‘A dead man in Deptford’: the Marlowe myth

On Wednesday 30 May 1593, four men spent the day together in a house owned by a woman called Eleanor Bull in Deptford, a town set on the Thames, south-east of London. Ingram Frizer was an up and coming businessman beginning to make his fortune via financial investments in property and commodities. Robert Poley was an agent in Queen Elizabeths secret service who had worked in various shady capacities across the European continent. Nicholas Skeres was another dubious character who had connections with various moneylenders in London, as well as associates in the Elizabethan criminal network. The fourth man in the group was Christopher Marlowe, a young, successful, university-educated writer who had scored a number of notable successes with plays performed at the Theatre and the Rose, two of the early purpose-built playhouses in London. Having spent the day in each other’s company at Widow Bulls, they took supper together and Frizer, Skeres and Poley settled down to a game of backgammon. Marlowe lay down on the bed in the sparsely furnished backroom. Suddenly, a violent dispute erupted between Frizer and Marlowe, possibly provoked by a disagreement over the bill for the day’s food and drink. A fight broke out in which Marlowe beat Frizer around the head with Frizer’s dagger, and in the struggle Frizer regained control of his weapon and stabbed Marlowe in the face, the point of the dagger probably entering the top of his eye socket. Death was instantaneous.

It may seem odd to begin an account of Marlowe’s life at the point of his death. But one of the reasons why Marlowe continues to fascinate, 400 years or more after he died, is because it seems that we know more about his death than we do about his life: the coroner’s report on his death, meticulously detailed, is at the head of a family tree of documentation about the incident. Stories about his death quickly proliferated in a process akin to Chinese whispers: the narrative is embellished with increasingly gruesome detail, becoming more and more outlandish as it is handed from one teller to the next. The coroner’s report clearly identifies Marlowe as the aggressor: ‘it so befell that the said Christopher Morley, on a sudden & of his malice towards the said Ingram aforethought, then and there maliciously drew the dagger of the said Ingram’ and ‘gave the aforesaid Ingram two wounds on his head of the length of two inches & of the depth of a quarter of an inch’ (cited in Wraight & Stern, 1993, p. 293). The report continues:

and so it befell in that affray that the said Ingram, in defence of his life, with the dagger … gave the said Christopher then & there a mortal wound over his right eye of the depth of two inches and of the width of one inch; of which mortal wound the aforesaid Christopher Morley then & there instantly died …

The report makes it very clear how it perceives the killing – that Frizer acted ‘in the defence and saving of his own life’. We will return to this shortly, but it is worth tracing first some of the transformations this story underwent in the years following Marlowe’s death.

Thomas Beard was a Puritan who had been at Cambridge with Marlowe and would later be Oliver Cromwell’s schoolmaster. According to Beard, writing in his book Theatre of God’s Judgements (1597), Marlowe was ‘by practice a playmaker, and a poet of scurrility’ and a blasphemer who had ‘denied God and his son Christ… affirming our Saviour to be but a deceiver … and the holy Bible but vain and idle stories, and all religion but a device of policy’ (cited in MacLure, 1995; pp. 41–2). Incidentally, Beard actually uses the name ‘Marlin’ for Marlowe – as we shall see, Marlowe’s name is as slippery as the stories of his life and death. Beard, rabid in his condemnation of theatre and fanatical in his religious beliefs, must have been oveijoyed to find a man justly punished by God who was not only a playwright but someone rumoured to have been an atheist. Though it is impossible in medical terms, in the light of the report of Marlowe’s wound, Beard maintains that Marlowe ‘even cursed and blasphemed to his last gasp’. So terrible was the manner of Marlowe’s death, according to Beard, that it was ‘not only a manifest sign of God’s judgment, but also an horrible and fearful terror to all that beheld him’ (cited in ibid., pp. 41–2). Pressing the point home, as it were, with all the grim satisfaction of the zealot, Beard concludes:

But herein did the justice of God most notably appear, in that he compelled his own hand which had written those blasphemies to be the instrument to punish him, and that in his brain, which had devised the same.

