eBook - ePub

Protecting the Ozone Layer

The United Nations History

- 544 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Protecting the Ozone Layer

The United Nations History

About this book

In the 1970s the world became aware of a huge danger: the destruction of the stratospheric ozone layer by CFCs escaping into the atmosphere, and the damage this could do to human health and the food chain. So great was the threat that by 1987 the UN had succeeded in coordinating an international treaty to phase out emissions; which, over the following 15 years has been implemented. It has been hailed as an outstanding success. It needed the participation of all the parties: governments, industry, scientists, campaigners, NGOs and the media, and is a model for future treaties. This volume provides the authoritative and comprehensive history of the whole process from the earliest warning signs to the present. It is an invaluable record for all those involved and a necessary reference for future negotiations to a wide range of scholars, students and professionals.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Protecting the Ozone Layer by Stephen O Andersen,K Madhava Sarma,Stephen O. Andersen,K.Madhava Sarma in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Ecology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The science of ozone depletion: From theory to certainty*

‘Without a protective ozone layer in the atmosphere, animals and plants could not exist, at least upon land. It is therefore of the greatest importance to understand the processes that regulate the atmosphere’s ozone content.’

The Royal Academy of Sciences, announcing the Nobel Prize for Chemistry, 1995, for Paul Crutzen, Mario Molina and F Sherwood Rowland

‘I wanted to do pure science research related to natural processes and therefore I picked stratospheric ozone as my subject, without the slightest anticipation of what lay ahead.’

Paul Crutzen, Max Planck Institute for Chemistry, Mainz, Germany, 1995

‘Above the Antarctic, the layer of ozone which screens all life on Earth from the harmful effects of the Sun’s ultraviolet radiation is shattered.’

Joseph Farman, British Antarctic Survey, 1987

‘We can now look at the Antarctic ozone hole and know that the ozone layer is not endowed with enormous resiliency, but is instead very fragile.’

F Sherwood Rowland, University of California at Irvine, 1987

‘Stratospheric ozone depletion through catalytic chemistry involving man-made chlorofluorocarbons is an area of focus in the study of geophysics and one of the global environmental issues of the twentieth century.’

Susan Solomon, Aeronomy Laboratory, US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 1999

Introduction

The ozone layer forms a thin shield in the stratosphere, approximately 20–40km above the Earth’s surface, protecting life below from the sun’s ultraviolet (UV) radiation (Box 1.1). It absorbs the lower wavelengths (UV-C) completely and transmits only a small fraction of the middle wavelengths (UV-B). Nearly all of the higher wavelengths (UV-A) are transmitted to the Earth where they cause skin-aging and degrading of outdoor plastics and paint. Of the two types of UV radiation reaching ground level, UV-B is the most harmful to humans and other life forms.

Manufactured chemicals transported by the wind to the stratosphere are broken down by UV-B, releasing chlorine and bromine atoms which destroy ozone. As ozone is depleted, other factors remaining constant, increased transmission of UV-B radiation endangers human health and the environment, for example, by increasing skin cancer and cataracts, weakening human immune systems and damaging crops and natural ecosystems.

Notably, most ozone-depleting substances (ODSs) are also ‘greenhouse gases’ that contribute to climate change, causing sea level rise, intense storms and changes in precipitation and temperature.2

Early Theories: Scientists Identify and Name Ozone

The peculiar odour in the air after a lightning strike had been remarked upon for centuries, including references in The Iliad and The Odyssey, but it was not well understood or named until centuries later. In 1785, Martinus van Marum passed electric sparks through oxygen and noted a peculiar smell; he also found that the resulting gas reacted strongly with mercury. Van Marum and others attributed the odour to the electricity, calling it the ‘electrical odour’.3

In 1840, Swiss chemist Christian Schönbein identified this gas as a component of the lower atmosphere and named it ‘ozone’, from the Greek word ozein, ‘to smell’. He recognized that the odour associated with lightning was ozone, not electricity. He detailed his findings in a letter presented to the Academie des Sciences in Paris entitled, ‘Research on the nature of the odour in certain chemical reactions’. According to Albert Leeds, writing in 1880:4

‘The history of ozone begins with the clear apprehension, in the year 1840, by Schönbein, that in the odour given off in the electrolysis of water, and accompanying discharges of frictional electricity in air, he had to deal with a distinct and important phenomenon. Schönbein’s discovery did not consist in noting the odour… but in first appreciating the importance and true meaning of the phenomenon.’

