- 235 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Human Evolution

About this book

The last decade has seen an explosive burst of new information about human origins and our evolutionary status with respect to other species. We have long been considered unique as upright, bipedal creatures endowed with language, the ability to use tools, to think and introspect. We now know that other creatures may be more or less capable of similar behaviour, and that these human capacities in many cases have long evolutionary trajectories. Our information about such matters comes from a diverse variety of disciplines, including experimental and neuropsychology, primatology, ethology, archaeology, palaeontology, comparative linguistics and molecular biology. It is the interdisciplinary nature of the newly-emerging information which bears upon one of the profoundest scientific human questions - our origin and place in the animal kingdom, whether unique or otherwise - which makes the general topic so fascinating to layperson, student, and expert alike. The book attempts to integrate across a wide range of disciplines an evolutionary view of human psychology, with particular reference to language, praxis and aesthetics. A chapter on evolution, from the appearance of life to the earliest mammals, is followed by one which examines the appearance of primates, hominids and the advent of bipedalism. There follows a more detailed account of the various species of Homo, the morphology and origin of modern H. sapiens sapiens as seen from the archaeological/palaeontological and molecular-biological perspectives. The origins of art and an aesthetic sense in the Acheulian and Mousterian through to the Upper Palaeolithic are seen in the context of the psychology of art. Two chapters on language address its nature and realization centrally and peripherally, the prehistory and neuropsychology of speech, and evidence for speech and/or language in our hominid ancestors. A chapter on tool use and praxis examines such behaviour in other species, primate and non-primate, the neurology of praxis and its possible relation to language. Encephalization and the growth of the brain, phylogenetically and ontogenetically, and its relationship to intellectual capacity leads on finally to a consideration of intelligence, social intelligence, consciousness and self awareness. A final chapter reviews the issues covered. The book, of around 70.000 words of text, includes over 500 references over half of which date from 1994 or later.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter One

Evolution to the advent of the mammals

When did the Universe, as we now know it, and the Earth come into being? When did life first appear on Earth, and when and how did it reach something like the level of multicellular complexity that we see nowadays in the various ecologies of our planet? What is the role of evolution, and how may that process operate in the continued unfolding of life forms? Is there a trend to an ever-increasing complexity, or is that an illusion when viewed from an anthropocentric standpoint? In this chapter we view evolution to the stage of the first mammals.

Formation of the Universe and the Earth

The ultimate questions to be addressed by scientists and religious believers alike relate to the origin of matter and the universe, the origin of life, and the evolution and nature of thought and consciousness, which until recently have been viewed as essentially human. The Universe, according to cosmologists (e.g. Bolte & Hogan, 1995), may be about 16 thousand million (i.e. 16 billion) years old, though uncertainties about the exact age of Hubble’s constant allow for a considerable margin of error (Maddox, 1995; Tyson, 1995). Hubble’s constant enters into the equation linking an object’s distance and its speed of recession, and therefore permits us to calculate when, at the beginning of time, all such objects everywhere in the Universe occupied a single point or singularity. It is possible, however, from features of our galaxy, called globular clusters, to estimate the age of the Universe independent of its age as estimated from its expansion as expressed in the Hubble constant. Chaboyer, Demarque, Kernan, and Krauss (1996) obtained a median age of 14.56 billion years. Other studies (Tanvir, Shanks, Ferguson, & Robinson, 1995), however, propose a lesser figure of between 8.4 and 10.6 billion years.

The difficulty in establishing the exact age of the Earth stems from the fact that there is no geological record for the time between its currently presumed origin (about 4.55 billion years ago), and the time represented by the oldest Earth rocks in the North West Territories of Canada, which have been fairly securely dated to 3.8 billion years of age (DePaolo, 1994), though individual zircon crystals have been dated to almost 4.2 billion years ago. Paradoxically, the best evidence for the exact age of our Earth may come from lunar rocks, the oldest of which is firmly dated at 4.44 billion years. Why should we turn to the Moon in order to date the Earth? The Moon was probably produced from a massive meteorite impact upon the Earth, so the latter must have been in existence when the Moon was formed, and its age must lie between that of the oldest Moon rocks, and that of the oldest meteorites, 4.56 billion years.

