- 136 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Alternative Geographies

About this book

An accessible and groundbreaking text that takes a fresh view of contemporary geographical issues by looking at the geographies we have lost.

Geography means writing about the world. Alternative ways of writing about the world are introduced and critically evaluated. The book discusses medieval cosmologies, Renaissance magic, feng shui, and the knowledge systems of indigenous people. Alternative Geographies provides an alternative way of looking, describing and understanding the world

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

From Cosmography to Geography

Are not the mountains, waves and skies, a part

Of me and of my soul, as I of them?

Is not the love of these deep in my heart

With a pure passion? should I not contemn

All objects, if compared with these? and stem

A tide of suffering, rather than forgo

Such feelings for the hard and worldly phlegm

Of those whose eyes are only turn’d below,

Gazing upon the ground, with thoughts which dare not glow?

- Lord Byron, Cbilde Harold’s Pilgrimage: Canto the Third LXX V

The history of geography is a fascinating topic. The subject in its literal translation is writing about the earth. It is a long and sustained account of the world we live in and gives an historical depth and resonance to our understanding of contemporary environmental concerns and issues.

The dominant mode of situating this writing has a triumphalist feeling; how we used to be ignorant but are now much more enlightened. In more recent years a more knowing, post-modern narrative has focused on competing ideologies, contested accounts and argumentative conversations.1 Even here, however, the framing of the debates is still from a centred present that indicates an enlightenment teleology. In recent years I have begun to look again at the intellectual traditions of geography. This re-examination is part of a broader attempt to excavate past representations of the world for the insights they shed on understanding contemporary issues. My reworking is concerned with identifying what has been shed over the years rather than what has been accumulated. I am less interested in what we have come to know and more concerned with what we have come to forget.

The basic argument of this chapter is that older, pre-modern geographies encompassed a wider arc. They provided a cosmography. Modern geographies, especially in the last two centuries, have privileged certain areas and ignored others. The arc has been narrowed. Cosmography has been replaced by geography. The narrowing is not innocent of wider implications concerning our use of the earth and the sense of ourselves.

Ptolemy’s cosmography

One of the earliest geographers was a man called Claudius Ptolemy. He was a Greek-Egyptian who worked in the great library of Alexandria in the second century after the birth of Christ.

A personal note: the first essay I can remember writing as an undergraduate was on Claudius Ptolemy. I did some general reading and wrote about his world map, a cartographic legacy from the ancient world to the Renaissance. I described the achievement of plotting latitude and longitude in mapping the world. I did not do extensive reading; it was an essay written between other projects, some academic, most not. But I did get the general picture of a forerunner of our contemporary view of the world. Ptolemy had given us a map of the world, the earth plotted and gridded.

Later, much later, I discovered that Ptolemy had another life. He was not only a geographer and mapmaker but an astrologer and cosmologist. The general picture of Ptolemy outlined to geography undergraduates, then as now, ignored the other Ptolemy, the Ptolemy who seemed to be out of step with the scientific project. In my first essay I looked at Ptolemy as a forerunner of a scientific method. In this chapter, written 2 5 years after the first, I want to look at this other Ptolemy, the forerunner of alternative geographies.

We know very little about Ptolemy the man. He lived sometime between AD 127 and 145. Where he was born, what he looked like and his exact connection to the work that bears his name are not fully known. There is ample space for conjecture and fancy. The changing descriptions of the man tell us more about the observer than the observed.

We know a bit more of where he lived. He spent his adult life in Alexandria, a Greek city founded in 331 BC and named after Alexander the Great. One of Alexander’s generals made himself ruler, called himself Ptolemy and created a dynasty over what is now Egypt that lasted seven generations until Cleopatra. It was an empire centred in Alexandria. The city was one of the wonders of the classical world, competing with Rome and Constantinople for size and grandeur. The city grew to almost half a million; it was a major trading centre, the giant lighthouse forming a beacon to the many ships plying their trade around the Mediterranean and beyond, bringing tin from Britain, silk from China and cotton from India. There were palaces and large public buildings, including assembly halls, gymnasiums and bath houses. At the heart of the intellectual life of the city was the great library. The early Ptolemies, especially Ptolemy I (366-283 BC) and Ptolemy II (308-246 BC), established a museum and library that eventually held over 700,000 volumes. The great library was a major centre of scholarship: manuscripts were copied and the Alexandrian editions became the standard editions and dictionaries were constructed as were rules of grammar. Much of Greek and indeed Babylonian learning was transcribed, discussed, amended, systematized and improved. Euclid and Archimedes worked at the library, and Eratosthenes (276—194 BC) was, for a time, the chief librarian. Ptolemy was able to draw upon a vast pool of classical learning. For a scholar and a writer there was no better place to be in the world.