A few years later, J L Soret of Switzerland identified ozone as an unstable form of oxygen composed of three atoms of oxygen (O3).

Ozone in the Atmosphere

Ozone in the Upper Atmosphere Filters Ultraviolet Light

In 1879, Marie-Alfred Cornú of the École Polytechnique in Paris measured the sun’s spectrum with newly developed techniques for ultraviolet spectroscopy and found that the intensity of the sun’s UV radiation dropped off rapidly at wavelengths below about 300 nanometres5. He demonstrated that the wavelength of the ‘cut-off increased as the sun set and the light passed through more atmosphere on its path to Earth. He correctly determined that the cut-off was the result of a substance in the atmosphere absorbing light at UV wavelengths. A year later, W N Hartley of the Royal College of Science for Ireland in Dublin concluded that this substance was ozone.6 This conclusion was based on his laboratory studies of UV absorption by ozone. Hartley and Cornú attributed the absorption of solar radiation between wavelengths of 200 and 320 nanometres to ozone, and concluded that most of the ozone must be in the upper atmosphere.

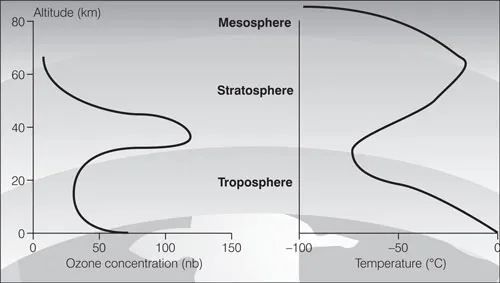

Box 1.1 What is the ozone layer?

Ozone is a molecule made up of three oxygen atoms (O3). Averaged over the entire atmosphere, of every 10 million molecules in the atmosphere, only about three are ozone. About 90 per cent of ozone is found in the stratosphere, between 10 and 50 kilometres above the Earth’s surface. If all of the ozone in the atmosphere were compressed to sea-level pressure, it would constitute a layer only about 3 millimetres (0.1 inches) thick.

Solar radiation at the top of the atmosphere contains radiation of wavelengths shorter than visible light. This radiation, called ultraviolet radiation, is of three ranges. The shortest of these wavelengths, UV-C, is completely blocked from reaching Earth by oxygen and ozone. Wavelengths in the middle range, UV-B, are only partially absorbed by ozone. The higher wavelengths, UV-A, are minimally absorbed and mostly transmitted to the Earth’s surface.

The ozone layer absorbs all but a small fraction of the UV-B radiation from the sun, shielding plants and animals from its harmful effects. Stratospheric ozone depletion: increases skin cancer, cataracts, and blindness; suppresses the human immune system; damages natural ecosystems; changes the climate; and has an adverse effect on plastics.

Note: The thin layer of ozone in the stratosphere is at its thickest at a height of 20–40km. It also accumulates near the ground in the troposphere, where it is a troublesome pollutant.

Source: Ozone Secretariat (2000) Action on Ozone, UNEP, Nairobi, p1.

Figure 1.1 Ozone levels and temperature variation in the atmosphere

In 1917, Alfred Fowler and Robert John Strutt, who became Lord Rayleigh, showed that a number of absorption bands could be observed near the edge of the cut-off in the solar spectrum.7 These were consistent with the ozone absorption bands observed in the laboratory, further proving that ozone is the absorber in the atmosphere. The following year, Strutt attempted to measure the absorption by ozone from a light source located 4 miles across a valley.8 He could detect no absorption and concluded that ‘there must be much more ozone in the upper air than in the lower’, and that absorption does not occur in the lower atmosphere.

