![]()

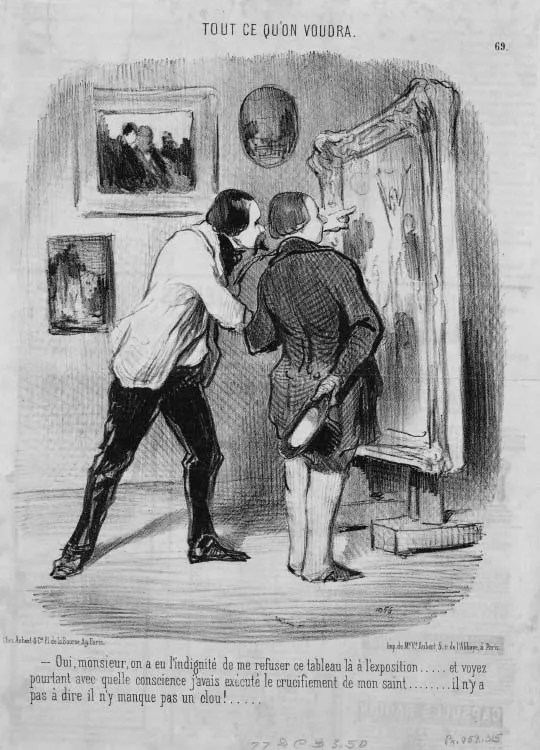

Plate 1 Honore Victorin Daumier: Yes … I have had the misfortune of having this painting rejected … (Oui … On a eu l'indignite de me refuser ce tableau …), number 69 from the series As One Likes It (Tout de Qu’on Voudra), Chez Aubert & Cie, Paris 1851. Lithograph, 32.8x23.6cm. Courtesy of the Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire. Purchased through the Julia L. Whittier Fund.

LIKENESS AND PRESENCE

Images are likenesses made to present things. The photo presents one’s beloved. The painting presents a battle. The sketch presents the lay of the land, and a path back home. The graph presents the relationship between the seasons and sunrise. The diagram presents the relationship between the Earth’s tilt and the onset of summer. The watercolor presents the mountains at dawn, and the etching presents a method for making pictures. Mental images present everything that we encounter perceptually. All of these examples are representations that are likenesses made to present things. They are not made in the same way, and they are not the same kinds of likeness, but they are all images, in the broad sense of the term employed here.

This expansive sense of images casts them as one of perhaps two ways of representing. There are fairly arbitrary pairings of names with things, exemplified in language, and there are representations that present likenesses, exemplified by figurative photographs. Things are complicated, of course. On the one hand, names answer to norms, so they’re not completely arbitrary. The longest place name in Europe, for example, is Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch, which makes it sad, but understandable, that Welsh is a dying language. And on the other, many images, in this broad sense, are harder to read than languages. Only radiologists really understand x-rays, and there are some structural diagrams that can make your head spin. Common hybrids, like labeled maps, show that some representations play two games at once. One goal of this book is to convince the reader that this broad distinction, between the images and mostly arbitrary pairings, is important and worthy of attention despite all the complications.

Philosophers actually agree that there is some broad distinction at work here, but they disagree about where to draw the line, and how important it is. A finer question animates most philosophical work in this area: what is pictorial representation? What distinguishes figurative paintings, photographs, and drawings from other kinds of representation? Sometimes, accounts of depiction fit easily within a broader account of images, sometimes not. Many theories were developed without even a glance at the broader class. This is understandable. First, it’s controversial whether the so-called images are a theoretically interesting kind, rather than a messy patchwork. Second, pictures are terribly compelling all on their own, once you start to think about them. It might have been blind luck that philosophers started thinking about them, rather than images more generally, but once you start down that path, there’s plenty to keep you busy, as Chapters 1–6 make clear. This book doesn’t aspire to diminish interest in pictures, so much as to recast that work within a broader frame. Within that frame, a theory’s quarry can be representations in art, science, and mind. Chapters 7–9 pursue this line of thought.

Most of the theories we will consider in the first five chapters got their start in the middle of the twentieth century. That’s when a number of philosophers with serious interest in the arts encountered the work of a philosophically minded art historian, Ernst Gombrich. In Art and Illusion (1961), he suggests that the history of European art shows us something important about pictures. They involve what can seem like a magical reduction of the many visible aspects of things to the relatively few provided by marks on flat surfaces. Somehow, a flat, uniformly illuminated surface gives the impression of a deep, dappled world. The magic is perceptual: somehow, we experience something more than just a painting when looking at one. And though perception is part of our natural endowment, the magic is highly conventionalized. Standards of convincing rendering shift substantially over time and across cultural space. How should we understand the range of techniques that have evolved for rendering light and shadow, near and far? How have the demands paintings and other images make on perceivers changed over time? What is the “beholder’s share” in our affair with depiction? Following the English painter John Constable, Gombrich cast pictures as experiments about how we see the world (Gombrich 1961: 33–34, 320). These experiments reveal the boundaries of convention: where our habits end and nature beyond our control begins.

