1 What exactly is success?

What is the secret of long-term professional success? Is your professional success merely a matter of good fortune, destiny, a logical consequence of your social background, the result of outstanding intellectual abilities and hard work, or is it possibly even pre-programmed genetically? What can we learn in this respect from successful managers and entrepreneurs, and how can this be put into practice? And what is actually the price to be paid for being successful? What are the factors that hinder and impede success? This book addresses precisely these kinds of questions and provides answers that were drawn from various areas of research and complemented by our experience in working with several hundred managers. The results of a study carried out on over 200 managers, entrepreneurs and employees from various English- and German-speaking countries (see Figure 1.0.1) have also been incorporated into this book. The study participants, who were recruited from a wide range of sectors, were asked questions related to success and failure, and about how they had dealt with their own setbacks.

Figure 1.0.1 Overview survey: career level and socialisation.

Source: Survey by Karsten Drath Dec 2015–Jan 2016.

Anyone wishing to explore the rules of success must first of all determine what success and, more specifically, what professional success is. This might, at first glance, seem easy. But, if we take a closer look, a different impression arises. Success might, for instance, be described as the achievement of goals or the sum of right decisions taken. Does this already capture its essence? And above all: Are these definitions universally applicable? In the field of psychology, success is broken down into objective and subjective aspects:

Objective aspects are recognisable to outside observers and are based on social norms and expectations. They include money, influence and status.

By contrast, subjective aspects of success are geared more towards the individual’s values and convictions, including, for instance, self-fulfilment and the purpose or meaning behind their actions.

In the research undertaken for this book, the participants were asked to choose their own personal top 10 criteria for professional success from a list of 26 objective and subjective success factors. The results were very interesting and clear differences could be observed depending on the participant’s career level. In order to simplify things, I have broken down the individual evaluations into the following clusters:

Objective factors: status, power, money

Subjective factors: development, balance, time

Subjective factors: meaning, creativity, growth.

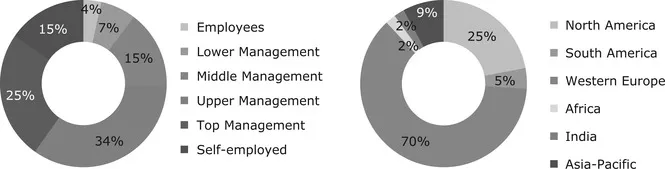

Figure 1.0.2 Objective factors: status, power, money.

Source: Survey by Karsten Drath Dec 2015–Jan 2016.

What is noticeable about the objective factors (see Figure 1.0.2) is that the importance of standing out from the crowd was evidently related to a manager’s career level. It, therefore, seems that once the need for status has been satisfied, this aspect quickly fades into the background. The same is true for wielding power and influence.

However, the aspect of being financially independent gains in importance. It grows steadily, the further someone advances in their career. Even among top managers, it is still considered to be the most important criterion, along with being happy.

Leading other people plays a consistently important role at all levels. At the upper management levels, the factor of promoting other people is also considered to be important, as we shall see.

To create something enduring is still important for managers at the lower end of the career ladder. The main focus here is probably not the company as a whole, but something more modest like a small team. As a manager’s career progresses, the importance of this aspect declines, only to increase again in top management. This might be explained by the need for managers to advance through the different levels, where for many years they are expected to merely execute orders until they are finally able to become movers and shakers.

