1.1 Introduction

Measurement specialists design assessments, gauge reliability, and investigate validity with methods that evolved under trait and behavioral psychology. The language in which the models and procedures are cast reflects this heritage. This language meshes poorly with the language and concepts of an emerging integration of individual, situative, and social perspectives on cognition, which taken together can be called a sociocognitive perspective (Atkinson, Churchill, Nishino, & Okada, 2007). This book argues that models and concepts from the measurement paradigm, appropriately conceived, can nevertheless support the development and use of educational assessments even as they are viewed from a socio-cognitive perspective.1

The project holds some urgency, for a sociocognitive perspective is necessary for progress along several critical assessment fronts. The overarching problem is the growing gap between the understanding of learning and the practices of assessment. One aspect is supporting learning in an increasingly diverse student population. Another is developing and using assessments for different purposes that are both consistent with learning goals and not inconsistent with one another. Yet another is taking leveraging technology to carry out assessment with new forms and purposes, with better adaptation to students and learning opportunities.

The following pages do not resolve all the challenges assessment faces. They do, however, offer a way of thinking about educational measurement that helps bring forth some of the advances we seek. The required reconception of just what, if anything, is being measured, even just what measurement means, discourages some familiar practices and opens the door to new ones. A reconception of measurement modeling can improve the usefulness and validity of educational assessment in practice.

A bit more should be said up front about what “measurement” will be taken to mean, as this is a matter of some debate in educational and psychological testing. Sketches of three views that Markus and Borsboom (2013) described suffice for now. They cite Michell (1997) for a classical theory of measurement, as “the estimation or discovery of the ratio of some magnitude of a quantitative attribute to a unit of the same attribute” (p. 358). The degree to which educational assessment data and models can meet its demanding requirements is an often-disregarded empirical challenge, which Chapter 13 discusses more fully in connection with item response theory. An operationalist view defines measurement as “the assignment of numerals to objects or events according to rules” (Stevens, 1946, p. 677). This view does include the models we will address, but it includes almost anything. It permits any assignment scheme of numbers to the results from any procedure, to be followed by an attempt to figure out “what level of measurement” has been achieved.

The scope of our discussion is best captured by Markus and Borsboom’s third view, midway between the classical and operationalist views. In latent-variable modeling views of measurement,2 a structure is posited with unobservable variables for persons which, through a mathematical model, give probability distributions for observable variables. This view includes the models of classical and modern psychometrics, which have proven value for guiding assessment design and reasoning from assessment data (Mislevy, 1994). But how should we think about these models, use them, and extend them, when our understanding of human learning has transformed from the psychological views that produced them?

What we need is an articulation between, on one hand, these coarser grained, between-person measurement models for patterns in behaviors that are at an appropriate level for many practical educational problems, and on the other hand, the more recent finer grained, within-person models for the genesis of those behaviors. Such an approach would take up a challenge that Richard Snow and David Lohman (1989) laid down in the third edition of Educational Measurement (Linn, 1989):

Summary test scores, and factors based on them, have often been thought of as “signs” indicating the presence of underlying, latent traits…. An alternative interpretation of test scores as samples of cognitive processes and contents, and of correlations as indicating the similarity or overlap of this sampling, is equally justifiable and could be theoretically more useful. The evidence from cognitive psychology suggests that test performances are comprised of complex assemblies of component information-processing actions that are adapted to task requirements during performance.

(p. 317) 3

Research in domains related to a sociocognitive perspective and in assessment itself enables us to make real progress on such a project. Snow’s own contributions to working out an articulation appear in Remaking the Concept of Aptitude: Extending the Legacy of Richard E. Snow (Corno et al., 2002). Both the National Research Council’s “Foundations of Assessment” Committee (Pellegrino, Chudowsky, & Glaser, 2001) and Spencer Foundation’s “Idea of Testing” project (Moss, Pullin, Haertel, Gee, & Young, 2008) brought together experts from various fields to similar ends, the former from an information-processing bent and the latter with a sociocultural lens. We will build on these projects, studies of learning, experience in subject areas, and developments in assessment itself.

1.2 LCS Patterns Across People and Resources Within People

In assessment, we observe an examinee acting in particular situations. We interpret the situations and actions in social context, and we draw inferences about the person as they might be relevant to other situations. To better understand what the examinee is doing and what we are doing when we reason this way, it helps to identify three layers of things that are happening.

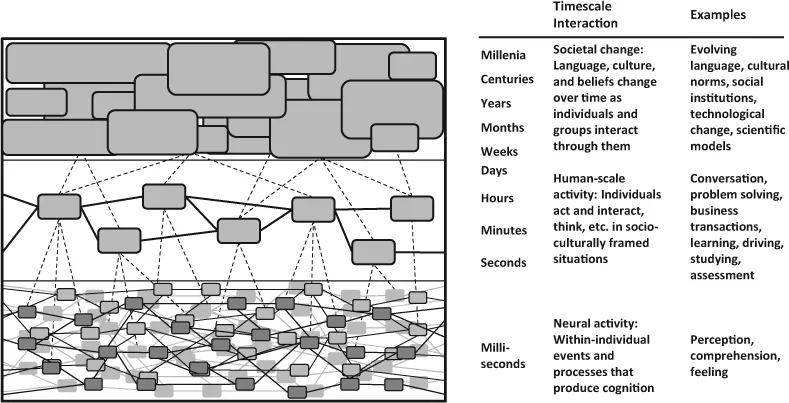

Figure 1.1 depicts the levels of phenomena and associated timescales we will address (Lemke, 1997, 2000). The middle layer represents the actions, events, and thoughts we experience as individuals. The philosopher Daniel Dennett (1969) called this “personal-level” activity: acting within situations as we are aware of them, as we experience them, as we consciously understand them, as we interact with the world and with each other; thinking, planning, conversing, reading, working, playing, solving problems, using representations; cooperating or competing with family, friends, co-workers, and countless others we do not know personally.

