- 386 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Architecture, Power and National Identity

About this book

The first edition of Architecture, Power, and National Identity, published in 1992, has become a classic, winning the prestigious Spiro Kostof award for the best book in architecture and urbanism. Lawrence Vale fully has fully updated the book, which focuses on the relationship between the design of national capitals across the world and the formation of national identity in modernity. Tied to this, it explains the role that architecture and planning play in the forceful assertion of state power. The book is truly international in scope, looking at capital cities in the United States, India, Brazil, Sri Lanka, Kuwait, Bangladesh, and Papua New Guinea.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Architecture, Power and National Identity by Lawrence Vale in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Architecture GeneralPart 1

The locus of political power

Chapter 1

Capital and capitol: an introduction

Political power takes many forms. In addition to the power evinced by a charismatic leader, an indomitable military presence, an entrenched bureaucracy, or an imposing network of laws and statutes, many political regimes make especially powerful symbolic use of the physical environment. Throughout history and across the globe, architecture and urban design have been manipulated in the service of politics. Government buildings are, I would argue, an attempt to build governments and to support specific regimes. More than mere homes for government leaders, they serve as symbols of the state. We can, therefore, learn much about a political regime by observing closely what it builds. Moreover, the close examination of government buildings can reveal a great deal about what Clifford Geertz has termed the “cultural balance of power”1 within a pluralist society.

Much recent writing on architecture and urban design rightly stresses that all buildings are products of social and cultural conditions. This book carries that argument a step further by exploring the complicated questions about power and identity embedded in the design of national parliament buildings and the districts that surround them in various capital cities around the world. It is based upon a simple premise: grand symbolic state buildings need to be understood in terms of the political and cultural contexts that helped to bring them into being. The postcolonial parliamentary complex provides an excellent vehicle for exploring these issues, since it is an act of design in which expressions of power and identity seem explicit and inevitable, both for the government client and for the designer.

How do Government Buildings Mean?

In his essay “How Buildings Mean,” the philosopher Nelson Goodman argues that we must consider the question of how a particular work of architecture conveys meaning before we are able to address the issue of what the building may mean. In so doing, Goodman aims to identify the categories of meaning that the built environment may convey as well as to elucidate the mechanisms by which these meanings are transmitted. This sort of analysis is crucial for understanding the nature of the relationship between the design of a parliamentary complex and its political history. As Goodman notes, “A building may mean in ways unrelated to being an architectural work—may become through association a symbol for sanctuary, or for a reign of terror, or for graft.”2 Such symbolism need not be so architecturally arbitrary, however. Buildings may also mean in ways very much tied to choices made by architects and urban designers.

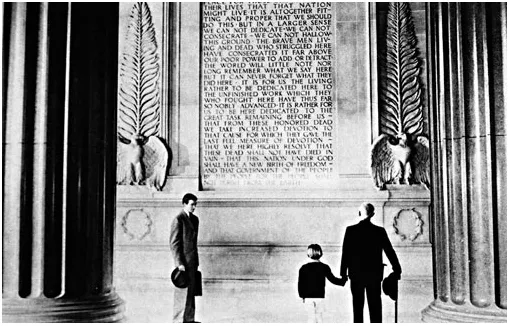

Goodman identifies four such ways—denotation, exemplification, metaphorical expression, and mediated reference—each of which would seem to enhance the possibilities for multidimensional interpretation of government buildings. Some part of a building’s meaning may often be read literally or otherwise directly denoted. In the case of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., for example, meanings are denoted by the extracts from Lincoln’s speeches carved into its walls and by the presence of the large statue of Lincoln himself (1.1). In this most direct of ways, the memorial communicates messages; these messages are, of course, open to multiple interpretations.

1.1 Meanings of the Lincoln Memorial: Lincoln’s words speak directly.

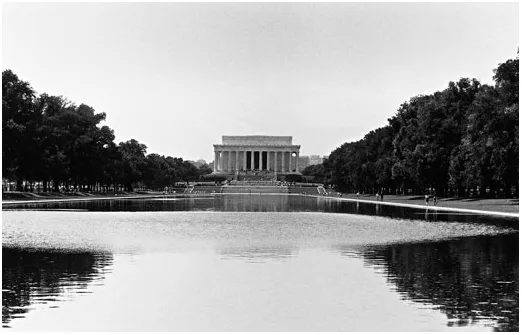

The Lincoln Memorial conveys meaning in a second way by drawing attention to certain of its properties to the exclusion of others. In this view, it is not only a self-contained building but also a dramatic urban design gesture, a terminus that gathers in the linear force of the Washington Mall (1.2). The solid-void-solid rhythm of the memorial’s east facade draws the eye toward its center and the statue, even from a great distance. This mechanism for conveying meaning seems quintessentially architectural.

