![]()

1

A Beginner’s Guide to the Television Industry

A. What Is Television?

What is television?

As a threshold matter, understanding the business and law of television requires a working definition of the term. And while the general notion of “television” is no doubt familiar to everybody, a functional definition can prove surprisingly elusive.

Is television a technological medium? In its earliest iteration, television could be understood in essentially technological terms—a telecommunications medium for transmitting audiovisual information via radio frequency electromagnetic waves, typically in the “very high frequency” (VHF) or “ultra high frequency” (UHF) spectrum ranges. Yet from very early in the history of the television industry, alternative transmission media, starting with “community access television” (CATV) systems and later developing into cable and satellite systems (which rely on coaxial cable and microwave transmissions, respectively), challenged the completeness of this purely technical understanding of the term.

Is television definable as a creative medium with certain specific, consistent elements? Certainly, there are creative and production trends which are common to television programming, yet these trends vary and evolve across television platforms and over time, with lines that tend to blur. Program lengths vary. The line between comedy and drama is fluid. Shows may be serialized or episodic. Unscripted television both adopts and challenges traditional notions of television storytelling. “Second screen” experiences delivered via modern consumer electronics now do the same. Television has proven unsusceptible to an all-encompassing creative definition that is responsive to the medium’s evolution over the years. At the same time, the rise of online video distribution, encompassing programming of all types and lengths, generated by a mix of established entertainment powers and individual upstarts, has further challenged any effective effort to contain “television” in a single box.

When commercial television broadcasting began in the early to mid-twentieth century, it was an ephemeral, unrecordable experience; broadcast over the airwaves; covered only a few hours a day (remember test patterns?); featured three principal sources of original content; displayed low-resolution, black-and-white images; and relied on boxes half the size of a refrigerator with screens barely larger than an iPad boasts today. Today, consumers take for granted virtually unlimited viewing options from virtually unlimited sources of content; recording, time shifting, and on-demand consumption; high-definition images sharp enough to see the pores on an actor’s nose; and viewing devices ranging from pocket-sized smartphones to 75-inch high-definition screens with theater-quality sound. How does one unify these wildly different experiences in a single working definition?

This book will use, as its foundation, a brief but expansive definition of “television”: the distribution of audiovisual content to individual consumers, at times and locations and on devices of their own choosing.

This vitally distinguishes television from, for example, theatrical feature film distribution, which essentially requires viewers to go from where they are to the content, rather than the other way around. Yet by this definition (and intentionally so), a YouTube video viewed on a smartphone and a Netflix original series viewed on a computer are no less television than a traditional one-hour drama broadcast on CBS and viewed on a television hooked up to a rooftop antenna.

Beyond the foregoing definition, there are three key consistent characteristics of television programming which are essential to understanding the web of deal structures that bind the television industry together.

First, television is a writer-driven medium. To understand the meaning of this statement, it is helpful to compare the role of the writer in television to that of the writer in the theatrical feature film industry. In television, in the vast majority of cases, the lead creative force behind a series (the “showrunner”) is a writer. This is in contrast to feature films, where the director is typically the “auteur” creative force behind a production. In television, most of the credited producers of a series are writers, who shepherd the project throughout its life-cycle. In feature films, on the other hand, the writer’s role is generally performed entirely during the pre-production phase, and writers have little or no ongoing role in the actual production of their scripts. In television, a pilot script is usually (though not always) written by a single individual or writing team, who conceptualizes the world of the series and takes the studio and network’s notes throughout the series development process. This, too, is at odds with the feature world, particularly that of big-budget studio films, where writing is often effectively done by committee, with new writers commonly being hired to rewrite the work of previous writers, without working in direct collaboration with one another. Finally, in television, a pilot1—and sometimes even a series—is typically greenlit to production on the strength of a pilot script and the reliability of the writers and producers, with actors and directors being hired after the threshold decision to proceed to production has been made. This is also a major difference from feature films, where the attachment of one or more key actors (and typically a director, as well) is virtually always the necessary component that pushes a film project from development into production. The dominant role played by writers in the television industry manifests itself in the process, and the deals, that bring a series to life.