Personal-level activity is mediated by the extrapersonal, or across-persons, patterns suggested in the top panel. These are regularities in the interactions of people in their overlapping identities and communities, and it is through them that our actions constitute meaningful activities (Engeström, 1987; Sperber, 1996; Wertsch, 1994). They emerge from the interactions of individuals in societies. There are widely shared ways of thinking and interacting, such as what it means in a culture to be sick or to be married. There are activity patterns, some broad and others detailed, some rigid and others flexible, that shape our interactions in classrooms, grocery stores, and visits to relatives. There are narrative themes, from common storylines in human interactions to highly structured scientific models. There are fine-grained patterns such as the grammars and constructions in a language and in arithmetic schemas like “Change” and “Compare.”

Figure 1.1 Levels and timescales in human activity.

I will use the broad term “linguistic, cultural, and substantive patterns” (LCS patterns) to encompass these ways of thinking and acting, including tools and representations. At times we will call attention to aspects of what some activity is about, the forms people use, and what they do (i.e., themes, semiotic systems, and patterns of activity implicated in LCS patterns). Every meaningful action involves all of them. These are what the shapes at the top of Figure 1.1 represent: patterns that have emerged across people, which structure the unique instances of person-level activity depicted in the middle. We can see elements of thematic patterns, semiotic systems, and activity structures re-combining in characteristic ways across different situations.

We can see similarities, as well as systematic differences, in how we use language in a conversation with a friend and in an oral proficiency interview (Johnson & Tyler, 1998), or what we do when we practice guitar alone, jam with friends, and play in a band for a dance. LCS patterns are not independently existing entities in themselves, but regularities in the myriad interactions among individuals. As such they mediate both interactions among people and thinking within people, and the complicated chains back and forth between the two (Sperber, 1996). LCS patterns can vary over time and over place as people use them, and they have varying degrees of stability. The “English language,” for example, actually varies from speaker to speaker, place to place, topic to topic, and situation to situation (Young, 1999). Yet there are enough regularities, reinforced in everyday use, written materials, and institutional practices, that with a little effort we can read a play Shakespeare wrote 400 years ago.

Communities exhibit identifiable, recurring, configurations of themes, structures, and activities, called practices—from playing games to writing grant proposals. Lave and Wenger (1991) described how we learn practices in communities by participating in activities with other members, peripherally at first, and extending our capabilities as we become more experienced. Many, such as our first language and social patterns, we learn without formal training. Others require intentional effort and focused attention, often over extended periods of time. Herb Simon called attention to the concepts, tools, terminology, and representational forms in the “semantically rich domains” that are the focus of formal instruction and assessment (Bhaskar & Simon, 1977). Examples are the structures and practices of a second language (Young, 2009), procedures for subtracting mixed numbers (Tatsuoka, 1983), scientific models for thinking about objects and motion (diSessa, 1988), and strategies for troubleshooting aircraft hydraulics systems or computer networks (Steinberg & Gitomer, 1996; Williamson et al., 2004).

The bottom panel of Figure 1.1 represents within-person, non-conscious, processes that give rise to an individual’s actions—sub-personal phenomena, to borrow another term from Dennett. In order to produce meaningful human-level activity, the patterns of neural activity within individuals must both relate to LCS patterns and adapt to the particulars of the unique situation at hand. Young (2009) uses the term “resources” to refer to a person’s capabilities to assemble particular patterns to understand, create, and act in language use situations. The idea applies to knowledge structures and activity systems more broadly, as for example when we talk, think, and do science (diSessa, 1988; Dunbar, 1995; Hammer, Elby, Scherr, & Redish, 2005) or when we play video games, talk with our friends about them, and read cheat sheets (Gee, 2007; Shaffer, 2007). As Greeno, Smith, and Moore (1993) put it, “Learning occurs as people engage in activities, and the meanings and significance of objects and information in the situation derive from their roles in the activities that people are engaged in” (p. 100). In this way we become attuned to LCS patterns, their affordances and constraints, their conditions of use, and how people use them to accomplish things in the physical and social world. LCS patterns are emergent similarities across the resources individuals develop, in the continual interplay between the social and the cognitive in the flux of personal-level activity.

We are aware of aspects of some of our own resources and some of the LCS patterns we think and act through. Indeed, metacognitive skills are resources we develop for managing and extending our cognitive resources. But we are not aware of the underlying processes by which we develop or activate resources.

Assessment is observing a person acting in a handful of particular situations, interpreting the situations and actions through the lenses of particular practices or LCS patterns, and making inferences about the person’s capabilities for acting or learning in other situations in which the targeted patterns are relevant.4 We want to understand assessment in terms of the interplay among the three levels of Figure 1.1: (1) extrapersonal LCS patterns in the top panel, which are targets of the assessm...