A word of caution about when we use the term Ptolemy. He is not a writer whose works have come down to us untouched from the original starting point of Alexandria. His work was translated into Arabic from Greek, and from Arabic and Greek into Latin and then from Latin into many other languages. But they were not just acts of translation; there was a creative editing and compilation, additions and subtractions. When we use the term Ptolemy we are really referring to a creative transmission belt of many hands that has added things to the ‘original’ message. Ptolemy’s name covers the work of a variety of scholars, some known, many unknown.

Ptolemy wrote on astronomy, astrology, geography, mathematics, optics and music. I will limit my comments to the first three since they form a coherent cosmology.

The Almagest is his earliest major work. The title comes from the Arabic for ‘great compilation’; the original Greek title was ‘astronomical compilation’, but it later came to be known as the ‘great compilation’ or ‘great work’. In this 13-volume encyclopedia, Ptolemy brought together existing Greek knowledge into a systematized whole and gave it a distinctive coherence. Book 1 outlines a planetary model of a stationary spherical earth around which the fixed stars revolve from east to west. Ptolemy develops a trigonometry that allows him to examine the annual variation in solar declination. Book 2 provides a table of rising time at various latitudes. This knowledge is an essential astrological requirement for horoscopes. Book 3 provides estimates of the length of the year. Ptolemy Books 4 and 5 deal with the moon and plot its movement across the night sky. Book 6 discusses solar and lunar eclipses, and Books 7 and 8 fixed stars. In the latter two, Ptolemy provides tables of the latitude and longitude of over a thousand stars. Books 9-13, which deal with the planets, are where he adopts the order, now traditionally used, of Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn.

The Almagest draws upon previous work, especially Hipparchus, which Ptolemy freely admits, but Ptolemy provided the first systematic account, some original observations and an underlying theory. Although some of the calculations have been shown to be faulty, even by the standards of the classical world, even a modern critic could note, ‘the Almagest is a masterpiece of clarity and method, superior to any scientific textbook and with few peers from any period’.2 It is an original piece of work that maps the heavens. In an elegant trigonometric formulation Ptolemy plots the location of the sun, moon, stars and planets and their trajectory across the sky.