1.2 Meanings of the Lincoln Memorial: exemplifying some architectonic properties more than others.

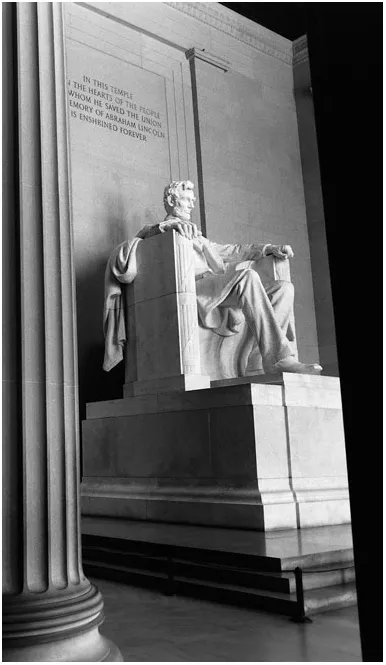

A third way that such a building may mean is through the expression of metaphor. This method is used quite powerfully in the case of the memorial, architecturally treated as a kind of analogous temple, with Lincoln taking the place of the classical deity (1.3). In case the metaphor is missed, however, the message is reiterated quite literally, carved into the wall above the statue: IN THIS TEMPLE AS IN THE HEARTS OF THE PEOPLE FOR WHOM HE SAVED THE UNION THE MEMORY OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN IS ENSHRINED FOREVER.

1.3 Meanings of the Lincoln Memorial: temple as metaphor.

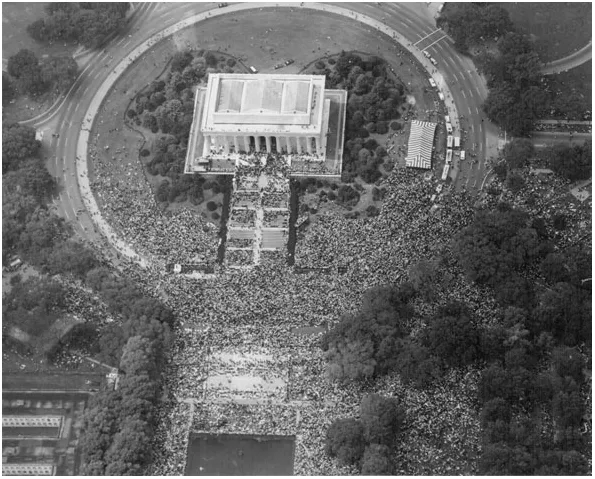

Building on this predilection for metaphor, the Lincoln Memorial demonstrates a fourth way of meaning, that of mediated reference. There is a chain of reasoning that leads from the deification of Lincoln as a savior to broader consideration of the values of national unity and racial equality promoted by Lincoln’s presidential acts. From this, in turn, the memorial becomes associated with the process of advancement of civil rights. It is not by coincidence that many of Washington’s civil rights rallies are held in front of the Lincoln Memorial (1.4).

1.4 Meanings of the Lincoln Memorial: mediated references carry forward broad conceptual associations, from Civil War to civil rights.

Such mediated references may lead the construction of meaning far afield from the detailed physical particularities of the architectural object itself. As Goodman puts it, “Even when a building does mean, that may have nothing to do with its architecture. A building of any design may come to stand for some of its causes or effects, or for some historical event that occurred in it or on its site, or for its designated use; any abattoir may symbolize slaughter, and any mausoleum, death; and a costly county courthouse may symbolize extravagance. To mean in such a way is not thereby to function as an architectural work.”3

Goodman’s distinction is useful for identifying the mechanisms of “how buildings mean,” but it is much less helpful as an analytical tool for understanding the subsequent question of what buildings may mean, since these sorts of nonarchitectural associations seem central to the way that most people think about buildings. What value is there, then, in privileging only those kinds of meanings that are termed architectural? It may be that because these other associative sorts of meanings are so powerful and often so predominant they threaten many architects and others whose professional self-esteem is dependent on their buildings’ being able to communicate effectively their designer’s intentions, whether aesthetic or social. How can a designer defend an exquisite formal gesture if it becomes publicly overshadowed or undermined by the indefensible acts of the building’s institutional inhabitants or by some other historical relationship in which that building may stand?

