eBook - ePub

Contributions To Information Integration Theory

Volume 3: Developmental

- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The theory of information integration provides a unified, general approach to the three disciplines of cognitive, social, and developmental psychology. Each of these volumes illustrates how the concepts and methods of this experimentally-grounded theory may be productively applied to core problems in one of these three disciplines.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Contributions To Information Integration Theory by Norman H. Anderson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Developmental Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Adaptive Thinking in Intuitive Physics

Preface

In the functional perspective, thought and action are purposive, goal directed. The function of knowledge lies in pursuit of goals. But goals are ever changing, a consequence of ever changing motivation and environment. Effective thinking thus needs to be adaptive thinking.

Such a functional perspective is integral to the theory of information integration. Knowledge is considered as organized systems, both in general functional memory and in active operating memory. Operating memory, which embodies on-line thought and action in any task, is typically assembled across diverse levels and domains of knowledge. In this assemblage approach, thought and action are complex dynamic constructions.

In developmental psychology, this theoretical view has been effective and productive. Concrete contributions are illustrated in the discussions of concepts of time and speed with which this chapter begins; further work is presented in the chapter following. The conceptual usefulness of this functional, assemblage perspective is visible in these empirical applications.

Assemblage theory is an antithesis to stage theory. Stage theory considers all thinking to have the same nature or quality within any stage of development. Assemblage theory considers that all earlier so-called stages are typically coactive in thinking.

Assemblage theory takes a nonunitary approach to concepts. In the prevailing view, a concept is a well-defined entity, a view embodied in the pervasive concern with the ages at which various concepts first emerge. In the functional view, in contrast, development of concepts exhibits continual expansion, ramification, and interlocking with other abilities and knowledge. To seek to study a concept by itself is often a mistake; it cannot generally be separated from interlocking knowledge systems that support its functioning.

Assemblage theory leads similarly to new outlooks on the competence-performance distinction, which is seen as simplistic; on simplification strategy, which reifies concepts as unitary entities; and on transfer, which is considered fundamental, the essence of purposive behavior.

The domain of intuitive physics is ideal for further study of assemblage theory. The present chapter, although calling for complete departure from Piaget’s attempts at theory construction, is properly dedicated to his historical landmark contribution of empirical observations.

This chapter applies a functional perspective to the development of knowledge about the physical world. Thought and action are typically purposive, and the function of knowledge is to assist in goal attainment. Function exerts strong constraints on structure throughout the course of development. The nature of knowledge, accordingly, is most appropriately studied in the context of goal-oriented activity.

Goals, however, are ever changing, for they depend on changing motivational states and on variable situational constraints. Because goals are variable, previous learning does not generally transfer in any direct way. Each new situation requires some new selection and integration of previous knowledge and present information. Knowledge systems need to be responsive to situational constraints. Capabilities for adapting previous experience are as important as the previous experience itself. Goal-oriented thought and action, accordingly, may appropriately be considered in a functional perspective of problem solving and adaptive thinking.

Few would disagree in principle with this functional perspective. It disagrees, however, with the predominant orientation in developmental studies of concepts about the physical world, that is, the intuitive physics of force, mass, time, and so on. The predominant orientation treats development of such psycho-physical concepts by reference to a presumed adult form that mirrors the physical world. This orientation pervades current conceptual formulations. It has determined the scope and direction of experimental analysis. Standard experimental paradigms and procedures, as a consequence, are largely blind to the functional perspective.

The purpose of this chapter is to illustrate a functional paradigm for developmental analysis of intuitive physics. The two concepts of time and speed will be examined in some detail in order to set out the characteristics of this paradigm. The final section will present a more general discussion of the functional perspective, especially in relation to adaptive thinking and assemblage theory.

Time

Applications of information integration theory embody a functional approach to developmental analysis of time concepts. This work began by considering the well-known writings of Piaget, but soon led to a quite different theoretical outlook.

Piaget’s Theory

Piaget’s View of Time. Piaget’s central thesis was that the concept of time is derived from more basic concepts of speed and distance: “The primitive concepts are, in fact, distance and velocity and that it is time which is gradually derived from them [Piaget, 1969, p. 40].” This view was reaffirmed in later work: “Psychologically, time itself appears as a relation (between space traveled and speed or between the work accomplished and power ...), that is, as a coordination of speeds [Piaget, 1971, pp. 111-112].” “Speed is therefore initially independent of duration. On the other hand, any duration supposes at any age a speed component... [pp. 14-15].” Young children, on this view, cannot have a concept of time independent of speed and distance. Even after they acquire the concepts of speed and distance, they must still acquire the operations necessary for deriving time.

