![]()

1

Data collection and

hypothesis testing

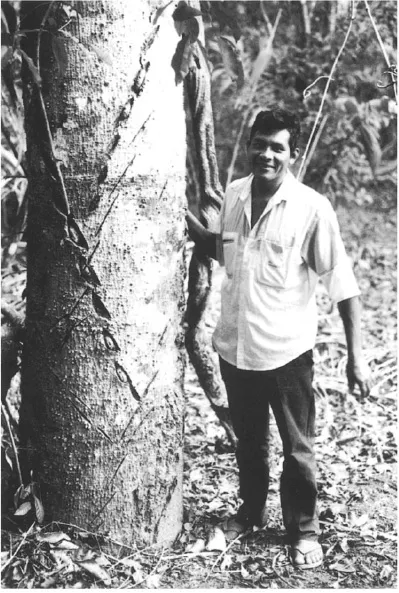

Figure 1.1 German Cayti, from the Chimane indigenous community of Puerto Mendez, Bolivia, showing scarring on the bark of Hura crepitans (Euphorbiaceae), which is used as a fish poison. Local people can provide a vast amount of data on local plant resources.

1.1 Choosing an approach

When designing an ethnobotanical project, it is important to define what you wish to achieve and then to select the approach which best suits your interests, budget and schedule. It is easy to be overly enthusiastic about what can be accomplished in a short field season. Once the project begins, you discover the complexity of local ecological knowledge and the diversity of the flora and fauna. You experience unforseen delays caused by the weather, equipment failure and other events beyond your control.

Many of the methods used in ethnobotanical studies are time-consuming and moderately costly, making it impractical to apply all in a single period of fieldwork. For this reason many researchers divide their time between visits to the field with stays back home analyzing the data and writing up the results. Once you complete the process of adapting a technique for your field site, collecting the data and analyzing the results, you will be better able to choose a complementary approach in the future. For example, if you record the uses and names of medicinal plants in a community, you can identify the specimens and search ethnopharmacology databases and literature to evaluate which merit further study before returning to the field to gather samples for chemical analysis.

It may be costly to make several trips to the field, but remember that the most satisfactory projects – from a personal viewpoint as well as from the perspective of the community and your colleagues – are those which span several seasons and continue for a number of years.

In practice, the time and resources that ethnobotanists can dedicate to projects vary widely. Let's take the example of several case studies discussed in this manual:

• K.C. Malhotra, M. Poffenberger, A. Bhattacharya and D. Dev spent two days making a rapid inventory of non-wood forest products and an assessment of forest regeneration in a village in West Midnapore District in Southwest Bengal. This formed part of a long-term study of the impact of Forest Protection Committees on forest regeneration in the region [1].

• O. Phillips spent a total of 12 months over a period of five years in the Tambopata Reserve in southern Peru to document Mestizo use of plant resources [2–44].

• R. O. Guerrero and I. Robledo, combining work in the field and the laboratory, analyzed the biological activity of plants from the Caribbean National Forest over a period of 30 months [5].

• B. Berlin worked with various colleagues in Chiapas, Mexico, for several years in the early 1960s to document the botanical classification of the Tzeltal, a group of Maya-speaking agriculturalists. Berlin returned to the region in the late 1980s with other colleagues to focus on the medical ethnobiology of the highland Maya in a multi-year project [6, 7].

1.2 Six disciplines which contribute to an ethnobotanical study

Because it is often said that ethnobotany is a multidisciplinary endeavor, it should be easy to enumerate the fields of study that contribute to analyzing how humans interact with the plant world. What are they? This is a question often posed by people who are beginning their first ethnobotanical study. Yet even experienced researchers fumble about for the recipe: botany of course and some linguistics, a background in anthropology helps and you had better know some chemistry and economics.

The response depends in part on the kind of project that is planned. There are four major interrelated endeavors in ethnobotany: (1) basic documentation of traditional botanical knowledge; (2) quantitative evaluation of the use and management of botanical resources; (3) experimental assessment of the benefits derived from plants, both for subsistence and for commercial ends; and (4) applied projects that seek to maximize the value that local people attain from their ecological knowledge and resources. Walter Lewis, an ethnobotanist at Washington University, has suggested that the first three elements be referred to as basic, quantitative and experimental ethnobotany, respectively [8].

The focus in this manual is on six fields of study: botany, ethnopharmacology, anthropology, ecology, economics and linguistics. In any long-term project, techniques borrowed from these fields can be combined to carry out a systematic survey of the traditional botanical knowledge in a single community or region.