Appearance of Life

For living, sentient creatures capable of reflection on such matters, our own existence and that of the Universe we inhabit may nevertheless seem an implausible consequence of an unlikely combination of initial circumstances (Silk, 1997, reviewing Rees, 1997). Why were the density fluctuations in the early Universe of just the right range to permit the formation of galaxies? Why is the nuclear force of just the right strength to permit the formation of stars? Why is the weak force sufficiently weak to enable the formation of elements? Why is the neutron just 14% more massive than the proton, so enabling hydrogen to form? Why does the carbon atom, so essential for life, have an energy level of just the right value to enable its helium “constituents” to be captured before they dissociate in stellar cores? Why is the electron mass, relative to that of the proton, just large enough to permit the formation of larger molecules such as DNA? Is there perhaps an infinity of other, parallel, Universes, of which we clearly cannot be aware, where other constraints incompatible with life occur—or can sentience develop along totally different lines in such Universes?

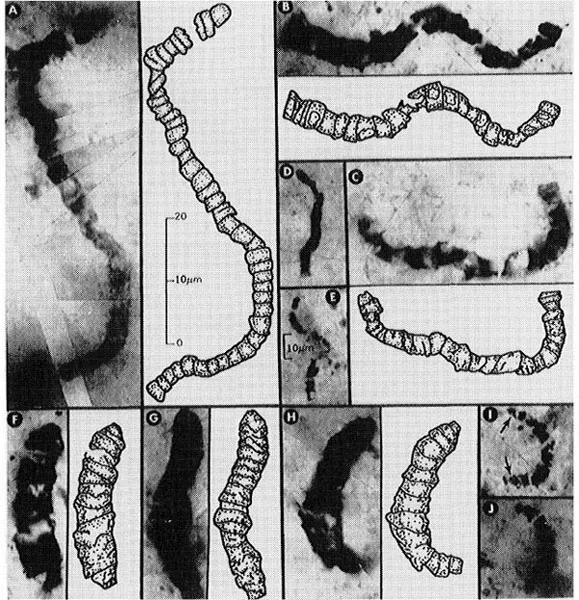

It did not take long for life to appear on Earth. Fossils (see Fig. 1.1) have recently been discovered of microorganisms that had achieved a significant degree of complexity at least 3.5 billion years ago (Schopf, 1993). These filamentous microbes, measuring up to 20 microns in width and up to 90 microns in length, are linked together like beads on a string, and constitute at least 11 separate species. They occur in bedded chert from the Early Archaean Apex basalt of northwestern Western Australia. They are described as prokaryotic, trichromie, cyanobacterium-like microorganisms, or single-celled blue-green algae, and suggest that oxygen-producing photosynthesis had probably evolved even at that early date. Indeed, until 3.9 billion years ago, continued impacts by asteroids may have rendered the Earth uninhabitable. Thus life must have appeared within the remarkably short window of around 400 milllion years, though we should note that the past 400 million years encompasses the entire evolutionary history of vertebrates, from fish to humans. Even that gap may be reduced if the claims of Mojzsis, Arrhenius, McKeegan et al. (1996; see also Balter, 1996, and Hayes, 1996) are substantiated. This group reported grains of apatite (calcium phosphate), containing graphite inclusions, from Akilia Island, the site of Earth’s oldest rocks and dated to 3.87 billion years ago. The ratio of carbon-12 to carbon-13 is near to that typical of living organisms.

Fig. 1.1. Carbonaceous microfossil (with interpretive drawing) from the Early Archaean Apex Chert of Western Australia of 3465 million years ago. Such filamentous cyanobacterium-like microorganisms are among the oldest fossils known. Reprinted with permission from Schopf, J.W., Microfossils of the Early Archaean Apex chert: New evidence of the antiquity of life, Science, 1993, 260, 640–646. Copyright © (1993) American Association for the Advancement of Science.

There is strong evidence that life on Earth divides into three primary domains, Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya, to the last of which we belong (Nisbet & Fowler, 1996). A phylogenetic tree of life has the noteworthy feature that all the most deeply rooted (i.e. earliest) branchings occur between (ancestors of) modern hyperthermophiles, organisms that can only grow at very high temperatures, such as are found in the vicinity of volcanic hydrothermal systems on the ocean floor. A hydrothermal origin of life is also consistent with the fact that metal-binding proteins, especially those involving iron-sulphur clusters and manganese, and those using copper, zinc, and molybdenum, participate in many crucial life processes such as photosynthesis; such elements are abundant in the vicinity of hydrothermal vents. While primitive Eucarya had no mitochondria, higher Eucarya may have incorporated them from purple bacteria, with the acquisition of chloroplasts by Eucarya at or before 1.9 billion years ago (Nisbet & Fowler, 1996).

