- 292 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

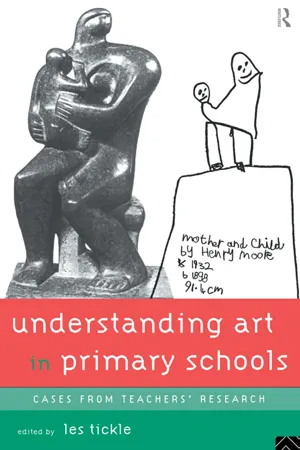

Understanding Art in Primary Schools

About this book

Even the youngest children in primary schools are now required not only to make art, but also to study it, developing an understanding of the huge variety of art and craft from different times and places. But how do teachers actually tackle this, when most have not studied art themselves?

This collection brings together case studies to show how a variety of teachers have used one particular art collection as a focus for practical art. Throughout, the voices of the children involved show us how they react to their encounters with art objects. This wealth of first hand evidence and practical experience will benefit all teachers.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Understanding Art in Primary Schools by Les Tickle in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education GeneralChapter 1

Visual art and teacher research in primary schools

The cases which are included in this book are from primary school teachers who responded to the challenges of the revised art curriculum. Each is characterised by three main aims: to develop the teachers’ knowledge of art; to devise teaching strategies for their pupils which will help them effect the art curriculum requirements; and to research their teaching and the pupils’ responses to it. Few of the teachers have an art background from school or from their teacher education courses. They responded to the new demands of the art curriculum by engaging in this triple approach to their own professional development, as part of a programme intended to bring them and their pupils into direct and prolonged contact with works of art.

Since 1993, Sedgwick, an international insurance broking and financial services group with a commitment to working in and with the community for the promotion of both education and the arts, has provided scholarships for primary school teachers to develop their knowledge and their teaching of the visual arts, with special reference to the Sainsbury Collection housed at the University of East Anglia, Norwich. It is an extensive and diverse collection of art, containing objects from many cultures and periods of time. The partnership between the commercial sector, schools, and the University has enabled the teachers to make a substantial response to the teaching of art in the national curriculum; a response which has also given them access to the expertise of art historians, anthropologists, archaeologists, artists, and art educators based in the University.

Their development of subject knowledge, use of new teaching strategies, and induction into teacher research, is usually accompanied by testimonies of excitement at the prospects, for themselves and for their pupils, of learning more about art. There is often some associated trepidation about entering the unfamiliar territory of the visual arts and of teacher research. What characterises their endeavours most notably is the commitment, determination, and willpower to improve the art experiences of both their current and future pupils. Achieving the greatest possible efficacy in the induction of every pupil, whatever the child’s background, disposition and capabilities, is the main driving force. They also share a willingness to provide collaborative leadership, to share their work with other teachers.

Different aspects of knowledge and practice are deliberately sequenced in the programme they follow, at least in the emphasis given to each:

• Developing personal familiarity with art objects, and strategies for studying them, and with the lives of artists and the cultures in which art objects were created;

• Devising teaching aims and plans for pupils’ projects, including preparatory work in schools; visit(s) to the gallery; and follow-up work by pupils;

• Deciding a research focus and strategy, in relation to the teaching aims and plans, and gathering data, recording and storing the evidence, and analysing and organising it into report form;

• Sharing the research and the issues it generated, among each other, with their colleagues in school, and with teachers from other schools.

Improving personal artistic knowledge and attitudes, devising art teaching projects for pupils, undertaking research into the conduct of teaching and pupils’ learning, and disseminating the research, tends to happen without a neat sequence, however. From the beginning, seeking to develop some understanding and practice of educational action research is part of the learning. Thinking about what teacher research implies, and about what to research and how to do it, is a long and deliberative venture, and the seeds of thought are sown early. Equally, gaining knowledge and understanding of art continues throughout the programme, as experience in handling information about objects and artists and cultures, and experience in observing and responding to the art objects, is pursued and deepened. The focus on the potentials for pupils is a permanent and paramount concern. What might a possible project focus for pupils be? How could it be fitted into the topic for the Spring term? Which objects, artists and cultures have the greatest potential for engaging the interests of pupils? Do I know enough about this artist or that culture to enliven the pupils’ learning? How will 4 year olds respond to visiting an art gallery? Will they be able to reach up to see the objects?

These kinds of self-searching, practical and thought-provoking questions show that this is new ground being broken. They are interspersed with questions about the meaning of action research in this type of curriculum development. What kinds of data might be useful? What are data? Where will I find them? How should I record them? Is the research topic too broad or too narrow, and how much evidence is needed to help to understand children’s learning?

A central assumption of action research is that curriculum proposals and teaching practices are to be treated as problematic, as provisional, and worth testing through the collection of evidence. Its basic tenet is that teachers, seeking to extend practical knowledge and experience, constantly test out ideas. Ideas are changed according to circumstance and rethinking, which is based on experience and the analysis of evidence. These new ideas are assimilated into a repertoire of practice. A commitment to systematic questioning of teaching is characteristic of a disposition to seek an understanding of events through the mastery of investigative skills. The development of practice, it is presumed, will be most effective if it is based on the capacity to make sound judgements. In turn, such prudence will result from careful handling of evidence of professional action.

Professional development based on such assumptions involves teachers in identifying the developmental needs of themselves and their institutions, and working out their own strategies towards meeting those needs, perhaps with external support. The emphasis is on a sharing of interpretations and understanding of practical curricular concerns, and a sharing of expertise to arrive at solutions for teaching. Action research is often described and defined in the form of ‘models’ in which action is taken, a problem is identified, data relating to the problem are sought and analysed, actions are amended, and further evidence is sought (Elliott 1991; Hopkins 1985; Kemmis and McTaggart 1982; McKernan 1991; Winter 1989).