[cited in ibid., p. 42]

Francis Meres, writing in 1598, refers to Beards account in his collection of jottings, quotations and literary gossip Palladis Tamia. Here, we learn that Marlowe was, apparently, ‘stabbed to death by a bawdy serving man, a rival of his in his lewd love’ (cited in ibid., p. 46). The nature of this ‘lewd love’ is left unspecified, but one possible interpretation is that it is hinting at Marlowe’s reputed homosexuality (Nicholl, 1992, p. 68). Certainly the familiar glib phrase, ‘all they who love not tobacco and boys are fools’, had already passed into the folklore gathering around his posthumous reputation, along with his supposed opinion that Christ and St John were lovers. It would be ill-advised to use these scraps of ‘evidence’ to draw a straightforward conclusion that Marlowe himself was a homosexual, however: to impose modern understandings of sexual orientation onto the early modern period ignores the immense cultural shift that separates us from the Elizabethans. As we shall see when we come to study Marlowe’s historical tragedy Edward II, there were significant differences in attitudes to and conceptions of sexual relationships 400 years ago.

We now have Marlowe cast as both lewd and heretical. William Vaughan, writing some years later (The Golden Grove, 1600), adds some gruesome detail: ‘he stabbed this Marlow into the eye, in such sort, that his brains coming out at the dagger’s point, he shortly after died’. He also reinforces the idea that Marlowe’s death was an act of God: ‘Thus did God, the true executioner of divine justice, work the end of impious Atheists’ (cited in Wraight & Stern, 1993, p. 307). Another furious religious tirade, blessed with the catchy title The Thunderbolt of God’s Wrath against Hard-Hearted and Stiff-Necked Sinners (1618), the work of one Edmund Rudierd, also drew on Beard, but managed to turn the story into a warning against playwrights and actors in general:

But hearken ye brain-sick and profane poets, and players, that bewitch idle ears with foolish vanities: what fell upon this profane wretch, having a quarrel against one whom he met in a street in London, and would have stabbed him: But the party perceiving his villainy prevented him with catching his hand, and turning his own dagger into his brains, and so blaspheming and cursing, he yielded up his stinking breath: mark this ye players, that live by making fools laugh at sin and wickedness.

[cited in Wraight &: Stern, 1993, p. 307]

Marlowes death, then, is interpreted in a number of different ways: first as a warning against atheism; then, connected with some kind of immoral sexual practice; and now taken as proof of Gods disapproval of the theatre. When we begin to look in more detail at Elizabethan society, we will explore further the opposition to the theatre that existed among certain influential sectors of the population. What is important to notice at this point is the fact that Marlowe’s unusual and untimely end is appropriated for different purposes by different writers. The ‘facts’ of the case mutate as they filter through different accounts. This gives us some kind of insight into how history works – less a collation of facts than a process of telling stories about the past. It is a notion we shall return to when we come to look at the story Marlowe told about the reign of Edward II. But to return to Vaughan’s account: for the Puritans, it seems, the story of Marlowe’s death is underpinned by a notion of God’s hand in human affairs, meting out suitable punishment for the heinous sins of blasphemy and atheism. How Marlowe acquired this reputation is another thread that we will trace shortly. But there is another tale to be told about Marlowe, and in order to unravel it, we need to return to his origins and trace his life from its humble beginnings in Canterbury in 1564.