Second, television is a serialized medium. This may or may not be the case in a creative sense—some dramas, such as AMC’s Breaking Bad or HBO’s Game of Thrones, involve complex, arced storylines which unfurl over a period of years (and require that the viewer watch from the beginning of the series to truly follow along), while other types of shows, such as game shows, talk shows, multi-camera comedies (e.g., Two and a Half Men), and procedural dramas (e.g., “cop shows” such as Law and Order) integrate some serialized character or situational development, but can generally be understood and enjoyed in single-episode viewings. But from a production perspective, a successful television series is always an ongoing project, which requires creative and production continuity over a period of years (as distinct from a theatrical feature film, in which cast and crew together come together once, usually over a continuous or semi-continuous period of time, to produce a single closed-ended project). Consequently, the dealmaking framework of television protects the ability of parties to maintain continuity of production and distribution over a period of years.

Third, television as a business relies on a dual revenue model. In general, entertainment economics can be divided into two categories—“direct pay” and “advertiser-supported.” The classic “direct pay” system is the theatrical feature film, in which viewers go to a movie theater and pay for a ticket in order to gain access to the product, with a one-to-one relationship between viewers and tickets. The classic “advertiser-supported” model is exemplified by terrestrial radio, in which entertainment is made freely available over the airwaves and collecting user fees is virtually impossible, so the money that makes the industry run comes from advertisers, who pay for the opportunity to convey their messages to customers.2 The modern television ecosystem, however, features a combination of “direct pay” (in the form of transaction and subscription fees from viewers) and “ad support” (with advertising remaining a dominant presence on most television platforms). In the long term (and as explained in greater detail in the chapters that follow), regardless of its initial distribution platform, virtually every piece of television content produced today is made viable through a combination of “direct pay” and “ad-supported” revenues.

B. Who Are the Players (and How Do They Interact)?

Who made the successful television series, House of Cards?

If you answered “Netflix,” you would be wrong. Netflix exhibits House of Cards throughout most of the world, but the show was actually produced (and owned) by a company called Media Rights Capital, which is known primarily for its feature films such as the raunchy talking-bear comedy Ted (2012) and science fiction epic Elysium (2013). For House of Cards, Netflix acts in the role of a “network,” while Media Rights Capital functions as a “studio” and “production company.” This distinction is one of the centerpieces to understanding how television is created and monetized.

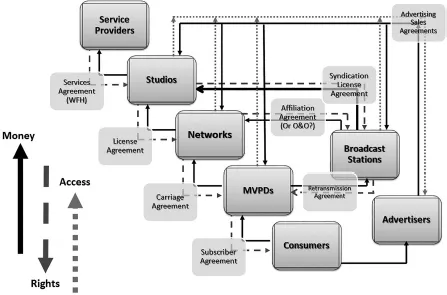

Like many other industries, the television industry is comprised of a series of independent actors with specialized roles who engage in transactions by which, collectively, they develop, produce, market, and distribute a product to consumers around the world. And, as in many other industries, the precise role played by all of the players is sometimes opaque to the consuming public. The following chart visualizes the major categories of entities in the television industry and the essential types of agreements that bind them to one another:

Chart 2 Structure of the Television Industry

In Chart 2, money generally flows upwards (via the solid black lines); intellectual property rights generally flow downwards (via the dark grey dashed lines); and access to the consumer (both via traditional advertising and more contemporary methods, such as product integration) is provided to advertisers (via the light grey dotted lines).

While the television industry (and its product) is certainly unique in many vital respects, it can also be substantially understood by analogy to the development, production, and distribution of traditional manufactured goods—for instance, a smartphone.

i. Service Providers (Talent)

Actors, writers, directors, producers, and other service providers—which, for purposes of this book, will be referred to collectively as “talent”3—are the day-to-day workers of the television industry. While the names and/or faces of the most prominent of these individuals may be familiar to viewers at home, most of these individuals are largely unknown to the general public (though, of course, many aspire to greater recognition and acclaim). In the smartphone analogy, they are the workers on the factory line.