By 1.9 billion years ago, multicellular algae may have evolved, judging by the appearance in the fossil record of what seem to be their reproductive cysts (Knoll, 1994). Hundreds of specimens of carbonaceous fossils shaped like leaves, tens of millimetres in length and more than a centimeter wide, have recently been found in north China, dated to around 1700 million years ago and resembling modern brown-algal seaweeds. The first well-documented multicellular animals may not have appeared until around 600 million years ago (Gould, 1994). Multicellular architecture then rapidly developed over the next 70 million years. The first such fauna, the Ediacaran, named after a type locality in South Australia, consisted of highly flattened fronds, sheets, and circlets composed of numerous slender segments quilted together. This controversial assemblage is widely held to have died out before the appearance of modern (invertebrate) life forms during the Cambrian explosion (530 to 520 million years ago, see Gould, 1995a). However, we shall see that the Ediacaran fauna did not disappear before the latter climactic event (Grotzinger, Bowring, Saylor, & Kaufman, 1995), but lasted through the basal Cambrian (544 million years ago) and may have contributed to the Cambrian explosion itself (Barinaga, 1995; Palmer, 1996).

Fully meiotic sexual reproduction, in which separate sex cells (egg and sperm) are produced via division and recombination of chromosomes, permits the reshuffling of genes and the potentiality for a vastly greater and faster evolutionary change. However, our impression that life evolves towards ever-greater complexity may be partly due to a parochial focus upon ourselves as lying at the top of the tree of evolution. Similarly our impression that we are somehow the inevitable culmination of evolutionary processes to date stems from a myopic view from our own particular standpoint. Natural selection locates the mechanism of evolutionary change in a struggle between organisms for reproductive advantage. We can only predict the general trends from such a continuing struggle ahead of time in evolution, not the specific details; the actual pathway is strongly undetermined, in that very slight chance changes in initial conditions will inexorably deviate the actual path taken ever further from what might otherwise have happened. Chaos theory makes similar statements, of course, about weather forecasting, the stock example being that the chance occurrence of a minor event (“a butterfly flapping its wings”) in Peking may alter wind-speeds days later in Melbourne; very small initial changes may rapidly amplify to ultimately quite major effects. Evolutionary theory can explain the trajectories taken, but cannot, except in very gross terms, predict them. Traditional evolutionary theory, moreover, has long held that a species changes gradually through millions of years of natural selection—Darwin’s survival of the fittest—until it is so different that it constitutes a new species. Twenty or so years ago the theory of punctuated equilibrium was proposed (Gould & Eldredge, 1993), according to which a new species, especially if a small population is geographically isolated, may abruptly (within say 100,000 years) appear in the geological record after millions of years of apparent evolutionary stasis. Of course, both processes may occur, in different species at different times, and under different ecological circumstances (Kerr, 1995). Be that as it may, individuals die and only the species (itself an artificial and somewhat arbitrarily delimited taxonomic concept) survives, under the constantly changing adaptive pressures of natural selection. Whether the incremental changes which eventually result in the evolution of a mammalian eye or an avian wing occur gradually or abruptly, each adaptation along the way must have been viable and perhaps provided its transient and ephemeral owners with some extra advantage—and not necessarily the same kind of advantage as bestowed by the “final” end product. Thus structures which ultimately became wings, in insects, may have commenced as functional, mobile gills (Averof & Cohen, 1997).

There is, of course, a danger in ascribing all change, even incremental, to the forces of selection, as D’Arcy Thompson observed 80 years ago (see Gould, 1992, in his Foreword to an abridged edition of Thompson’s classic work, On growth and form). Thus physical forces can directly shape organisms; and parts or wholes, even when not so shaped, may take the optimal forms of ideal geometries (e.g. the coil of a shell, the whorl of a sunflower head) as solutions to the problems of morphology. We are similarly cautioned against making up speculative stories about natural selection (and in the following chapters we shall encounter many such accounts attempting to explain the evolution of e.g. bipedalism, or an enlarged brain, and so on), just because gradual transitions may be apparent. The latter may merely reflect a changing set of external forces acting upon unaltered biological substrates. Similarly, some changes must be saltational rather than gradual, just as some geometries can only transform into others via a discontinuity or, as we would perhaps nowadays say, a cusp.

