![]()

Chapter 1

The law of evidence: An introduction

LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

•Identify the basic rules of evidence law and understand how they have developed

•Critically analyse the different categories of evidence and their purpose

•Determine when and the reason why certain evidence is admissible

•Explore the rules for the exclusion of evidence

•Outline the different roles that lawyers, judges and juries play in evidence law

INTRODUCTION: WHAT IS EVIDENCE LAW?

The law of evidence is often described as a library or set of rules and exceptions that come together to help the judge and jury recreate, in their minds, what allegedly happened within a given situation. These rules govern what evidence can be put before the court (what is admissible and what may be excluded), how it should be presented at court and how facts are proven in court. Evidence can be defined as facts or information that indicates if a proposition is legally acceptable as being true or valid, for example the results of an alcohol blood concentration report as evidence that the accused was over the permitted legal limit while driving.

The parties to an action (whether that is the accused or the claimant/defendant) do not have automatic permission to present to the court everything that may assist their case. Parties may only present evidence to the court that is (a) relevant to a disputed fact and (b) admissible. Even if this rule is satisfied, a judge may for a number of reasons decide to exclude it.

In this chapter we will examine these rules and exceptions and consider how the law has developed as it has and why judges still retain the discretion to exclude evidence. We will also look at the different categories of evidence and then consider the roles of key legal professionals with respect to the law of evidence in England and Wales.

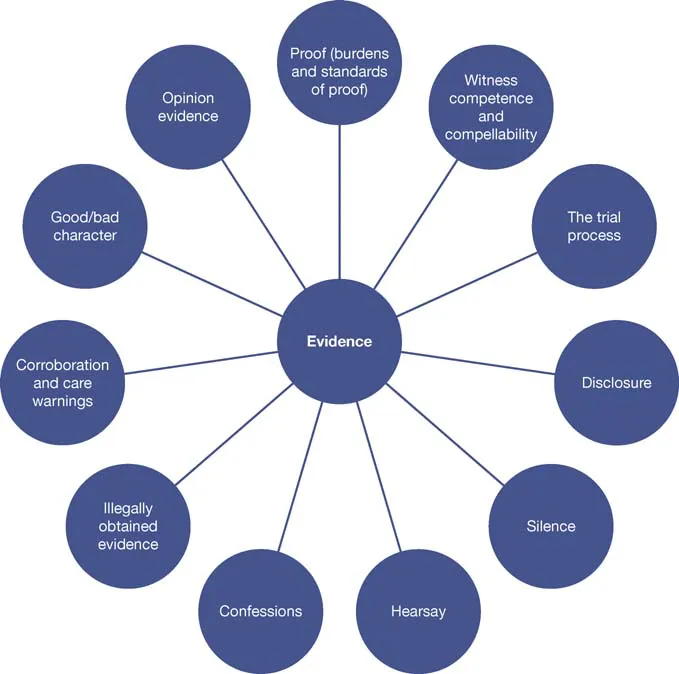

Figure 1.1 highlights the major types of evidence law you are likely to encounter on your own course, and which we will go on to examine in this book. The definitions that are used in the book are consistent with those you will encounter on your own course and will remain consistent throughout the book.

Figure 1.1 Evidence types

AN EXCLUSIONARY APPROACH BY THE ENGLISH COURTS

In this chapter we will look at how and why the law of evidence has developed as it has in order to understand the context of the current law.

There are many jurisdictions in which all relevant evidence is admissible. In contrast, the position in the English law of evidence is far more cautious. This cautious approach was heavily criticised because it would often result in relevant evidence being excluded. The origins of this approach lie in the concept of trial by jury and the notion that:

(a)jurors were unable to analyse all the evidence that they were presented with;

(b)they may assess it inappropriately by giving it more weight than it deserved; or

(c)they may be far more easily prejudiced by it if it were not excluded (public policy/fairness).

English trial judges were also especially vigilant in excluding evidence they believed to be concocted, distorted or fabricated. There were also public policy reasons for the exclusion of evidence from disclosure, such as legal professional privilege and public interest immunity, examples of which are discussed later in the book. Hearsay evidence was also commonly excluded – as discussed in Chapter 7.