The day-to-day work of developing and producing television content is generally performed by dozens or hundreds of freelance workers who are engaged to lend their expertise and labor to the production process. The most recognizable among these “workers” are so-called “above-the-line” talent—actors, writers, directors, and producers who centrally influence and guide the creative process, and whose names and images may be central to the public’s interest in and recognition of a piece of content.4 In broad, structural terms, however, these high-profile individuals occupy the same type of role as that played by editors, camera operators, electricians, carpenters, and the dozens of other types of crew members who participate in production (generally known as “below-the-line” crew). They are hired and paid for their creative and physical labor, generally on a show-by-show (or even episode-by-episode) basis. They primarily contribute their effort (and the creative fruits of that effort) to a project without making any direct personal financial investment. Consequently, while they may enjoy a financial interest in the success of a project (i.e., “backend”) via a defined “contingent compensation” or “profit participation” formula (discussed in detail in Chapter 6), they generally have no ownership interest in the final product (even if they personally came up with the idea for it).

This category includes not only individual service providers, but also a variety of corporate actors, from physical asset vendors (such as caterers and equipment rental companies) to creative services vendors (such as visual effects companies) to so-called “production companies.” Within this last category, companies may focus primarily on physical production (meaning the day-to-day management of all of the human and physical resources that go into the production process) or creative development (identifying, developing, and selling ideas or intellectual property as the basis for production). In many instances, such creative production companies are closely aligned with, or may even be a mere “vanity shingle” for, prominent individual members of the talent community. For instance, Amblin Entertainment is the production company founded and controlled by director Steven Spielberg, Smokehouse Productions by multi-hyphenate George Clooney, and Appian Way by actor Leonardo DiCaprio. Other prominent production companies such as Anonymous Content, 3Arts, and Brillstein Entertainment Partners are primarily talent management companies with deep rosters of successful writers as clients, which often results in these companies (and/or their principals) becoming attached as producers to their clients’ projects. Although these companies may invest a limited amount of capital in their own salaries/overhead, or in preliminary development activity, they seldom provide direct at-risk production financing for projects, and often lay off their overhead costs onto studio partners5 while recouping development costs from production budgets when projects actually proceed to production.6

These parties are generally in direct contractual relationships with studios, and although the details of these deals vary depending on the role these parties play in the development and production process (with some examples discussed in detail in Chapter 5), the unifying thread is that the studio that engages and pays a service provider is the owner of the results and proceeds of the service provider’s efforts, as a work-made-for-hire under copyright law.7 This status effectively empowers the studio to do whatever it wants with the product, in perpetuity.

ii. Studios

Studios may be the most important players in the television industry that consumers know little or nothing about. These companies are at the center of the development and production of television content—sourcing ideas for shows from the talent marketplace, hiring and paying service providers, financing and managing production of shows, and generally owning the resulting intellectual property—but cultivate little relationship directly with consumers. In the smartphone analogy, they are the Chinese factories/manufacturers of the smartphone (e.g., Foxconn, the Taiwan-based manufacturing company which owns and operates the factories that produce Apple’s iPhone).8

Studios operate a high-risk/high-reward business. Although much of the labor of production is outsourced to service providers who are engaged for active projects, rather than retained on salary, studios nevertheless operate a high-overhead business, employing significant numbers of full-time executives and support staff. Studios finance or co-finance development expenses for a large volume of projects, only a small percentage of which are ever likely to make it to production of a pilot, let alone a series. This is, in part, because studios depend on networks to order projects to production, and the vast majority of development projects will never cross that hurdle (and therefore never see a return on the studio’s investments). Even projects that make it to production may cause the studio millions or even tens of millions of dollars in losses if they fail to find an audience and are quickly canceled by the commissioning network. But with a major hit such as Friends, Seinfeld, or the CSI franchise, the studio’s profits can easily reach hundreds of millions of dollars—and these major successes are necessary to subsidize the higher volume of projects that fail while the studio is in search of that next big hit.

Studios are an essentially “B2B” (or “business-to-business”) business, engaging in numerous vital transactions with more visible players in the television industry (such as talent, on the one hand, and networks, on the other hand), while often operating more or less invisibl...