- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Medieval Europe 400 - 1500

About this book

This book traces across the millennium of the Middle Ages the gradual crystallisation of a new and distinctive European identity. Koenigsberger covers the Islamic, Byzantine and central Asian worlds in his account which explains Europe's progression from chaos and collapse to the point where it was set to rule much of the world.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Medieval Europe 400 - 1500 by H G Koenigsberger in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European Medieval History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The End of the Ancient World and the Beginning of the Middle Ages, 400–700

The Roman Empire in AD 400

About the year 400 John, bishop of Constantinople, called Chrysostom or ‘of the golden mouth’ because of the eloquence of his preaching, looked with satisfaction on the world around him. ‘Now these vast spaces the sun shines upon,’ he wrote, ‘from the Tigris to the Isles of Britain, the whole of Africa, Egypt and Palestine and whatever is subject to the Roman Empire lives in peace. You know the world is untroubled and of wars we hear only rumours.’

History has a way of making the prophecies of intelligent men look foolish. Indeed, many of St John Chrysostom’s contemporaries, especially those living in the western part of the Roman Empire, did not share his optimism. Nevertheless, no one as yet foresaw the collapse of the whole of the western part of the Empire. Even now it remains at least doubtful whether by AD 400 this collapse had already become inevitable.

There was a number of perfectly good reasons for optimism. The terrible civil wars of the third century had been ended and effective government had been re-established by the emperors Diocletian and Constantine. The fourth century was a period of considerable economic vitality. The rapid growth of Constantinople shows this very clearly; for, unlike Rome which had grown as a centre of administration and hence economically mainly as a centre of consumption, the new capital on the Bosphorus developed also as a trading and manufacturing city. In order to assure the supply of labour after the great losses of population in the plagues of the third century, the emperors had issued laws requiring sons to follow the occupations of their fathers, whether as civil servants, soldiers, craftsmen or peasants. Modern historians have often condemned these laws, but they were not universally effective and they did not altogether prevent social mobility. The army, in particular, was a ladder for the socially ambitious and even a peasant could rise in it to the highest ranks. One, Justin, became emperor.

Plate 1.1 Equestrian statue of the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius (AD 161–80), Capitol Hill, Rome.

The medieval mind was haunted and challenged by the visible survivals of the vanished might of Rome. This magnificent second-century statue was restored and placed on the Capitol by Michelangelo in the sixteenth century, but had been known for many years beforehand. Not until the time of Donatello, at the very end of our period, was a sculptor again able to attempt the formidable task of casting a large bronze equestrian statue (see Plate 6.5).

Even more impressive than the economic recovery of the fourth century was the recovery of morale. Christianity, for centuries the religion of only small groups, had rapidly outclassed all its rivals. More and more of the literary, philosophical and artistic talents of the citizens of the Roman Empire were channelled into the service of Christianity and Christianity, in its turn, acted as a powerful challenge and stimulus to men’s creative abilities. Constantinople became the essentially Christian capital of the Empire, without any of Rome’s memories and traditions of a pagan past.

Christianity was an oriental, i.e. non-Graeco-Roman religion. There were other oriental traditions, too, dormant for centuries under the cloak of hellenistic civilization, which were beginning to re-assert themselves along the shores of the eastern Mediterranean. Most important of these was the belief in the divinity of the emperor whose subjects threw themselves on the ground before his statues and icons. For them Christian and Roman became synonymous terms. The monks and hermits and the holy men sitting on their pillars provided ordinary people with a link with the emperor; for the emperor would listen to the holy men’s interventions and admonitions. This link provided a strong bond of loyalty for the subjects of the eastern part of the Roman Empire and it was one of its greatest strengths. But in the long run it turned out to be a very brittle loyalty when Egyptians and Syrians quarrelled with their emperor over the precise nature of their Christian beliefs. In 400, however, no one could know this.

The west was different. Here pagan traditions were still strong, and it was among the pagan senatorial class of Rome that traditional Roman ideology was revived. Roma aeterna, eternal Rome, the holy city, the centre and high point of all civilization – this was a constant theme in the literature of the time. Later, in a Christianized version, this theme was to dominate the literary, artistic, religious and even political sensibilities of western Europeans for more than a thousand years. More immediately, it played its part in the progressive Romanization of the western provinces of the Empire. The Celtic and Basque languages disappeared from most of Gaul and Spain, and eventually survived only in the remote mountain areas of the Pyrenees and Brittany. They were replaced by a low Latin which, as linguists tell us, was soon to develop the basic linguistic characteristics of medieval French and Spanish, just as was happening with Italian in Italy.

The calm at the end of the emperor Theodosius’ reign and the uncontested succession of his two minor sons, Arcadius in the east and Honorius in the west (395) – this calm which had been the basis of St John Chrysostom’s optimism – was deceptive. Many thoughtful men at the time were aware of impending crisis. The danger from the German barbarians in the north and from the Persians in the east had not passed away. So far they had always been defeated. But would this always be possible in the future?