Early years

Some rudimentary details of Marlowe’s early years can be traced. He was born the son of John Marlowe, a shoemaker in the ancient city of Canterbury, and Katherine, formerly Katherine Arthur. Of their nine children, Marlowe was the second, and the oldest that survived. He was also the only one of the boys to live beyond infancy; four of his sisters also lived to adulthood. We know that Christopher was born in February 1564, but it is after this bare fact that we stumble over the first gap in his biography, and we pick up the story again when Marlowe acquires a scholarship to attend the King’s School, Canterbury, at the age of fifteen (although it may be that he started at King’s before this date). Here Christopher would have received a thorough grounding in Latin and Greek grammar, and some ancient literature. He would have learnt about Roman history, as well as the familiar Greek and Roman legends. Canterbury, situated along the route from Dover to London, was a busy city, and Marlowe would have grown up in a lively atmosphere that was lent by virtue of its position something of a cosmopolitan air. One event it is safe to assume Marlowe witnessed, as a child of nine, was the procession that moved down the High Street in September 1573, as Elizabeth I made her royal visit to Canterbury Cathedral; it is likely that the spectacular pageantry would have made a strong impression upon him (Wraight & Stern, 1993, p. 23). Spectacles of another kind were provided by travelling bands of players – records survive of visits by a number of companies during Marlowes time in Canterbury, among them Lord Stranges Men, a group that would become closely associated with Marlowe’s own work. We know, too, that plays were regularly staged at the King’s School, and although there is no direct proof that Marlowe himself performed, it seems fairly likely that he did. He may well have taken part in performances by students at Cambridge, too: records survive of performances at Corpus Christi College during Marlowe’s time there.

In the winter of 1580, Marlowe arrived in Cambridge as the Archbishop Parker scholar at Corpus Christi College, one of the oldest colleges in the university which itself dates back to the twelfth century. Matthew Parker had been Archbishop of Canterbury from 1558 until his death in 1575. The Cambridge connection came via Parker’s period as Master of Corpus Christi College from 1544 to 1553. Three scholarships were established by the terms of his will (Parker had already set up a number of others), and Marlowe qualified for the first of these, which was set aside for a native of Canterbury educated at the King’s School. University life then was a very different experience from what it is now, as we might expect, but the immensity of that difference may still astound us: the student’s regime actually sounds more like a monastic lifestyle than anything else. Rising at four for prayers at five and breakfast at six, the students would attend a morning of classes lasting until dinner at noon: the first half of the afternoon would be taken up by more classes, leaving the rest of the day for private study. The afternoon classes might often involve attendance at debates: university examinations were conducted orally at this time, with a student required either to attack or defend a particular proposition in a kind of verbal combat with his peers. To receive his BA, the student would have been required to offer four such demonstrations of his skill in debate, two offensive and two defensive. The curriculum was again classically based, with a thorough programme of classical philosophy at its centre. Generally, students resided in college for eleven months of the year, although there were many instances of this rule being broken. Indeed, it appears that some questions were raised over Marlowe’s progress from the BA to the MA element of this degree because of his erratic attendance record. Marlowe lodged in a converted storehouse with three other scholars. Many of the students at Corpus Christi would have been younger than Marlowe, since the usual age for entry was fourteen. Although he arrived at Cambridge in December 1580, Marlowe was seventeen when he formally matriculated in March 1581. A total of six years’ study led to an MA, which Marlowe achieved in 1587. As a Parker scholar, he would have been expected to embark on a career in the church. However, it seems clear that Marlowe had very different ideas about where his future lay. He wrote Dido Queen of Carthage while at Cambridge, as well as some poetry (including translations of the erotic poetry of the Latin writer Ovid) and very probably most of the first part of Tamburlaine the Great.