Darwin (1859) viewed evolution from the perspective of the differential survival of the individual organism, adopting a comparatively positive approach to the otherwise ruthless struggle for survival:

There is a grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been and are being evolved. (p. 490)

In prose hardly less compelling, Dawkins (1995) views evolution from the alternative viewpoint of the gene. Our genes are selfish ones that ensured their own survival by enabling their hosts (bodies or organisms) to live long enough to reproduce—genes. However, his conclusion is bleak and profoundly pessimistic:

In a universe of electrons and selfish genes, blind physical forces and genetic replication, some people are going to get hurt, other people are going to get lucky, and you won’t find any rhyme or reason in it, nor any justice. The universe that we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is, at bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil and no good, nothing but pitiless indifference … DNA neither knows nor cares. DNA just is. And we dance to its music. (p. 67)

The thread which links finite and mortal organisms, like beads upon a chain, is of course, whatever standpoint you adopt, their genetic information in the nucleic acids DNA and RNA. The nucleic acids code and specify the amino-acid sequences of all the proteins needed to constitute the living organism. The code consists of specific sequences of nucleotides, consisting in turn of a sugar (deoxyribose in DNA, ribose in RNA), a phosphate group, and most importantly, one of four different nitrogen-containing bases—adenine, guanine, cytosine and thymine in DNA, or uracil in RNA. These four bases constitute a four-letter alphabet, and triplets of bases (letters) form the three-letter words, or codons. There are therefore 43 (i.e. 64) possible permutations of the four bases, and as each DNA codon encodes via RNA and amino acid, the building-blocks of the polypeptides, and, ultimately, the proteins that constitute each individual organism, it might be thought that there would be a corresponding number (64) of such amino acids. That number, however, does not exceed 20; some amino acids can be coded for by more than one codon, while each codon can only specify a single amino acid. DNA mutations are caused by substitutions of one base for another, or by deletions or insertions of bases or of whole stretches of bases.

If genes can influence behavior, they will do so either via the proteins for which they ultimately code, or by regulating the expression of other genes. Either way, at some point they or their consequences will interact with environmental events. There is an ongoing debate concerning the relative contributions of genes and environment to, for example, human abilities or “intelligence” (however defined, see Chapter 9). In general, and for complex functions, genes should not be seen as prescriptive, but along with environmental factors they can powerfully influence both form and function, structure and behavior. In a similar fashion we shall see (Chapter 8) that the size of a brain structure (itself partly under genetic control and partly under environmental influences) does not uniquely determine the extent to which a function, e.g. language, is represented or can be exercised. However, as increasingly indicated by brain-imaging studies, which measure metabolic activity during information processing in a range of tasks, we cannot afford to ignore the correlations that are emerging between form and function in the brain, between variations in the amount of tissue apparently devoted to a particular activity—processing space— and performance levels.

There is an as-yet-unresolved chicken-and-egg problem associated with the original emergence, at the dawn of life, of this system: Nucleic acids can only be synthesized with the help of proteins, and proteins can only be synthesized if a corresponding nucleotide sequence is present (Orgel, 1994). It is very improbable that these two complex structures both arose simultaneously and independently, though it is noteworthy that a protein has recently been built (Lee, Granja, Martinez, et al., 1996) that can in fact self-replicate unaided. This is the first hard evidence that life could have arisen purely from proteins, which in any case are among the best catalysts known. The protein that was constructed was a simple, self-replicating natural protein modeled on one from yeast; it acted as a template to acceler...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Preamble

- 1. Evolution to the advent of the mammals

- 2. Primates to hominids and the advent of bipedalism

- 3. Evolution of the genus Homo

- 4. Art, culture, and prehistory

- 5. Language and communication

- 6. The central and peripheral realization of speech

- 7. Tool use and praxis

- 8. Encephalization and the growth of the brain

- 9. Intelligence, social intelligence, consciousness, and self-awareness

- 10. An overview

- Postscript

- References

- Author index

- Subject index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Human Evolution by John L. Bradshaw in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.