The resources of the Roman Empire

The most fundamental and also the most urgent problem facing the Roman Empire was that of military defence. But successful military defence depended on the resources of the Empire, on the organization and, hence, effective use of these resources, and finally on the ability and the will of the Roman leadership and of the Roman people to use their resources. How much freedom of choice did they have?

The Roman Empire was a world of cities, Mediterranean ports or towns situated on rivers or estuaries close to the sea. They formed a vast free-trade area, linked by seafaring and by a stable and universally accepted gold coinage. In the cities was concentrated most of the visible wealth of the Empire, its splendid temples and theatres, its palaces, aqueducts and public baths, its market places and the forums with their triumphal arches and rows of Corinthian columns. The technology of the ancient world had reached highly advanced levels in certain fields, especially in building and civil engineering, but also in the manufacture of fine textiles and all sorts of metal implements, tools and weapons. These technical achievements, however, were in 400 already centuries old and there is no evidence that the Roman world was moving in the direction of further technological advance.

The reasons for this failure are neither obvious nor simple; but the very formulation of this problem in this form is modern. Educated Romans of the fifth century would not have thought of it as a failure. They were certainly not averse to the comforts which technology could give them, such as warm baths or central heating; but the concept of increasing wealth by technological inventions that would enhance or even replace human labour by the use of machines – such a concept did not and indeed could not yet exist. There is no evidence that educated Romans thought about such problems at all. Since they were educated they belonged to the class of possessores, the property owners, even if they were relatively poor. Life for them was reasonably comfortable within the existing state of technology and with the services provided by domestic slaves. Perhaps more important still, acceptable social and intellectual ambitions did not include technical investigations or the attainment of personal success through the use of technology. Men became lawyers or politicians and administrators. If they did not wish to pursue such practical careers there was the whole rich world of Greek and Latin literature to entertain them. The schools and universities taught these subjects, as well as philosophy and some theoretical science but, apart from medicine, little applied science and certainly no technology. The rise of Christianity accentuated this tendency, for now many of the most brilliant minds of the age became fascinated with theology. How firmly Roman intellectual traditions were set along these lines is shown by the history of Byzantium: for another millennium this brilliant, sophisticated and enormously vital society continued to live without major technological changes except in the art of war; and even there, the Byzantines took over most of their military inventions from their enemies.

In these circumstances, industrial (i.e. handicraft) production could provide only a relatively small part of the gross national product, the effective wealth of the Empire. By far the larger part was, and could only be, supplied by agriculture. Through the experience of several millennia, Mediterranean farmers had learnt to use different types of soil to best advantage. Yields of wheat, of which alone we have a very few figures, do not of course compare well with the most advanced modern standards, but not badly with those of underdeveloped countries. But, just as in the case of manufactures, agricultural techniques in 400 had hardly changed since the days of the Roman Republic. The most modern agricultural handbook of the period, by Palladius, does little more than repeat the advice given by Pliny and other writers of the early Empire. Total output could therefore only be increased by extending the area under cultivation. But here, too, the limits had been reached. Some areas, such as Syria and North Africa, were indeed better cultivated than at any later time before the mid-twentieth century. But Mediterranean agricultural techniques were not easily adapted to the heavier soils and the colder and wetter climate of western and central Europe. In consequence, the provinces beyond the Alps remained sparsely settled and inefficiently cultivated. There seems to have been a serious lack of manpower. Little is known of the growth or decline of population during this period, but the third century had certainly experienced great losses, through war and epidemics, and it is at least doubtful whether these losses had been made fully good in the more peaceful fourth century.

The Romans were well aware of the importance of agriculture. The upper classes invested most of their wealth in land and drew the greater part of their income from it. Even the revenues of the cities and their officials were derived from land rather than from trade. The Christian churches lived on rents and offerings, usually the first fruits of the harvests. Most important of all, the state had come to rely for its revenues on taxes imposed on the country population, the surplus of the labour of millions of peasants beyond the needs of their own and their families’ subsistence. Put into modern terms, the basic problem of the Roman Empire was that of the distribution of the relatively small surplus of a geographically huge but static economy. There were three sets of claims on this surplus, those of the upper classes for their private consumption, those of military defence, and those of the imperial courts and the civil service. All of them were increasing.

The possessores

The possessores, the property owners who lived on agricultural rents, contributed little to economic production. It is impossible to know how large this class was, and its size in relation to the total population was different in different provinces. But even if this class was relatively small, perhaps 10 per cent of the total population, its total numbers would still have been quite large. Among the possessores there was a quite small number of the very rich, the senatorial class. In the west they were probably even fewer and richer than in the east. Some families had huge estates scattered all over Italy, Africa and Spain. These rich families were not altogether without a social conscience. Those who still lived in the large cities competed with each other in spending money on bread and circuses for the poor. In this way Rome itself could still survive with a largely unproductive population of well over half a million.