The current approach is an inclusionary one. For example, for the first time recent legislation such as the CJA 2003 statutorily provides for the inclusion of hearsay and bad character evidence, albeit subject to a number of safeguards. It is important to note that such evidence was admissible in certain circumstances and under particular conditions prior to this. These changes are based on a combination of logic and policy, for instance a change in the perception relating to a jury’s ability to assess bad character evidence.

LAWYERS AND EVIDENCE

In England and Wales lawyers (barristers/solicitors) are instructed to act for the accused and present the evidence on an adversarial basis, which is in opposition to the evidence of the Crown Prosecution Service, to a judge and jury. In contrast, the continental system is inquisitorial where the judge acts to supervise the gathering of evidence and thus plays a far more active role in the resolution of the case.

Lawyers play a key role in preparing and presenting their client’s case. When assessing the evidence the lawyer will normally ask himself or herself the following:

This is because only relevant and admissible evidence can be presented to the court. You will use the same test yourself when considering a problem question or assessment on your course.

Logically, relevance is considered first. If you are presented with ten pieces of admissible evidence, it may be that only five are relevant to the case at hand. We will see that even where five pieces of evidence are considered relevant, not all of these may be admissible; one of the reasons for this may be that the evidence was improperly obtained. For instance the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE) and the PACE Codes of Practice (COP) provide a framework in relation to police powers and safeguards. The COP cover stop and search, detention and arrest, investigation and identification, and interviewing of suspects. A breach of the Codes is likely to result in evidence, although relevant and admissible, being excluded. For example the reliability of a confession will be called into question if the police fail to allow a suspect to have sufficient rest before, and during, an interview (see R v Fulling 1987 2 All ER 65). This will potentially breach the code of practice that relates to detention.

Figure 1.2 Questions when assessing evidence

It is a fundamental rule of the English law of evidence that any relevant evidence that is rendered inadmissible cannot subsequently be presented to the court for consideration. This strictly applies even for evidence that might be central to a case.

CATEGORIES OF JUDICIAL EVIDENCE

Before looking at the different types of evidence, it is important to understand that a single piece of evidence can be admissible as proof of numerous things. For instance the contents of a letter will be categorised as hearsay if presented as proving the truth of its contents – perhaps it contained a threat. If the contents are inadmissible, because they do not fall into any of the categories of admissible hearsay by reason of the CJA 2003, then that same letter will not be hearsay if it is presented to contradict a defendant’s claim that no communication had ever occurred between his or herself and another party to the proceedings. Therefore, students are required to have a working knowledge of how various rules apply to the same piece of evidence in a single scenario – this is discussed where relevant.

In this book, we will consider the following categories of evidence:

•Direct and circumstantial

•Original, primary and secondary

•Presumptive and conclusive

•Oral testimony

•Real and documentary

Direct and circumstantial evidence

Direct evidence does not require any further inferences to be drawn from it and usually concerns a direct perception of a fact either by sight, sound or even smell or taste. For example, if Mark saw Sian stabbing Julie with a knife, then providing the jury believed Mark, this would be direct evidence that Sian stabbed Julie.

In contrast, circumstantial evidence does require further inferences to be drawn. For 1 instance, Peter’s testimony that when he arrived at the scene of the crime Frank was standing over Mabel’s body holding a bloodstained knife is circumstantial evidence of the fact that Frank killed Mabel because he cannot give direct evidence of this as he had not actually seen Frank stab Mabel. The inference that will be drawn is often obvious but occasionally it is not. In such a situation, other additional circumstantial evidence can be used to support the inference. For example, in the scenario above, Peter may have heard shouting and then a scream before he arrived at the scene, which may suggest that Frank had no time to flee.

When considering whether circumstantial evidence proves something or not the jury will ask itself the following questions:

(a)Does this evidence prove the relevant facts or at least some of them? If the answer to this is yes, then it will ask itself:

(b)Should the fact in issue be inferred by the existence of these relevant facts?

Other circumstantial evidence may also assist the jury in drawing an inference; Frank may have had no answer to why he was standing at the scene of...