1.3 Rapid ethnobotanical appraisal

Although many researchers prefer long-term projects, they are sometimes called upon to make a rapid ethnobotanical study – gathering data on minor forest products for an environmental impact statement, making a preliminary list of biological resources at sites that have been set aside as protected areas or simply conducting an initial ethnobotanical inventory in several communities in order to decide where it would be most interesting to carry out long-term research.

We can find many faults with studies that only last a few days. They do not allow a deep working relationship to develop between an ethnobotanist and the community. Careful documentation of the cultural and biological aspects of local knowledge is not possible, because there is little time to make voucher collections, transcribe local names or talk with a range of informants. Above all, short visits do not permit local people to learn rigorous ethnobotanical methods that would allow them to manage more effectively resources in their own communities. Yet the urgency of encountering solutions to community and conservation problems sometimes requires that we make a quick assessment of ecological knowledge and resource use, while rapidly teaching local people some of the basic techniques we employ.

As a response to this dilemma, international development workers have improvised various methods of making a fast low-cost assessment of the use of forest resources and many other aspects of community development. Techniques adopted from various disciplines have been combined to form a collaborative approach called Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA). Although originally developed to guide and evaluate development initiatives, PRA is readily applicable to ethnobotanical studies, as can be seen from the example given in Box 1.1.

Box 1.1 Rapid appraisal of non-wood forest products in India

Over a two-day period in 1991, a multidisciplinary team carried out a rapid appraisal of forest regeneration and harvesting of non-wood forest products with the members of a community in West Midnapore District in Southwest Bengal. As a first step, the participants selected several 100 m2 plots that showed various degrees of protection from deforestation. They made an inventory of the trees in each plot, determining the species and recording the size of each individual.

In a working paper, K.C. Malhotra, M. Poffenberger, A. Bhattacharya and D. Dev [1] describe the ethnobotanical component of this experience:

... tribal and some non-tribal people who have strong ties to the forest can identify hundreds of productive species and how they are used as sources of foods, medicines, fiber and construction materials, gums, dyes, tannins, etc. Using secondary data and local resource persons this information was documented in the case study sites. Listings were made for all products used for home consumption or sale. Data were collected regarding harvesting seasons and volumes. An attempt was also made to determine the parts of the plant utilized.

During this rapid appraisal, many useful plant species were identified. For example, the researchers recorded the names of 29 minor forest products available in a forest that had been protected for three years. The Latin names of 15 of these were noted and information on the market price was recorded for six of them.

In their report, the coordinators of this participatory exercise also point out the limitations of their assessment. They were not able to document all of the important biological resources, neglecting for example the mushrooms that are available only during the monsoon and early post-monsoon periods. They did not enquire in a systematic way about the volume of plant materials harvested or what prices they brought in local markets. No ethnobotanical voucher collections were made and the scientific names of nearly half of the plants went undetermined.

Judging the successes and deficiencies of the experience, they made suggestions on how future research should proceed. Among other recommendations, they proposed that the exercise be extended to include visits during the various seasons of the year and that an intensive study be made of the marketing of non-wood resources, including collection of data on volume flows and the possible depletion of certain plants.

Although PRA borrows many of its tools from traditional disciplines such as rural sociology, anthropology, ecology and economics, there are important differences that distinguish this rapid approach from academic research. Local people are full participants in the study rather than being merely the objects of the investigation. They take part in the design of the study, data collection, analysis of the findings and discussions of how the results can be applied for the benefit of the community. The outsiders in the research team come from a variety of academic backgrounds, ensuring a multidisciplinary perspective. The relationship between all participants – locals and outsiders – is egalitarian, avoiding the hierarchical or top-down approach common to much research.

The techniques can be carried out in a short time and do not require expensive tools because participants are seeking a sketch of local conditions rather than an in-depth study. A small group of local people is selected to be interviewed in a semi-structured way. A wide range of topics may be covered in a preliminary way, allowing a comprehensive view of how the community works as a whole. Measurements are qualitative rather than quantitative and few statistical tools are used in the interpretation of the results. The emphasis is on highly visual techniques that community members carry out amongst themselves, often in collaboration with outside researchers – sketching maps to show local classification of ecological zones, creating pie charts that represent the amount of time that people dedicate to various productive activities or drawing calendars which show seasonal fluctuations in climate, to give just a few examples. The analysis of the data is carried out in the community, which allows participants to modify their meth...