But more and more rich men moved out of the slums and unhealthy cities into the country where they built themselves splendid and luxurious villas. Life could still be sweet here, even with the evil-smelling barbarians, as Sidonius Appolinaris characterized them, already at the gates. In his letters this cultured aristocrat has left us a vivid description of the life of the very rich in southern Gaul in the mid-fifth century:

On the southwest side are the baths, hugging the base of a wooded cliff, and when along the ridge the branches of light wood are lopped, they slide almost of themselves in falling heaps into the mouth of the furnace. At this point there stands the hot bath, and this is of the same size as the anointing room which adjoins it, except that it has a semi-circular end with a roomy bathing-tub, in which part a supply of hot water meanders sobbingly through a labyrinth of leaden pipes that pierce the wall. Within the heated chamber there is full day and such an abundance of enclosed light as forces all modest persons to feel themselves something more than naked.… The inner face of the walls is content with the plain whiteness of polished concrete. Here no disgraceful tale is exposed by the nude beauty of painted figures, for though such a tale may be a glory to art it dishonours the artist.1

There were large work rooms and cool dining rooms with mosaic floors and with splendid views on colonnades and gardens and a lakeside harbour.

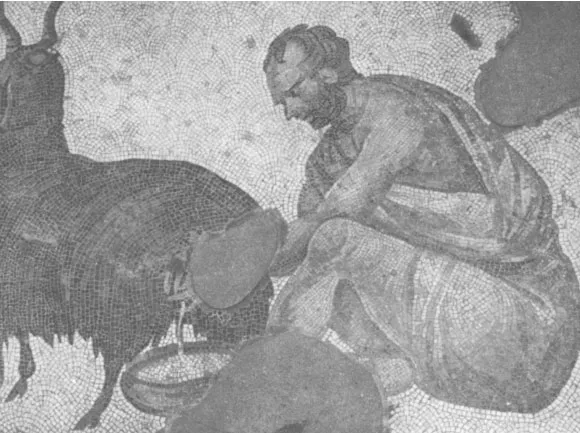

Plate 1.2 The classical tradition of naturalism: farmer milking a goat. Mosaic from the Great Palace, Constantinople.

There was nothing unusual in having this humble, everyday scene depicted on the floor of a palace. The art of making mosaics, i.e. covering floors, walls or ceilings with tesserae – small pieces of coloured stone, tile, glass or some other hard material – was at least a thousand years old at the time and was very popular in Mediterranean villas.

A certain Christian prudery has evidently begun to affect the sensibilities of a Roman gentleman. Greek and Roman tradition, although not without some puritan streaks, had in general accepted the sexuality of men and women as natural. Christianity, developing Jewish and other oriental traditions, virtually equated sin with sexuality, anathematized homosexuality and disapproved of the naked male and female bodies. From the fourth century it became normal that at least bishops, though not yet the rest of the clergy, should be celibate. Monks and hermits in the eastern part of the Empire inveighed against the iniquities of baths and, by an apparently logical extension, also of washing and personal cleanliness. This latter attitude, at least, was not yet acceptable to Roman aristocrats, as Sidonius’ description of his baths makes clear.

Late in life Sidonius became bishop of Clermont-Ferrand (470) and distinguished himself by organizing the defence of that city against the Visigoths. And yet, like many of his class, he urged co-operation between Romans and Goths. It was an attitude compounded both of a genuine conviction of the benefit to the public of such a course and of more narrow class interests. Sidonius judged correctly that the Roman aristocrats would be able to keep their social position and at least some of their estates if they co-operated with the barbarians. When the Empire failed as a shield against the barbarians the Roman aristocracy lost the will to support it further and, once lost, this will could never be recreated. Self-interest and the now developing new links of loyalty came to bind the landowning class to the regional political structures of the barbarian successor states. Only another successful conquest, such as the Romans had initially achieved during the great expansion of the Republic, could have reversed aristocratic loyalties once again. The history of Europe in the next fifteen hundred years is, at least in one of its most important aspects, the history of the attempts and failures to achieve just such a conquest.

An important part of the economically unproductive class of the possessores was the clergy. With the increasing Christianization of the population of the Empire, the number of the clergy and the wealth of the Christian churches also increased. Was this development a growing burden on the limited productive resources of the Empire? It seems at least likely, even though the Church redistributed some of its wealth in the form of alms.

The army

The sums swallowed up by the defence of the Empire had been increasing steadily for more than a century. Diocletian and his immediate successors had doubled the size of the army so that at the beginning of the fifth century it numbered about half a million men. Given the population of the Empire (possibly 50 million) and its very long and vulnerable frontiers, this was not an excessively large number. But to the pay and provisioning of the soldiers had to be added the mi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of maps

- List of plates

- Acknowledgements

- Dedication

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 The End of the Ancient World and the Beginning of the Middle Ages, 400–700

- Chapter 2 The Carolingian Empire and the Invasions of Europe, 700–1000

- Chapter 3 The Recovery of the West, the Crusades and the Twelfth-Century Renaissance, 1000–1200

- Chapter 4 The High Middle Ages, 1200–1340

- Chapter 5 The Later Middle Ages: Transalpine Europe, 1340–1500

- Chapter 6 Medieval City Culture: Central Europe, Italy and the Renaissance, 1300–1500

- Index