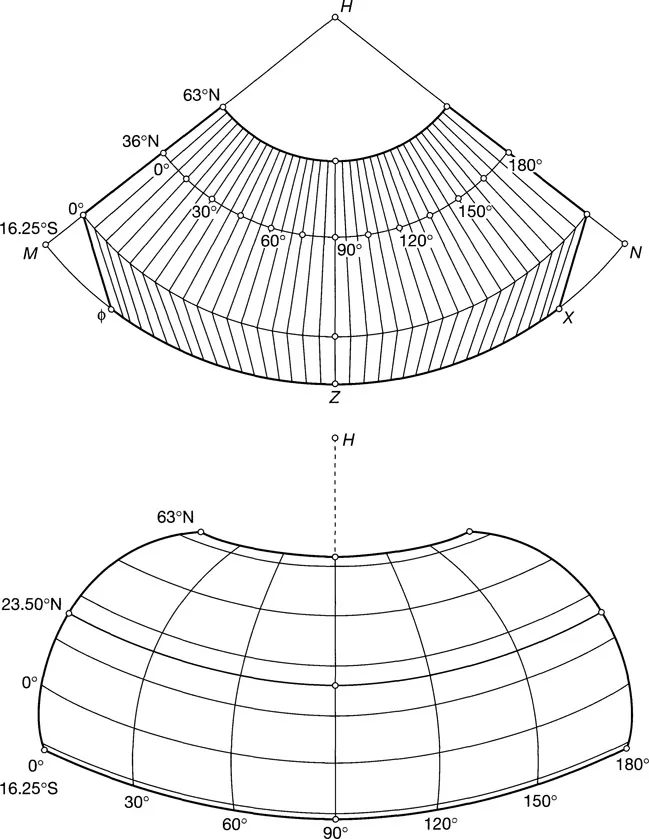

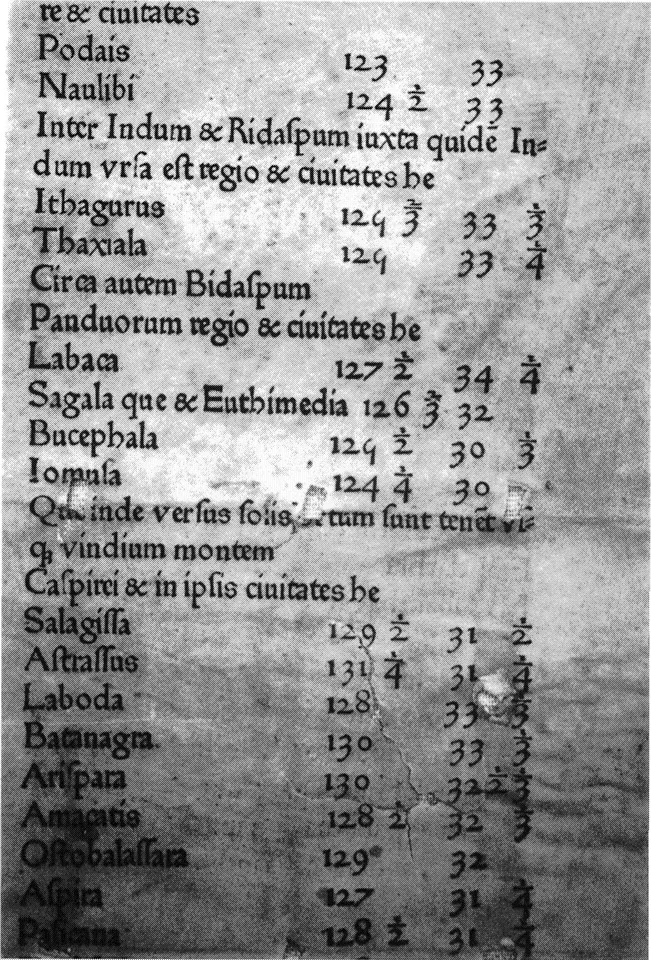

If the Almagest plotted the celestial universe, then his Geography sought to map the terrestrial world. In this text Ptolemy begins by making a distinction between chorography and geography. Chorography is the study of individual places while geography is ‘a representation in picture of the whole world together with the phenomena which are contained therein’.3 Book 1 of Geography defines latitude and longitude, discusses methods of mapmaking and poses the problem of how to represent the round world on a flat surface. He proposes two map projections, a conic projection, and a partial conic projection, on which to represent the habitable world (Figure 1.1). Books 2-7 are a gazetteer that lists the latitude and longitude of places in the known world (Figure 1.2). His work was probably accompanied by maps: Book 8 discusses the maps of particular regions of the earth, ten for Europe, four for Africa and twelve for Asia, but these have not survived. Ptolemy, however, provided the map projection and the raw latitude and longitude data that allowed places to be located on a map. Ptolemy provided a code that could be used by others to construct maps of the world.

He also divided the world into climatic zones of torrid, temperate and freezing based on the angle of sun. The terms inclination, climate and angle share a similar etymological basis. His most famous ‘mistake’ was to underestimate the size of the world: Ptolemy’s estimates were the ones used by Columbus to justify the relative ease of travelling to China.

Figure 1.1 Ptolemy’s map projections.

Ptolemy is often seen in traditional accounts as the ‘father’ of geography (a name I always consider absurd since procreation involves a mother, a figure never mentioned in the traditional narratives). He recorded information on much of the known world, and presented the mathematical outlines of a map of the world. He was one of the first to write of parallels of latitude and meridians of longitude. His method of using grids of lines of latitude and longitude to fix location is still used today. As in the Almagest, his Geography was concerned to use mathematics to plot and grid the world.

Figure 1.2 Latitude and longitude in Ptolemy’s ‘Geography’. (From a 1482 manuscript in the Library of Congress.)

Ptolemy looked at the stars as well as the earth. To describe his work the term cosmography is appropriate, a Greek word that means order, the opposite of chaos. For Ptolemy, the universe - the earth and the sky - was a unitary system. The terrestrial and the celestial were part of a broader whole that connected people to their environment in all kinds of subtle and profound ways. Even the lines of latitude and longitude used to fix locations on earth were parallels of imaginary lines across the celestial heavens. The gazetteer that he developed to fix the location of places on earth by lines of latitude and longitude was initially intended to give a fix on the stars of the firmament.

Ptolemy was also an astrologist. His Tetrabiblos was an extended astrological treatise. At that time, there was no distinction between astrology and astronomy. Mathematics, geometry and astrology formed more of a coherent whole than they do today. The study of the stars assumed that there was a causal connection between planetary movements on the one hand and human action and behaviour on the other. The universe was studied for intimations of cosmic influence, and human understanding of the world was bound up with a sense of connection between the internal world of human psychology and temperament, and the external world of planetary alignment.

The Tetrabiblos, as the name suggests, has four parts. In the introduction to Book 1 Ptolemy makes a distinction between what we would now call astronomy and astrology. The former looks at the relationship between sun, moon and stars; the latter examines the effects of these celestia...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- CONTENTS

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS COPY

- Figures

- Introduction

- 1. From Cosmography to Geography

- 2. A Heart-shaped World?

- 3. Ancient Geographies

- 4. The Speaking Land

- 5. Postscript: Alternative Geographies, New Cosmologies

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Alternative Geographies by John Rennie Short,John R. Short in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.