Dobson Discovers Day-to-Day and Seasonal Ozone Variations

In 1924, Gordon M B Dobson invented a new spectrophotometer to measure the amount of ozone in the atmosphere. He discovered that there were day-today fluctuations in the ozone amount over Oxford, England, and that there was a regular seasonal variation.9 He hypothesized that these variations in ozone might be related to variations in atmospheric pressure. To test this idea, he had several more spectrophotometers constructed and distributed throughout Europe. These measurements demonstrated regular variations in ozone with the passage of weather systems. One of these spectrophotometers was installed in the town of Arosa in the Swiss Alps, where measurements have been made since 1926.

The Dobson spectrophotometer splits solar radiation into light-wavelengths; because ozone absorbs only some of those wavelengths, the spectrophotometer measures the amount of ozone solar radiation interacts with as it passes through the atmosphere towards the Earth. The amount of ozone measured is expressed in Dobson units, which measure the ozone in a vertical column of the atmosphere. Worldwide, the ozone layer averages approximately 300 Dobson units.

Thomas Midgley Invents CFCs

In 1928, Thomas Midgley Jr, an industrial chemist working at General Motors, invented a chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) as a non-flammable, non-toxic compound to replace the hazardous materials, such as sulphur dioxide and ammonia, then being used in home refrigerators (see Chapter 5). To prove the chemical’s safety for humans, Midgley inhaled the compound and blew out candles with the inhaled vapours. By the 1950s and into the 1960s, CFCs were also used in automobile air conditioners, as propellants in aerosol sprays, in manufacturing plastics and as a solvent for electronic components.

The Ozone Column, the ‘Ozone Layer’ and Natural Balance

In 1929, F W P Götz worked with Dobson’s instrument at Arosa, Switzerland, measuring the ratio of the intensity of two wavelengths at the zenith sky throughout the day. He found that the ratio of the intensities decreased as the sun set, and turned around and increased just as the sun was near the horizon; he named this the Umkehr (turnaround) effect. Thus, he invented the Umkehr method for measuring the vertical distribution of ozone and showed that the concentration of ozone reaches a maximum below an altitude of 25 kilometres.10

The first scientist to identify the ozone ‘layer’ and its full workings was Sydney Chapman, who presented his findings in 1930 in a lecture to the Royal Society of London.11 He developed a photochemical theory of stratospheric ozone formation and destruction, based on the chemistry of pure oxygen. He explained how sunlight could generate ozone by striking molecular oxygen in the atmosphere. Chapman’s findings described the chemistry this way, according to the 1993 book Between Earth and Sky:12

‘When oxygen (O2) in the stratosphere absorbs sunlight waves of less than 2,400 Å (angstroms), the oxygen molecule is split and two oxygen atoms are freed. Like caroming billiard balls, the two oxygen atoms go their separate ways until one free oxygen atom (O) joins a whole oxygen molecule (O2) to create a molecule of triatomic oxygen, or ozone (O3). Ozone (O3), itself being highly unstable, is quickly broken up by longer-wave sunlight of 2,900 Å or by colliding with another free oxygen atom. Thus, ozone molecules are always being made and destroyed at a more or less constant rate, Chapman said, so that a relatively fixed quantity of them are always present… Chapman’s comprehensive description of ozone chemistry, known thereafter as “the Chapman reactions” or “the Chapman mechanism”, proved definitive, and also served to inspire the popular conception of the ozone layer as a vital atmospheric buffer protecting living organisms from deadly shortwave ultraviolet light.’

In 1934, Götz, A R Meetham and Dobson published an interpretation of this phenomenon, pointing out that the shape of the turnaround was dependent on the shape of the altitude profile of the ozone concentration.13 They thus provided experimental confirmation of the basic Chapman theory of ozone formation and loss.