The motivation for carrying out action research is often a concern to improve one’s practice. It is just as likely to serve teachers when changes are initiated by externally generated events, as in the cases reported later, where the need to work out one’s aims and to test if they are being realised has been brought about by recent developments in the curriculum. The association of action research with ‘reflective practice’ is commonplace, and the work of Donald Schon (1971, 1983, 1987) has been influential in that the rhetoric of his ‘reflective practitioner’ has become widespread among professionals. The teachers who have written chapters in this book certainly felt a need to achieve a mastery of practice. They were in a position to initiate change in their own work, since the new requirements of the curriculum were not yet tried and tested. Their precondition for enquiry and extensive reflection was the formulation of teaching aims and the testing of practical strategies to enhance their pupils’ experiences of the visual arts. The data from these teachers show that sense of inquiry and reflective thought, which pervaded their introduction of the new requirements of the art curriculum. The concern to learn from such inquiry, and to develop particular aspects of professional knowledge and practice, is very evident in their work.

However, they do not necessarily follow the procedures of ‘models’ of action research. Their thinking is sometimes nearer to Schon’s view of reflective practice in which reflection-in-action is conducted on the spot, triggered by practical problems and immediately linked to action. Reflection-on-action is less immediate but none the less based in practice. An example of this which these teachers reported was their initial experience of guiding a large number of young children on their first ever visit to an art gallery. Anticipation, careful planning, speculation, prediction, concern about social behaviour, and hopes about effective learning experiences were just some of the characteristics and uncertainties associated with the event. The search for evidence of pupils’ responses to instructions and tasks was a high priority from the moment of arrival. Would they wander off? How long would they sustain concentration? Were there too many distractions to focus on selected objects? and so on. Readiness to act decisively in response to emerging evidence, in order to make the most of the opportunities presented, was reported widely.

There were also many immediate and spontaneous judgements to be made about how visual art projects should or could be developed in the classroom, and how school-based activities might relate to gallery visits and contact with works of art. From among these, each of the teachers chose a focus for more prolonged gathering of evidence, which formed the basis of the reports, guided by principles of action research which are included in Understanding Design and Technology in Primary Schools (Tickle 1996).

This meeting of innovations provides a story of not only commitment, anguish, energy, and willpower but also domestic disputes apparently! Surprise, enlightenment, confession, and other human characteristics and experiences are never far below the surface when the complexities of learning subject knowledge, teaching strategies and research methods are combined. But it is the knowledge of art, the development of teaching, and the analyses of their pupils’ responses to the innovations which are the focus of each of the teacher research chapters of the book. The book is intended to serve the needs of other primary school teachers in two ways:

• By representing approaches to teaching the dimension of knowledge and understanding in primary art education;

• By providing examples of research undertaken by teachers in relation to their own developing understanding of art, teaching projects devised by them, and their own learning from researching children’s responses to their teaching.

Chapter two outlines the new curriculum for primary art, and addresses what I consider to be a central and abiding problem, intrinsic to art activity and now faced by all teachers and pupils. It is the relationship between making one’s art and the study of others’ art. This is an interesting puzzle, which I tackle first from the point of view of the study of art. The book emphasises that dimension of the curriculum, to redress the balance from an emphasis on making art (both in school practice and in books available on teaching art). This should not be taken to imply that the study of art should come before making it. How artists relate the study of art to their making of it, how the two activities relate, is not clear cut. Understanding the process itself might lead to ‘authentic’ knowledge of art in classrooms. That might help to generate authentic making of art, rather than pastiche and the mimicry of techniques of other artists which seems commonplace. Those issues are part of what the later chapters explore.

Chapter three describes some research endeavours which have sought to know just how children respond to works of art. The research is both recent and fickle, the main message being an invitation to construct descriptions of teaching aims and instructional strategies, particular learning contexts, and case studies of children learning in their various circumstances. This is an appeal to test out curriculum practice. For teachers it amounts to an appeal to create their own curriculum projects, to monitor them, and to make them available for others to draw upon, emulate, amend, or vary from, in the best traditions of research.

The teachers’ chapters are centred around art objects in the Robert and Lisa Sainsbury Collection. The collection holds art from all over the world, and from ancient times to the present day. It contains the work of some twentieth century European artists, such as Henry Moore, Pablo Picasso, and Hans Coper, and the kinds of art from other cultures in which they were interested. Ancient Mesoamerican (Olmec, Mayan, Aztec) sculptures, African carved heads, figurines from the Greek Cyclades Islands, are just a few sections of the collection. There are other contemporary artists represented in the collection for whom such influences are not so evident: Francis Bacon, Alberto Giacomet...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of plates

- List of figures and table

- List of contributors

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Visual art and teacher research in primary schools

- 2 Art, art education, and the twenty-first century

- 3 Children’s responses to art

- 4 Room for improvement

- 5 Representation, emotion, and special educational needs

- 6 More than Moore

- 7 Facing feelings

- 8 Reception for a wolf and a little dancer

- 9 Looking at faces

- 10 First responses to sculpture

- 11 Art and communication

- 12 Art is … extending the perceptions of art with six year olds

- 13 Understanding sculptors and sculpting

- 14 American North West Coast art, story, and computer animation

- 15 In search of Mundesley totems

- Index