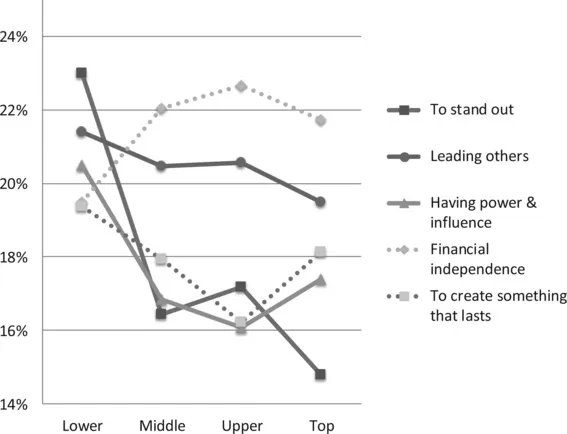

When it comes to the subjective criteria for success regarding meaning, creativity and growth (see Figure 1.0.3), it is noticeable that the idealistic goal of doing good is regarded as much more important at the lower end of the career ladder than at the top.

Figure 1.0.3 Subjective factors: meaning, creativity, growth.

Source: Survey by Karsten Drath Dec 2015–Jan 2016.

Another aspect becomes apparent too: namely that the abstract dimension of finding your calling and meaning diminishes as a manager’s career advances, whilst the concrete dimension of promoting other people becomes increasingly important.

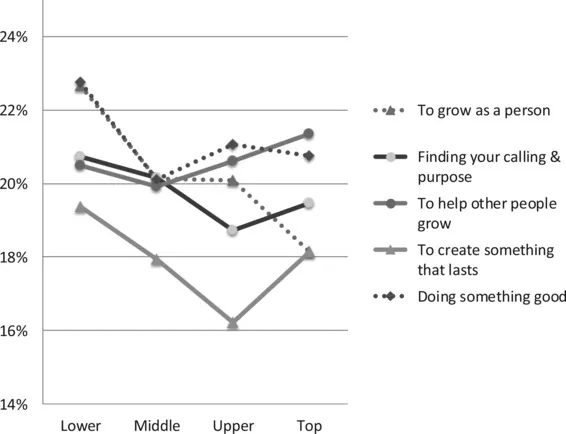

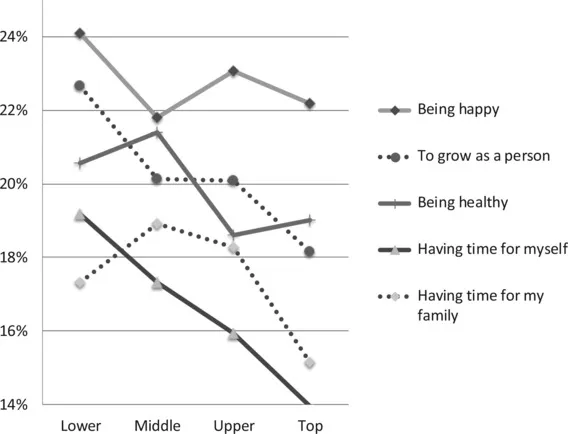

Figure 1.0.4 Subjective factors: development, balance, time.

Source: Survey by Karsten Drath Dec 2015–Jan 2016.

The aspect of personal growth declines as a manager moves up the career ladder. This might have to do with the fact that high-profile managers tend to see themselves as “being in their prime”, whilst managers who are at the start of their careers still very much feel the need to improve their skills.

With regard to subjective factors concerning development, balance and time (see Figure 1.0.4), the distinct impression arises that there is a growing focus on these aspects in the course of a manager’s career.

Both the importance of being healthy and aspects such as having time for yourself or time for the family sometimes diminish markedly in relation to a person’s career level.

I already mentioned the waning significance of the aspects of personal growth. It is only the abstract wish of being happy that never ceases to be important.

From this we might conclude that, in the course of a person’s career, happiness is increasingly sought in connection with promoting other people, financial independence and creating something enduring, while at the beginning of their careers managers will tend to equate happiness with standing out from the crowd, personal growth and doing good.

It was also established that there is a fundamental shift in managers’ expectations regarding work–life balance as they advance towards top management. This may be because their children are grown up and are more independent, and they no longer have to spend as much time at home. However, it is more likely that it is those people, for whom getting the work–life balance right is not a priority, who choose a career in management in the first place.