The empirical ground for this view rests on Piagetian choice tasks. In the prototypical task, two trains run on parallel tracks, covering the same or different distances with same or different speeds. Subjects judge which train ran for the longer time or if the times were equal. Similar questions may be asked about speed and distance.

In this choice task, correct judgments develop later for time than for speed and distance. Younger children judge on the basis of spatial cues alone. In the first stage, children say that the train that stopped farther ahead took more time, even when it took less time by virtue of greater speed. In the second stage, speed may also affect judgment, but erroneously, for children may judge one of two equal durations to be greater if the train went slower. From many such interrelated experiments, Piaget concluded that speed and distance are the primitive concepts and that time is derived from them.

Followup Work. Most followup work has supported Piaget (e.g., Acredolo & Schmid, 1981; Richards, 1982; Siegler & Richards, 1979; Weinreb & Brainerd, 1975), not only on duration, but also on associated judgments of distance and speed. The only substantial departure from Piaget’s findings was that the concept of time may be mastered even later than Piaget had thought (Siegler & Richards, 1979).

The study by Siegler and Richards has special interest, for it used Siegler’s (1976, 1981) choice task method, which does not require verbal explanations. The first developmental rule obtained with this method was a stopping point rule, in agreement with Piaget. Also supporting Piaget, correct judgments were found to develop later for time than for speed or distance. Even 11-year-olds were seriously deficient in duration judgments.

All this work, unfortunately, is vitiated by peculiarities of the choice task introduced by Piaget and used in the followup work. Far from elucidating the development of the concept of duration, Piaget’s task obscures it. This was shown in the integration tasks illustrated in the next section.

Integration Experiments

A Study of Integration Rules. A new approach to the study of time judgments was developed by Wilkening (1981, 1982), using an integration paradigm. Subjects made judgments about an animal fleeing over a footbridge from a barking dog. The three variables were time (how long the dog barked), distance (how far the animal fled), and speed (fleetness of the animal, represented by pictures of snail, turtle, cat, etc.). Wilkening presented paired values of two variables, and subjects made quantitative judgments of the third.

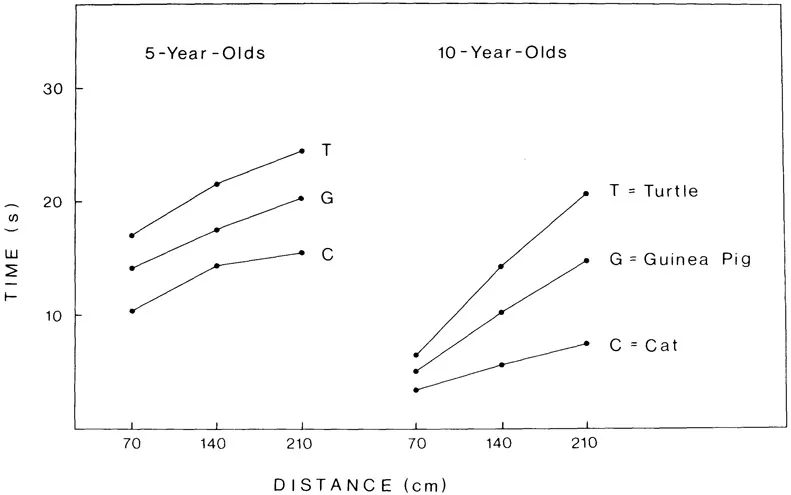

The most important result, for present illustration, was that 5-year-olds followed a subtraction rule for judgments of duration (made by turning on a record of a barking dog for the desired time), given the identity (speed) of the animal and the distance it had run. The factorial plot of these duration judgments exhibited parallelism, as shown in the left panel of Figure 1. This parallelism is prima facie evidence for the cognitive algebra,

This remarkable result simultaneously demonstrates functional understanding of all three concepts at 5 years of age.

A more radical transformation of previous ideas about development of time-speed concepts is hard to imagine. It is worth itemizing the implications of this integration rule.

First, the children had conceptual understanding of each of the three separate variables. This understanding is explicit in the algebraic relationship among the three variables. A time concept, in particular, is already present by 5 years, far earlier than recognized by Piaget.

Second, these concepts are metric. The subjective metric for each concept is present in the child’s cognition and can be scaled with functional measurement. According to Piaget, metric concepts can only appear in the stage of formal operations; integration analysis shows them present in good form in the so-called preoperational years.

Third, the three concepts are interrelated according to a sensible, though non-normative algebraic rule. The three concepts are thus operational in a practical sense, and indeed in a formal sense as well. In short, elucidation of the integration rule reveals a knowledge system entirely different from that envisaged by Piaget.