So cast, pictures provide philosophical, psychological, and art-historical projects aplenty. What is the relation between seeing things generally and seeing them in pictures? Chapters 1 and 2 investigate theories that focus on this question. Experience theories suggest that pictures evoke distinctive experiences that somehow involve a visual awareness of the objects that are depicted, in addition to awareness of the picture that depicts them. Recognition theories suggest that pictures mobilize the resources we have for recognizing things perceptually. So, when you see a picture of some trees, your ability to recognize trees in the wild is engaged by the picture surface. You recognize both the picture surface, as such, and the trees. Another view in this ballpark, which we will not encounter until Chapter 3, suggests that you experience pictures as resembling what they depict. Pictures are experiments that test the bounds of distinctive experiences, recognition responses, or experienced resemblance. Each view leaves room for convention. What we can experience, or recognize, depends partly on what we have become accustomed to seeing and recognizing. So, while pictures are deeply perceptual, they are also deeply conventional.

Experience, recognition, and experienced resemblance theories might capture what is special about depiction but they fail to engage much with graphs, diagrams, and other images, broadly speaking. They focus on the relation between perceiving things and perceiving pictures of them, with an eye on how conventions wiggle their way into the practice. Graphs and diagrams are not as richly visual as depiction, and they are obviously creatures of convention. They might be closer ken to pictures than languages are, but that doesn’t mean they fit comfortably in the same theory.

Some of Gombrich’s thoughts about pictures apply well beyond depiction. His “Meditations on a Hobby Horse” (1951) casts our representational practices as modes of pretense. Depiction, on this way of thinking, is a process of making effective perceptual substitutes for other things, as follows: we can pretend, when looking at them, that we are looking at what they depict. What counts as a good substitute depends on what we want to do with it, and many other kinds of representation—the images, broadly speaking—can also be modeled as games of make-believe, as we will see in Chapter 4.

Structural accounts, the focus of Chapter 5, look at things quite differently. While most theories focus on responses to representations—experiences, recognition, play—structural accounts ask how such representations relate to one another. The Daumier cartoon that starts us off is a pattern of light and dark on a flat surface. Some aspects of that pattern matter for the cartoon being the cartoon that it is, but some do not. The surface has a color and size, for example, but they seem largely irrelevant to the cartoon. Change them as you like, and the cartoon endures. Change the lines, or the pattern of light and dark, and the cartoon crumbles. We would likely say different things if we were considering color photographs, and scale architectural drawings, whose colors or sizes matter a lot. These are syntactic issues, focused on how a representation’s identity depends on features it has, rather than features it represents. We can ask similar semantic questions about the contents of these representations, as well as questions about how we pair up syntactic features with semantic ones. Gombrich’s presentation of the conventionalized aspects of depiction played a significant role in inspiring structural accounts because they suggest an analogy between pictures and language.

Perhaps the most obvious thing to say about pictures is that they resemble what they depict, while other kinds of representation do not. We can’t blame Gombrich for this one. The resemblance view has ancient roots. Theories in this vein, as Chapter 3 shows, suggest that we can understand what it is for a representation to depict something in terms of properties it shares with its object. In part because of strong criticism by Nelson Goodman (1968, 1972), such theories of depiction were not terribly popular until the 1990s. It will become clear that resemblance views are largely a subspecies of the structural views. They posit a way of pairing syntactic features—features of representations—with semantic features—features the representations are about. This will strike some as odd because the resemblance theory’s fiercest critic, Goodman, was also the most prominent advocate of a structural theory. It happens.

Structural views are not terribly popular within the philosophy of art, even if you count the resemblance theories, but versions of them dominate thinking about representation in the philosophy of science and philosophy of mind, as we will see in Chapters 7 and 8. The reader should know, just so there is no misunderstanding later, that the author of this book is heavily biased in favor of structure. Structure is one key to reorienting the study of pictures, deep and rich as it is, to the study of images, broadly speaking. As mentioned, the main goal is to convince the reader that this broad distinction is worthy of our attention. Another aim, less central, is to suggest a specific account of images, broadly construed: they preserve the structure of what they represent, and in that sense they present things to us. They deliver likenesses, and because of this we can think with them, and thereby learn a lot about what they represent. Even mental images deliver the structure of the world they represent, thus making it available to thought. This is an old thought, recast and reinvigorated. The point of the book is not to establish this claim, so much as to show how it can be derived from a specific approach to images, broadly conceived. Those who find it unpalatable should see the latter part of the book as an invitation to do things differently.