We can generally conclude that getting the right combination of subjective and objective success criteria is beneficial for executives from all levels when it comes to achieving professional success. Professional success evidently has to do with the simultaneous achievement of personal and social goals. Yet how high the benchmark is set very much depends on your career level and what phase of life you are in. By nature, social goals are relative, in other words they are oriented towards other people. As the proverb goes: “Being rich means either having a lot, or needing little.” Therefore, how much material wealth is needed and how high living standards should be for an individual to see herself as successful in relation to her peer group depend on a variety of factors. For one thing, it is decisive which peer group she chooses to be in. And by this we mean the group of people who are in a similar life situation which she wishes to belong to. It is an inherent part of being a social being that leads us humans to want to be part of a peer group. In the evolution of humankind, this has literally been vital and still is today, albeit from a social point of view.

EXAMPLE

While the relevant peer group for students will be fellow students, it will initially be other job starters for professionals, followed by colleagues and other managers later on. Neighbours and friends may also constitute a peer group. Millionaires compare themselves to other affluent people, film stars to other celebrities, and CEOs to other managing directors.

Apart from the peer group itself, the position one believes oneself to be in or would like to be in, relative to this constructed social group, is also important. Are you striving to be in a group, but don’t yet see yourself there? Or are you part of a group and do you want to remain part of it? Or do you want to rise above the group? The reason we strive for such a position is undoubtedly based on our individual personality traits. Other aspects include, for instance, the local environment we are moving in. What is regarded as a higher living standard in the North Hessian or Lower Franconian provinces is not even considered to be the lower average in cities such as Frankfurt, Munich and Hamburg and their suburbs. So, let us take note that the supposedly objective aspects of success are, in fact, non-existent, since they are geared towards the social and regional environment in which we move.

From this perspective, individual and subjective aspects, such as satisfaction and self-realisation, can be seen as much more objective parameters. Yet, here too, the respective peer group plays a role. So, depending on the peer group, comparing himself with his colleagues might turn a slightly overweight but sporty manager, who is generally happy with his body, into a complete sports nut or into a panting steam engine.

Perhaps we would all feel much more successful and be happier if we compared ourselves less to other people. However, measuring the self against others is a modus operandi of the human mind, and in some ways it can be helpful, too. The inspiration you feel about someone else’s achievements can increase your motivation to improve your own life. The recognition that your abilities are a notch above someone else’s can deliver a boost to your self-esteem. But comparisons can be harmful when they leave you feeling chronically inferior or depressed. Seeing that the path to improvement is attainable is key. You’re better off comparing yourself to someone a rung or two above you than to someone at the very top of the ladder. Loretta Breuning, author of Habits of a Happy Brain, recommends engaging in “conscious downward comparison”. For instance, Breuning says, compare yourself to your ancestors. “You don’t have to drink water full of microbes. You don’t have to tolerate violence on a daily basis. It’ll remind you that despite some frustrations, you have a fabulous life.”

Sonja Lyubormirsky, a psychologist at the University of California, Riverside and the author of The How of Happiness, notes that “people who are happy use themselves for internal evaluation.” It’s not that they don’t notice upward comparisons, she says, but they don’t let such comparisons affect their self-esteem and they stay focused on their own improvement. “A happy runner compares himself to his last run, not to others who are faster.”

The participants in our study were also asked which characteristics and skills were needed to achieve long-lasting success in their career. From 30 factors, they were to choose the top 10 which, in their opinion, formed the basis of a successful career. Figure 1.0.5 shows the attributes and skills which, in the eyes of these top managers, play a central role. Since not all of the factors can be clearly distinguished from one another, e.g. convincing appearance from inspiring others, only the top 15 factors are shown here.

As was to be expected, interpersonal aspects such as empathy, listening to others, making a convincing appearance and inspiring others were considered to be very important by the interviewees. Equally evident was the fact that having specialist knowledge and being intelligent were among the most highly rate...