Figure 1. Judgments of time required by turtle, guinea pig, and cat to run 70, 140, or 210 cm. Judgments made by producing an actual duration of a barking dog record. Parallelism in left panel shows that 5-year-olds follow the subtraction rule, Time = Distance – Speed. Linear fan in right panel shows that 10-year-olds follow the normative division rule, Time = Distance + Speed. (After Wilkening, 1982.)

Knowledge Assessment. Why did the Piagetian choice task fail to detect the knowledge structures revealed by the integration studies? One reason is that choice involves comparisons that focus attention on single stimulus dimensions (Wilkening & Anderson, 1982, p. 235). Most experiments have included choices in which the two alternatives are equal on all but one dimension. The sensible strategy is then to cancel and ignore the equal dimensions and choose on the basis of the one unequal dimension. This strategy of ignoring all but one dimension could readily generalize to other choices as well (see Levin, Gilat, & Zelniker, 1980). The one-dimensional rules claimed by Piaget and by Siegler may thus be task-specific, not valid measures of conceptual knowledge as they believed,

A second reason is that Siegler’s methodology is prone to false successes, claiming to find rules that are not really there (see Wilkening, 1988; Wilkening & Anderson, this volume, Chapter 2). The advantage of functional measurement methodology may be seen by comparing Wilkening’s results with those of Siegler and Richards. Both studies used all three associated tasks, obtaining judgments of speed and distance as well as of time. But Siegler’s method led to the conclusion that even 11-year-olds lacked functional understanding of time, whereas Wilkening demonstrated such understanding in 5-year-olds. Also, Siegler’s method led to the conclusion that adults used the normative division rule, Speed = Distance + Time, whereas Wilkening showed they actually followed the subtracting rule, Speed = Distance - Time. And, more generally, Siegler’s method led to the conclusion that children of all ages generally failed to integrate, whereas Wilkening found well-developed integration rules already at 5 years of age. Siegler’s method thus failed badly.

Integration Choice Task. A new approach to choice was employed by Levin, Wilkening, and Dembo (1984), who used a functional measurement choice task. Piaget’s trains were replaced by faucets, each of which poured water into a hidden vessel for specified times. The child was to decide which, if either, vessel had received less water and to equalize them by running more water into the lesser vessel. By including this numerical adjustment response, decision rules for individual subjects could be diagnosed with functional measurement.

Two kinds of rules were found, metric in the older children, largely nonmetric in younger children. Almost all 13-year-olds and most 10-year-olds followed the normative physical rule, adding an amount of water proportional to the difference in flow times for the two faucets. This rule was typically mediated by a counting process: Subjects counted from the first start to the second start; fell silent while both faucets were running; made a second count from the first stop to the second stop; added or subtracted the two counts; and used this latter count for the equalization response. These children exhibited ingenious adaptive thinking.

Younger children, in contrast, exhibited a progression of four qualitative, nonalgebraic rules based on start and stop times. Rule 1 subjects chose the later stop time and were unaffected by start times. Rule 2 subjects advanced to take account of start times in the case of equal stop times. Neither rule involved any quantification, however, as shown by the random character of the adjustments, which were unrelated to the actual times.

The first hint of quantification appeared in Rule 3 subjects, who made greater adjustments for unequal stop times than for unequal start times. As with the previous rules, however, the adjustments were random, unrelated to the actual times. Finally, Rule 4 subjects showed the beginnings of true quantification, for their adjustments of cases that differed only in stop time varied directly with the difference between stop times.

The power of functional measurement appears in several ways in these rule diagnoses. The choice by itself is inadequate to assess early quantification of time. The adjustment response is almost essential for this purpose and far more efficient than choice data. Furthermore, this approach provides a proper test of goodness of fit that keeps false successes under control.

These nonalgebraic rules are similar to the kinds of rules hypothesized by Piaget and by Siegler. Their choice data, however, are inadequate evidence for such rules. Functional measurement methodology can provide valid tests for these and other such nonalgebraic rules (Wilkening & Anderson, 1982; this volume, Chapter 2). Functio...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- CHAPTER CONTENTS

- Dedication

- PREFACE

- Chapter 1. ADAPTIVE THINKING IN INTUITIVE PHYSICS

- Chapter 2. REPRESENTATION AND DIAGNOSIS OF KNOWLEDGE STRUCTURES IN DEVELOPMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY

- Chapter 3. PROBABILITY DEVELOPMENT

- Chapter 4. DEVELOPMENTAL STUDY OF PERSONAL PROBABILITY

- Chapter 5. MORAL-SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT

- Chapter 6. FAMILY LIFE AND PERSONAL DESIGN

- INDEX TO VOLUME III