1

Introduction

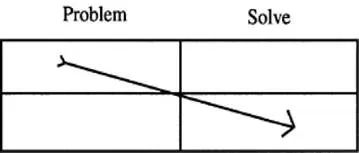

Where do problems come from, and what do we do with them once we have them? The impression we get in much of schooling is that they come from textbooks or from teachers, and that the obvious task of the student is to solve them. Schematically, we have the following model:

The purpose of this book is to encourage a shift of control from “others” to oneself in the posing of problems, and to suggest a broader conception of what can be done with problems as well.1 Why, however, would anyone be interested in problem posing in the first place? A partial answer is that problem posing can help students to see a standard topic in a sharper light and enable them to acquire a deeper understanding of it as well. It can also encourage the creation of new ideas derived from any given topic—whether a part of the standard curriculum or otherwise. Although our focus is on the field of mathematics, the strategies we discuss can be applied to activities as diverse as trying to create something humorous, attempting to understand the significance of the theory of evolution, or searching for the design of a new type of car bumper.

Have you thought, for example, of designing car bumpers that make use of liquid or that are magnetized, or shaped like a football? The creation of air bags suggests yet another option that was not available to us when the first edition of this book was published: that bumpers might be capable of inflation on impact. Or, have you thought of the possibility that they may be made of glass, the fragility of which might discourage people from driving recklessly or relying so heavily on the use of the automobile?

In addition to teaching explicit strategies for problem posing, there is an underlying attitude toward “coming to know” something that we would like to encourage. Coming to know something is not a “spectator sport,” although numerous textbooks, especially in mathematics, and traditional modes of instruction may give that impression. As Dewey asserted many years ago, and as the constructivist school of thought has vigorously argued more recently, to claim that “coming to know” is a participant sport is to require that we operate on and even modify the things we are trying to understand.2 The irony is that it is only in seeing a thing as something else that we sometimes come to appreciate and understand it. This attitude is central to the problem posing perspective developed in this book—found especially in chapter 4 and beyond as we explore what we have coined a “What-If-Not” stance.

Our strategy in this book for revealing and analyzing issues and ideas is generally an inductive one. Whenever possible, we attempt first to expose some problem posing issue through an activity that gets at it in an implicit and playful manner. After there has been some immersion in an activity, we turn toward a reflection on its significance. We believe that it is necessary first to get “caught up in” (and sometimes even “caught,” in the sense of “trapped by”) the activity in order to appreciate where we are headed. Such a point of view requires both patience and also an inclination to recover from discomfort associated with being “caught.”

One way of gaining an appreciation for the importance of problem posing is to relate it to problem solving—a topic that has gained widespread acceptance (or rejuvenation, depending on your point of view). Problem posing is deeply embedded in the activity of problem solving in two very different ways.

First of all, it is impossible to solve a new problem without first reconstructing the task by posing new problem(s) in the very process of solving. Asking questions like the following, propel us to generate new problems in an effort to “crack” the original one: What is this problem really asking, saying, or demanding? What if I shift my focus from what seems to be an obvious component of this problem to a part that seems remote?

Second, it is frequently the case that after we have supposedly solved a problem, we do not fully understand the significance of what we have done, unless we begin to generate and try to analyze a completely new set of problems. You have probably had the experience of solving some problem (perhaps of a practical, nonmathematical nature) only to remark, “That was very clever, but what have I really done?” These matters are discussed with examples in chapter 6.

Recently a teacher was overheard to announce: “When I want your questions, I’ll give them to you.” Much of school practice consists of giving definite, almost concrete answers. Perhaps boredom sets in as answers are given to questions that were never asked.3

More than boredom is at stake, however, when we are robbed of the opportunity of asking questions. The asking of questions or the posing of problems is a much more significant task than we are usually led to believe. The point is made rather poignantly in the story of Gertrude Stein’s response to Alice B.Toklas, on Gertrude’s death bed. Alice, awaiting Gertrude’s legacy of wisdom, asked, “The answers Gertrude, what are the answers?”—where-upon Gertrude allegedly responded, “The questions, what are the questions?”

The centrality of problem posing or question asking is picked up by Stephen Toulmin in his effort to understand how disciplines are subdivided within the sciences. What distinguishes atomic physics from molecular biology, for example? He points out that our first inclination to look for differences in the specific content is mistaken, for specific theories and concepts are transitory and certainly change over time. On the other hand, Toulmin commented:

If we mark sciences off from one another…by their respective “domains,” even these domains have to be identified not by the types of objects with which they deal, but rather by the questions which arise about them.. Any particular type of object will fall in the domain of (say) “biochemistry,” only in so far as it is a topic for correspondingly “biochemical” questions.4

An even deeper appreciation for the role of problem generation in literature is expressed by Mr. Lurie to his son, in Chaim Potok’s novel In the Beginning:

I want to tell you something my brother David, may he rest in peace, once said to me. He said it is as important to learn the important questions as it is the important answers. It is especially important to learn the questions to which there may not be good answers.5

Indeed, we need to find out why some questions may not have good answers. For example, the questions might seem foolish or meaningless; or it might be that the questions are fundamental, personal human questions that each of us fights a lifetime to try to understand; it may be that they are unanswerable questions because they are undecidable from a technical point of view—an issue in the foundations of mathematics associated with Gödel6; might also be, however, that our perspective on a problem is too rigid and we are blinded in our ability to see how a question might bear on a situation.