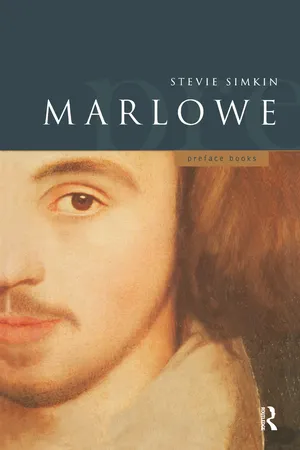

At Cambridge we can locate a number of these fragments of biographical data that make the puzzle of Marlowe’s life so alluring. In 1953, a portrait was discovered amidst a pile of rubble left by builders repairing the Master’s Lodge at Corpus Christi (see the Frontispiece). Charles Nicholl provides some fascinating speculative background to the portrait in his investigation of Marlowe’s death, The Reckoning (1992), and the discussion here of the mystery surrounding it is indebted to that book. Although badly damaged, the painting was sent to the National Portrait Gallery, where it was authenticated as Elizabethan – an inscription bears the date 1585 – and, after restoration, it was hung in the dining hall of the college. Although the painting gives no clue as to who the sitter for the portrait was, it does tell us that the subject was 21 years of age at the time: Marlowe’s age in 1585. As we have already noted, Marlowe entered university unusually late, and it is unlikely that there were many – if any – other students of this age at that time. In 1585, he had received his BA and was embarking on his MA. This makes it more likely that the portrait is indeed of Marlowe. One of the mysteries surrounding the painting is its own history: it does not appear in a list of paintings belonging to the college compiled in 1884. The implication is that it was at some stage taken down and stored away, and then forgotten. Some scholars, assuming it is a portrait of Marlowe, have speculated that it might have been removed in the aftermath of Marlowe’s death and the scandal surrounding the event. Again, speculation piles upon speculation, but there are undoubtedly some good reasons for believing that it might be his portrait. Some of the reasons are soundly and logically based, whilst others are founded on a degree of romanticism that can be hard to resist, particularly when we read the Latin inscription beneath: ‘Quod me nutrit me destruif’: ‘that which nourishes me destroys me’. It is, as we shall see, a haunting and a provocative line, and one that fits conveniently into the Marlowe myth that we are now beginning to piece together; this has made it all the more tempting to assume that it is his portrait.

Trying to reconstruct Marlowe’s time at Cambridge is another game of deduction and speculation, but the most mundane of sources have the potential to offer up rich, intriguing clues, solutions and possibilities. These sources include the college accounts (complete apart from the 1585–6 academic year records, which are missing), which show the payments he received as a Parker scholar, and the Buttery book, which details expenses on food and drink for individual students. Scholars such as Frederick Boas (1940), Wraight Sc Stern (1993, first published 1965) and Charles Nicholl (1992) have studied the patterns of these records (there are photographs of some of the relevant pages in Wraight Sc Stern’s appendices), and made some fairly safe deductions from them. Their conclusions lead us back into the shadows that enveloped Marlowe at Eleanor Bull’s house in Deptford in May 1593. The records of attendance are not extraordinary for the first three years of his university career: a couple of periods of absence lasting six weeks each technically exceeded the college regulations, but were not unheard of. However, the 1584–5 session sees a sudden drop in Marlowe’s total scholarship payments: with the scholarship working on the basis of a shilling a week for every week the student was in attendance, the amounts paid to Marlowe during this academic year total only 195. 6d. The Buttery book fills in some of the detail for us, suggesting that Marlowe was absent for eight weeks between April and June and nine weeks between July and September, returning for the end of the Trinity term. For the next year, the Buttery book is all we have to go on, and it indicates another April-June truancy; and in 1587, college accounts show a further absence of a couple of months by the time the Lent term wound up on 25 March.

Marlowe’s absences had, of course, not gone unnoticed, and he was initially refused permission to proceed from his BA to his MA degree. The decision was overturned by a letter sent to the Cambridge authorities from Elizabeth’s Privy Council:

Whereas it was reported that Christopher Morley was determined to have gone beyond the seas to Reames [Rheims] and there to remain, their Lordships thought good to certify that he had no such intent, but that in all his actions he had behaved himself orderly and discretely whereby he had done her Majesty good service, and deserved to be rewarded for his faithful dealing: their Lordships request was that the rumour thereof should be allayed by all possible means, and that he should be furthered in the degree he was to take this next Commencement, because it was not her Majesty’s pleasure that any one employed, as he had been in matters touching the benefit of his country should be defamed by those that are ignorant in th’ affairs he went about.

[cited in Nicholl, 1992, p. 92]

Scholars have proved fairly conclusively that this Christopher Morley was our Marlowe; I have already noted in the discussion of Thomas Beard’s account that Marlin was one alternative form for Marlowe’s name, particularly in his days at Cambridge; Morley was another. ‘Reames’ is the French city of Rheims where the English College had been established, one of only a handful of Catholic seminaries established in Europe for Englishmen. The rumour that Marlowe had visited Rheims would have implied that he had defected not only in religious terms, from England’s Protestantism to France’s Catholicism, but in political terms too. What the Privy Council’s letter implies is that Marlowe, far from being a political and religious traitor, was in fact a loyal patriot. What we seem to have is a classic example of the undercover agent, working behind enemy lines.