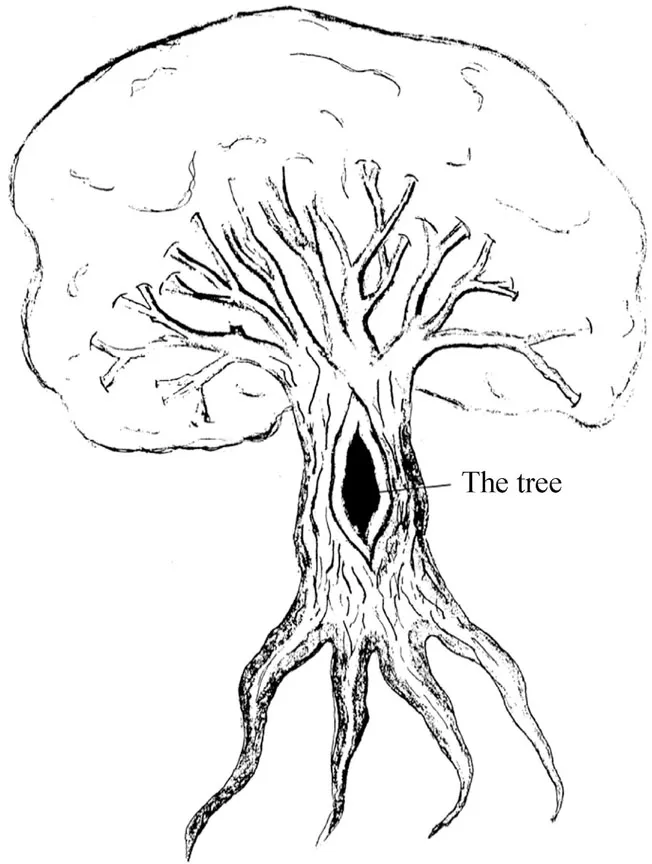

The "Tree"

Eating disorders themselves are never the issue; they are symptoms of a larger issue. Have a look at the diagram of a tree you will find in Figure 2.1. In the diagram, you will notice the tree has many roots; some will be exposed (like those in the deep woods), and some will be covered (like those in a landscaped yard). We have placed the eating disorder in the middle of the trunk of the tree.

In the spaces provided, write what you believe are the roots (some underlying issues) of your eating disorder. Some may be well hidden like the covered roots. Others may be easily seen and understood like the exposed roots. Please feel free to draw grass to cover those roots you feel are not exposed. On the branches, write how the eating disorder has had an impact on you (e.g., weight loss, weight gain, isolation, diminished sexual thoughts and feelings, greater control). Also on the branches write the purposes of the eating disorder. For example: “It decreases my sexual thoughts and feelings”; “I feel powerful and superior when eating less than others”; “I feel finally in control of something in my life”; “Now my ‘outside’ matches my ‘inside’ ”; “I feel empty and devoid of warmth”; “I feel fat and repulsive”; “I’m drying up and dying”; and “I finally feel free of others’ expectations.”

Once you have diagrammed your tree, look carefully at the words that you have written on the roots. These are the reasons for the eating disorder, as you understand them. The eating disorder has protected or shielded you from these issues. Now look carefully at the words you have written on the branches. The branches represent the purposes or the “pros” of the eating disorder. This is why your eating disorder may be hard to give up. It has served one or many purposes.

Sadly, your eating disorder (i.e., your protection . . . your shield) does not come without cost. For some, its cost weighs in forms such as loss of friends, or a missed prom or other events. For others, it results in lost wages, financial distress, or miscarriages. Although it serves a purpose, its costs can be dear and long lasting.

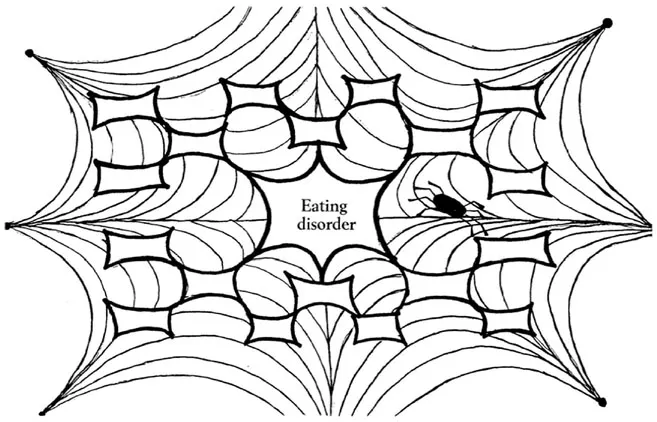

The "web"

In the next figure, you will find the beginnings of a web ( Figure 2.2 ). At its core is your eating disorder. The boxes growing out of the core of the web depict its various “costs.” The illustration will help you draw your web. Our goal is to help you see the costs, or the “cons,” of your eating disorder. What have you lost as a result of your eating disorder?

The web will help you see what price you pay for the eating disorder. We hope your journey to recovery will eliminate the costs and reap you bountiful rewards in health, safety, and happiness. However, this won’t happen until you find another, more healthy and adaptive way, to protect and shield yourself (as represented by the roots) and meet the purposes or pros the eating disorder was meant to meet (as represented by the branches). Your journey through this workbook will help you find more healthy ways to protect yourself while furthering these purposes. As well, it will eliminate the costs you now pay for meeting these needs.

The "box"

Having completed your tree and the web, you should now have a better understanding of some of the underlying reasons of your eating disorder, and its pros and cons. As you continue your journey to recovery, you will find yourself gathering more information, skills, and tools that will aide you in your recovery process. The most difficult part of recovery will be fighting the thoughts and feelings that you will face as you work toward change. For long after you make successful changes with your eating behaviors, the “voice” of the eating disorder will be continuing to create and maintain difficult emotions. When we are in a place of emotional distress, it often difficult to find the clarity to engage in healthy coping strategies; our emotions often take over, resulting in harmful, maladaptive coping responses. The creation and use of a “coping box” can provide a hands’ on solution to healthy management of troubling thoughts and feelings.

How to make a coping box

You will need the following items:

- tissue

- shoe box

- index cards

- items to decorate the box with.

Once you have your box, decorate it to your liking! Make a list of skills you can practice to combat difficult emotions. Examples include: listen to music, talk/text a friend or loved one, play a game, go for a walk (if medically and emotionally appropriate), play with a pet, color/draw, etc. Once you have your list, write each one on a separate index card, and place the index cards inside the box. We recommend you try to have between eight and ten index cards, with no fewer than six. These index cards will help you identify skills in time of need, but will also help you determine your effective coping strategies, as you will see, through practice, what techniques help you work through the feelings and those that do not.

How to use your coping box

When you find yourself wanting to turn to or away from food and/or engage in other eating disordered behaviors, or experiencing difficult feelings such as depression and/or anxiety, we ask that you pull an index card out of the coping box and do what it says to do. Allow yourself 15–20 minutes of engaging in this coping skill. If you find that it has helped you work through some difficult feelings, you have found a new tool for recovery. If after this time, you are continuing to find yourself struggling, we ask that you go back to your coping box, pull out, and practice the new skill recommendation. It is important to note that what may not “work” one time may be the best coping skill under a different set of circumstances. We ask...