Despite partisan leanings, what follows is a fair and balanced presentation of different accounts of representation, whether they focus narrowly on pictures or more broadly on images. Not all roads lead to structure. Throughout, the presentation resists easy caricatures, with a strong preference for turning over the ground rather than setting things in stone. Neglected papers are put back in play, and some strange bedfellows made. Pictorial realism is rethought in Chapter 6, once all of the accounts of depiction are on the table. It’s a topic that has received a lot of attention lately, so no book on philosophy of images would be complete without it. The problem of photography and object perception does not speak to the present author’s structural ambitions, though it is an absolutely central point of contact between the philosophy of art and the philosophy of mind, and a great note on which to end. The book thus presents a fairly comprehensive, if opinionated, introduction to the philosophy of images.

The following chapters break up into a number of natural, but overlapping, groups. Those who want a critical overview of philosophical accounts of pictorial representation need only consult Chapters 1–5. Each of these chapters more or less stands on its own. The chapters on pretense and structure look well beyond pictures, but they also offer viable accounts of depiction. Add Chapter 6 to that for a discussion of pictorial realism. Realism has been particularly interesting to philosophers insofar as it concerns depiction, not graphs, charts, and the other structure-preserving representations. Chapter 6 mostly stands on its own, too, with the exception being the discussion of “kind realism.” That topic picks up on some themes in Chapter 5, which reappear when we discuss structure-preserving representations in Chapters 7 and 8.

Those with an eye on structure-preserving representation in general can focus on chapters 3–8. Chapter 3 is good preparation for Chapter 5, since resemblance relations are, given Chapter 5’s model, just syntactic–semantic features of representations. The pretense view, unpacked in Chapter 4, applies quite readily to all kinds of representation except mental images, and does an especially nice job of branching out from pictures to diagrams and graphs. Structural accounts, discussed in Chapter 5, are built precisely to deal with many kinds of representation from depiction to written text. Chapters 7 and 8 then show how structure-preserving representation is at the center of some topics in the philosophy of science and philosophy of mind, respectively. As such, these chapters do not stand on their own, but one could get through them with only Chapter 5 as background. Chapter 9 is a natural follow-up to Chapter 8, since both relate philosophy of images to the philosophy of mind. Mental imagery and perceptual content are the themes of Chapter 8, while the highly controversial claim that photographs enable genuine, if indirect perception of their objects is the focus of Chapter 9.

![]()

Plate 2 After Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn, Landscape with three trees (copy), Etching, 21.2x 28.2cm. Courtesy of the Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire. Gift of Bernard A. Kuttner, Class of 1955.

1

EXPERIENCE

Stand in front of the etching and look. You see a planar surface marked with many lines. You also see that it depicts a stand of trees. This is clear to you because, somehow, when looking at this etching you also have an experience as of a group of trees. That’s not to say you have been fooled into thinking there are large plants nearby. You’re content to let the impression remain an impression, shorn of the commitments that usually accompany seeing things. Where are the trees? If forced to choose, you would probably say that the trees look like they recede from and are somehow behind the picture surface. Somehow. After all, the etching is an opaque tangle of lines. How could you see anything back there without moving it out of the way, or walking around it? It is uncontroversial that you see the etching—the gallery is well lit, your eyes are in good shape—but in some other sense you also seem to see the trees. Experiential accounts suggest that pictures are a distinctive kind of representation because of the distinctive experiences they evoke. The trees are there, along with the etching, but in another sense, they are not.

1.1 Experiences and duality

Experiences put us in touch with the world we inhabit. Look, listen, feel, taste, and sniff. The result of doing so is having perceptual experiences: states of you—seeing, hearing, tasting, smelling, feeling—which tell you something about your environment, and even your own body. Though it’s easy to gesture toward experiences, it’s impressively difficult to give an account of them. Four points about experiences are particularly important for what follows.

First, experiences are of objects and their properties. We see, hear, touch, and smell things—this rock, that lamp, that flower—and in doing so we come to know what those things are like: red, bright, loud, fragrant, rough. There is controversy over both the range of properties we perceive and the way we manage to perceive objects.

Second, experiences can be accurate or inaccurate, with respect to both the objects and the properties they are of. The Müller-Lyer lines look as though they have different lengths, but that appearance is misleading. Things seen through tinted glass look oddly colored. The right combination of notes gives the impression of an ever-rising scale. Hallucinations seem to involve objects, like pink elephants, that simply are not...