The history of every discipline—including mathematics—lends credence to the belief not only that it may be hard to distinguish good questions from bad ones in some absolute sense, but that very talented people may not be capable of seeing the difference even for a period of centuries. For a very long time, people tried to prove Euclid’s fifth postulate:

“Through a given external point, there is exactly one line parallel to a given line.”

It was only during the latter half of the 19th century that mathematicians began to realize that the difficulty in answering the question lay in the assumptions behind the question itself. The implicit question was:

“How can you prove the parallel postulate from the other postulates or axioms?”

It took hundreds of years to appreciate that the “how” was an interloper of sorts. If you delete the “how,” the question is answerable (in the negative, it turns out); if you do not do so, the question destroys itself, as is the case with the pacifistic wife who is asked; “When did you stop beating your spouse?”

So far, we have tried to point out some intimate connections between the asking and answering of questions, and between the posing and solving of problems. It is worth appreciating, however, that not everything we experience comes as a problem. Imagine being given a situation in which no problem has been posed at all. One possibility of course is that we merely appreciate the situation, and do not attempt to act on it in any way. When we see a beautiful sunset, a quite reasonable “response” may not be to pose a problem, but rather to experience joy. Another reasonable response for some situations, however, might be to generate a problem or to ask a question, not for the purpose of solving the original situation (a linguistically peculiar formulation), but in order to uncover or to create a problem or problems that derive from the situation.

Suppose, for example, that you are given a sugar cube or the statement, “A number has exactly three factors.” Strictly speaking, there is no problem in either case. Yet there are an infinite number of problems we can pose about either of the situations—some more meaningful than others, some more significant than others. As in the case of being present with a problem, it is often impossible to tell in the absence of considerable reflection what questions or problems are meaningful or significant in a situation. We hope to persuade you, in much of what follows, that concepts like “significance” and “meaningfulness” are as much a function of the ingenuity and the playfulness we bring to a situation as they are a function of the situation itself. Frequently, a slight turn of phrase, or recontextualizing the situation, or posing a problem will transform it from one that appears dull into one that “glitters.”

In addition to reasons we have discussed so far, there are good psychological reasons for taking problem posing seriously. It is no great secret that many people have a considerable fear of mathematics or at least a wish to establish a healthy distance from it. There are many reasons for this attitude, some of which derive from an education that focuses on “right” answers. People tend to view a situation or even a problem as something that is given and that must be responded to in a small number of ways. Frequently people fear that they will be stuck or will not be able to come up with what they perceive to be the right way of doing things.

Problem posing, however, has the potential to create a totally new orientation toward the issue of who is in charge and what has to be learned. Given a situation in which one is asked to generate problems or ask questions—in which it is even permissible to modify the original thing—there is no right question to ask at all. Instead, there are an infinite number of questions and/or modifications and, as we implied earlier, even they cannot easily be ranked in an a priori way.

Thus, we can break the “right way” syndrome by engaging in problem generation. In addition, we may very well have the beginnings of a mechanism for confronting the rather widespread feelings of mathematical anxiety—something we discuss further in Chapter 8.

This book then represents an effort on our part to try to understand:

- What problem posing consists of and why it is important.

- What strategies exist for engaging in and improving problem posing.

- How problem posing relates to problem solving.

While problem posing is a necessary ingredient of problem solving, it takes years for an individual—and perhaps centuries for the species—to gain the wisdom and courage to do both of these well. No single book can provide a panacea for improving problem posing and problem solving. However, this book offers a first step for those who would like to learn to enhance their inclination to pose problems. While this book does analyze the role of problem solving in education, it does so with a recurring focus on problem posing.

ORIGINS OF THE BOOK

The material for this book was influenced heavily by our experience in creating and team-teaching courses on problem posing and solving at Harvard Graduate School of Education beginning in the mid 1960s.7 In addition to graduate students whose major concern was mathematics and education on both the elementary and secondary school level, on several occasions we had students at Harvard who were preparing to be lawyers, anthropologists, and historians. Subsequently, we taught variations of that course to both graduate and undergraduate students at numerous institutions, including Syracuse University, Dalhousie University, the University of Georgia, the University of Oregon, the University at Buffalo, and Hebrew University in Jerusalem. It is interesting for us to reflect on the fact that we did not originally perceive that we were creating something of a paradigm shift in focusing on problem posing. We thought rather that we were adding a new and small wrinkle to...