Measurements of emissions of specific spectral lines became possible with the development of high-resolution Dobson spectrometers during the 1940s and 1950s. These instruments were pointed up towards the sky to measure the ‘dayglow’ and ‘nightglow’ of the atmosphere; they measured specific bands of molecules, such as nitric oxide (NO) and hydroxyl (OH). These measurements led to the development of a description of the chemical composition of many of the minor constituents of the atmosphere. In 1950, D R Bates and Marcel Nicolet14 wrote their exposition on the chemistry of the hydrogen oxides in the upper atmosphere; Nicolet later described the details of the expected nitrogen oxide chemistry of the upper atmosphere.15

WMO Global Ozone Observing System

In preparation for the International Geophysical Year in 1957, a worldwide network of stations was developed to measure ozone profiles and the total column abundance of ozone using a standard quantitative procedure pioneered by Dobson. The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) established the framework for ozone-observing projects, related research and publications; this network eventually became the Global Ozone Observing System, with approximately 140 monitoring stations. The British Antarctic Survey and Japanese Scientific Stations in Antarctica in 1957 installed such ozone monitors, which eventually recorded the depletion of the ozone that was later called the Antarctic ozone hole.

Modern Scientists Hypothesize Threats to Ozone

Early Warnings About Damage to the Ozone Layer

Warnings About Supersonic Aircraft

In 1970, Paul Crutzen of The Netherlands demonstrated the importance of catalytic loss of ozone by the reaction of nitrogen oxides, and theorized that chemical processes that affect atmospheric ozone can begin on the surface of the Earth.16 He showed that nitric oxide (NO) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) react in a catalytic cycle that destroys ozone, without being consumed themselves, thus lowering the steady-state amount of ozone. These nitrogen oxides are formed in the atmosphere through chemical reactions involving nitrous oxide (N2O) which originates from microbiological transformations at the ground. Therefore, increasing atmospheric concentration of nitrous oxide that can occur through the use of agricultural fertilizers might lead to reduced ozone levels, he theorized. His hypothesis was that ‘NO and NO2 concentrations have a direct controlling effect on the ozone distributions in a large part of the stratosphere, and consequently on the atmospheric ozone production rates’.

At the same time, James Lovelock of the United Kingdom (UK) developed the electron-capture detector, a device for measuring extremely low organic gas contents in the atmosphere. Using this device in 1971 aboard a research vessel, he measured air samples in the North and South Atlantic. In 1973, he reported that he had detected CFCs in every one of his samples, ‘wherever and whenever they were sought’.17 He concluded that CFC gases had already spread globally throughout the atmosphere.

In another article published in 1970, Halstead Harrison of the Boeing Scientific Research Laboratories in the United States (USA) hypothesized that ‘with added water from the exhausts of projected fleets of stratospheric aircraft, the ozone column may diminish by 3.8 percent, the transmitted solar power increase by 0.07 percent, and the surface temperature rise by 0.04 degrees K in the Northern Hemisphere’.18 He wrote that ‘several authors have expressed concern that exhausts from fleets of stratospheric aircrafts may build up to levels sufficient to perturb weather both ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of plates, figures, tables and boxes

- About the authors

- Foreword by Kofi A Annan

- Preface by Klaus Töpfer

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction and reader’s guide

- 1. The science of ozone depletion: From theory to certainty

- 2. Diplomacy: The beginning, 1974–1987

- 3. Diplomacy: From strength to strength, 1988–1992

- 4. Diplomacy: Racing towards success, 1993–2001

- 5. Technology and business policy

- 6. Implementation of the Montreal Protocol

- 7. Compliance with the Montreal Protocol

- 8. Media coverage of the ozone-layer issue

- 9. Environmental NGOs, the ozone layer and the Montreal Protocol

- 10. Conclusion: A perspective and a caution

- Appendix 1. Ozone layer timelines: 4500 million years ago to present

- Appendix 2. World Plan of Action, April 1977

- Appendix 3. Controlled substances under the Montreal Protocol

- Appendix 4. Control measures of the Montreal Protocol

- Appendix 5. Indicative list of categories of incremental costs

- Appendix 6. Awards for ozone-layer protection: Nobel Prize, United Nations and others

- Appendix 7. Assessment Panels of the Montreal Protocol

- Appendix 8. Core readings on the history of ozone-layer protection

- Appendix 9. Selected ozone websites

- Notes

- List of acronyms and abbreviations

- Glossary

- About the contributors

- Index