To focus our concern only on the architectural portions of a building’s meaning takes too limited a view of what is involved in the design of a building. If a goal of this book is to explore the complex meanings of government buildings, then one must treat the political designs of government officials as equal in importance, and often intimately related, to the physical designs of architects. So, too, if an overriding issue is the meaning that these places may hold for diverse segments of the public, one must try not to let interpretation of these buildings be too dependent on specialized knowledge of comparative architectural history and formal precedents. It is here that the mechanisms of metaphor and mediated reference become valuable analytical tools. Even if the average American citizen knows little about the details of classical systems of proportion and cannot comprehend the richness of meanings encoded into an ancient temple’s entablature, that citizen will sense the metaphor of Lincoln as an enthroned deity and will know something of his deeds.

Government buildings would appear to serve several symbolic purposes simultaneously. Some of these meanings may be traceable to a designer’s—or a politician’s—intentions, even if the interplay of ideas within such designer-client partnerships cannot usually be clearly charted or differentiated. Other meanings are not introduced by an individual’s formative act but arise as unintended and unacknowledged products of a widely shared acculturation. In the United States, citizens are socialized to regard the most prominent neoclassical edifices of Washington as the reassuring symbols of such concepts as “equal justice under the law” and government “of the people, by the people, and for the people.” The buildings housing principal public institutions are unconsciously perceived as metonymous reinforcement for an idealized and stable democratic government, worthy of our tacit trust.4 The political scientist Murray Edelman, author of a seminal book on the subject of political symbolism, has argued that such buildings “catalyze the common search for clarity, order and predictability in a threatening world.”5

At the same time, however, the buildings themselves can appear to be part of that threat. “The scale of the structures reminds the mass of political spectators that they enter the precincts of power as clients or as supplicants, susceptible to arbitrary rebuffs and favors, and that they are subject to remote authorities they only dimly know or understand.”6 Moreover, this monumentality may reciprocally reinforce the self-perceptions of those government officials and bureaucrats who identify this exalted territory as their own. In this way, existing hierarchies can be legitimized at all levels, and extremes of power and impotence intensified.

The manipulation of civic space thus tends both to sanction the leadership’s exercise of power and to promote the continued quiescence of those who are excluded. Reassuring civic messages and discomforting authoritarian ones engage in a kind of cognitive coexistence. As Edelman contends, “Everyone recognizes both of them, and at different cognitive levels believes both…. Logical inconsistency is no bar to psychological compatibility because the symbolic meanings both soothe the conscience of the elites and help nonelites to adapt readily to conditions they have no power to reject or to change.”7

Design manipulation that promotes this dual sense of alienation and empowerment occurs at all scales of a country’s civic space, ranging from the layout of a parliamentary debating chamber to the layout of a new capital city. The design of a government building’s interiors holds many clues about the nature of the bureaucracy that works therein. The privileged location of a high official’s office and the gauntlet of doors and security checkpoints one must traverse to reach it help clarify the structure of authority. Or, conversely, the deliberate locating of a leader’s office or principal debating chamber so that it is open to public view (if not public access) may be an attempt to convey a sense of governmental approachability, either genuine or illusory.

Charles Goodsell’s comparative analysis of the layouts of American city council chambers demonstrates how the distribution of political power can be observed even in a single room. Relying on close examination of the relative positions of speaker’s podium, council members’ seating, and public galleries in the design of seventy-five chambers constructed during the last 125 years, Goodsell identifies two basic and interconnected longterm trends in democratic governance: a trend away from “personalistic rule” expressed by “the shift in central focus away from the rostrum’s presiding officer to the council’s corporate existence” and a trend toward the “downgrading of geographic representation” as evidenced by a move from separated aldermanic desks to a common dais table. Equally indicative of evolving attitudes is the treatment of the public. The more illuminating architectural shifts include the reorientation of the council’s seating in such ways that members communicate with the public instead of with each other, the downgrading or removal of barriers between government and public, the addition of increasingly greater amounts of public seating, and the provision of increasingly more prominent public lecterns. Taken together, Goodsell concludes, these and other changes “generally convey concepts of promoting popular sovereignty and democratic rule, of viewing the people as individuals rather than an undifferentiated mass, and of establishing the moral equality of the rulers and the ruled.” To his credit, Goodsell takes his analysis one step further to question whether this seemingly positive visual trend toward increased democracy is, in practice, little more than an insidious deception, an “empty, hypocritical ritualism that only masks the powerlessness of the ordinary citizen.”8

Thus, even in those contemporary council chambers in which government and citizens are spatially conjoined by seating arrangements, it surely seems possible that the dual sense of alienation and empowerment could be reinforced. Moreover, at the level of national government symbolism— the locus of this book’s principal concern—the layout of parliamentary chambers, even contemporary ones, consistently treats the public as detached spectators of governmen...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface to the second edition

- Preface to the first edition

- Part 1 The locus of political power

- Part 2 Four postcolonial capitol complexes in search of national identity

- Notes

- Illustration credits

- Index